Authors: SCIRE Community Team | Reviewer: Bonnie Nybo | Published: 20 March 2018 | Updated: 23 October 2024

Changes to bowel function are common after spinal cord injury (SCI). This page provides an overview of bowel changes and basic bowel care after SCI.

Key Points

- Most people experience changes to bowel function after SCI, which can affect their ability to sense bowel fullness, move stool through the bowel, and control emptying.

- These changes can lead to constipation, inability to pass stools, and leaking or accidents (incontinence), which can have a major impact on health and well-being after SCI.

- There are two main types of bowel changes after SCI:

• Spastic bowel (reflex bowel) occurs with injuries at T12 and above and involves intact bowel reflexes and tight anal sphincters.

• Flaccid bowel (non-reflex bowel) occurs with injuries below T12 and involves loss of bowel reflexes and relaxed anal sphincters.

- Bowel care typically involves following a regular bowel routine of techniques like diet and lifestyle changes, hands-on emptying techniques, and medications to empty the bowel and prevent complications.

- If a bowel routine alone is not effective, more invasive techniques like surgeries may be considered.

To better understand how bowel function changes after a spinal cord injury, it is helpful to first understand how the bowel works when the spinal cord is not injured.

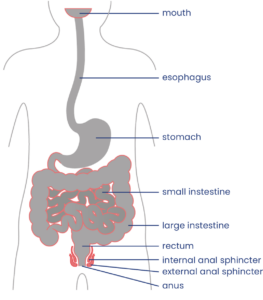

The gastrointestinal tract

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract or digestive tract) is a long tube that runs from the mouth to the anus. It is a part of the digestive system, which is responsible for extracting energy and nutrients from food and getting rid of waste.

When food is taken in through the mouth, it travels down a tube called the esophagus into the stomach, where mechanical forces and acidic stomach juices begin breaking it down. It then travels into the intestines (also called the bowel) where it is broken down further to form a stool.

The bowel

The bowel extends from the bottom of the stomach to the anus.1

The bowel (intestine or “gut”) is the segment of the gastrointestinal tract that runs from just below the stomach to the anus. It has two main parts, the small intestine and the large intestine. The bowel is where nutrients are extracted from food and indigestible waste products are formed into a stool (also called feces, pronounced “fee-sees”).

The stool is moved through the bowel by a wave-like movement of the intestinal walls called peristalsis. The last part of the bowel is called the rectum. When stool reaches the end of the bowel and stretches the walls of the rectum, signals are sent through the spinal cord to the brain, which is felt as an urge to empty.

Bowel emptying is controlled by two muscles called anal sphincters, which surround the opening of the anus:

• The internal anal sphincter is smooth muscle that is controlled automatically by a reflex.

• The external anal sphincter is skeletal muscle that is controlled consciously by the brain.

These muscles tighten to close the anus and “hold in” stool and relax to allow the bowel to empty.

The pelvic area also has pelvic floor muscles, which are a group of muscles that support the internal organs from below. These muscles also help to control bowel movements by contracting and relaxing in a coordinated fashion.

Bowel function

Part of bowel emptying occurs because of reflexes in the spinal cord. When a large amount of stool enters the rectum, it triggers emptying reflexes in the spinal cord. However, because the brain can consciously control tightening and relaxing of the external anal sphincter, the stool can be “held” until an appropriate time.

When ready to empty the bowel, these reflexes cause the internal anal sphincter to relax so that stool can leave through the anus and triggers movement in the walls of the rectum to push the stool out.

Neurogenic Bowel

After an SCI, the nerve signals that would normally allow the brain and bowel to communicate with one another cannot get through. This can contribute to a number of bowel changes that are known as neurogenic bowel dysfunction.

Loss of bowel control

Spinal cord injury can also interrupt nerve signals travelling from the brain to the anal sphincter muscles. This can lead to a loss of the ability to control when the anal sphincters tighten or relax, which cause difficulties emptying the bowel if they remain tightened all the time (stool retention) or leaking and accidents if they relax unexpectedly. The types of changes depend on whether you have spastic bowel or flaccid bowel (see below). SCI can also cause a loss of control over the pelvic floor and abdominal muscles, which also affects bowel control.

Charlie speaks about his initial fears of having a bowel accident while living in the community.

Slow movement of stool through the bowel

After an SCI, food continues to be digested and moved through the bowel. However, this movement happens at a much slower pace because signals from the brain that help coordinate this movement are blocked by the SCI. Slow movement through the bowel means that food takes much longer to digest, which can lead to dry, hard stools and constipation.

Reduced bowel sensation

Normally, nerve signals are sent to the brain when there is a sensation that the rectum is full. When the signal are blocked by an SCI, this can reduce the ability to feel when the bowel is full or recognize other sensations from the bowel, like discomfort.

Spastic Bowel

Spastic bowel can lead to constipation because of tightened sphincter muscles.3

Spastic bowel (also called reflex bowel or upper motor neuron bowel) usually occurs when the spinal cord is injured at T12 and above. With spastic bowel, the bowel’s natural reflexes are retained, but they no longer receive control from the brain. This causes increased muscle tension in the walls of the intestines, tightening of the anal sphincter muscles, and uncontrolled reflex emptying when something is present in the rectum.

Spastic bowel is typically experienced as constipation and an inability to pass a stool (stool retention). People with spastic bowel are usually able to empty the bowel by activating the bowel reflexes. This is usually done every other day through techniques like digital stimulation or the use of suppositories.

Flaccid Bowel

Flaccid bowel leads to a loss of muscle tension, and incontinence can be experienced.4

Flaccid bowel (also called non-reflex bowel or lower motor neuron bowel) usually occurs when the spinal cord is injured below T12. Flaccid bowel involves a loss of control from the brain and a loss of bowel reflex activity. This leads to a loss of muscle tension in the walls of the intestines and the anal sphincter muscles, which causes the bowel muscles to be floppy and loose.

Flaccid bowel is typically experienced as involuntary leaking of stool (incontinence) and constipation. With flaccid bowel, the stool usually needs to be removed by manual evacuation (also called disimpaction) once or twice per day to empty the bowel.

Leaking and accidents (Fecal incontinence)

Fecal incontinence is the inability to control bowel movements, leading to involuntary loss of stool. Incontinence can range from leaking a small amount of stool to a full bowel accident.

Bowel accidents are common after SCI. Most people will experience accidents early on before bowel routines have been established. It takes time and trial and error to develop a routine that allows for consistent and effective emptying that minimizes the risk of accidents.

Constipation and stool retention

Constipation is when stools are dry and hard and take a long time to pass. Constipation is common after SCI because movement of stool through the bowel is slow, which dries out the stool. The stool may also be difficult to pass if the anal sphincter muscles do not relax enough (called stool retention).

Constipation is usually treated by making lifestyle changes, such as increasing fibre and fluid in the diet, increasing physical activity and reviewing your medications. Constipation may also be treated with medications like stool softeners and occasionally other techniques like bowel irrigation.

Constipation can be treated by increasing fluid intake and physical activity.6

Understand the side effects of constipation through Josh’s experience.

Some medications and supplements may cause constipation

Medications and supplements can sometimes cause constipation. For example, some antidepressants, antispasticity medications, pain medications and supplements may contribute to constipation. Speak to your health providers for more information about whether your medications could cause constipation.

Diarrhea

Diarrhea is a loose watery stool that happens when the stool moves too quickly through the intestines. Although most people with SCI experience slow movement through the intestines, diarrhea may happen in response to certain foods, illnesses, other bowel conditions (such as stool impaction) or as a side effect of medications. It is important to speak with your health providers to determine the cause of diarrhea if it happens.

Fecal impaction (stool impaction)

Fecal impaction (stool impaction) is when a solid bulk of stool builds up within the bowel over time and gets stuck. The stool cannot be emptied through regular emptying methods. Fecal impaction happens when a person has constipation for a long time.

Although impaction involves a stool that is stuck in the bowel, it can sometimes result in leakage of stool, which is sometimes mistaken for diarrhea. This happens because watery stool may be able to get around the impacted stool and leak from the anus.

Fecal impaction can sometimes have the same symptoms as a bowel obstruction, which is a serious condition where the bowel is blocked. It is important to speak to your health team right away if you have had constipation for a long time.

Hemorrhoids (piles)

Hemorrhoids (piles) are swollen or inflamed veins in the rectum and anus. They may be located inside or outside of the anus. Symptoms may include pain, blood or mucus in the stool, and swollen protrusions out of the anus. Hemorrhoids are usually treated with a combination of medicated creams, suppositories, and sometimes surgery.

Other related problems

Bowel changes after SCI can also lead to other problems such as loss of appetite, nausea, abdominal distension (a build-up of fluid or gas in the abdomen), ulcers, rectal fissures (cracks or breaks in the skin of the rectum), and rectal prolapse (a condition where the walls of the rectum slide out of place and can protrude out of the anus).

Bowel changes can also contribute to other medical conditions like skin breakdown, pressure wounds and autonomic dysreflexia.

The main way that bowel changes are diagnosed is through a bowel history. A bowel history typically involves several components:

- Your health providers will ask you about your medical history, symptoms, and current management.

- They will ask you about your bowel routine, such as how often you have bowel movements, how long it takes you to complete your bowel routine, and what the stool looks like.

- A physical exam, including a neurological exam and a rectal exam, will also be done. This may involve an inspection of the abdomen and rectum, feeling the muscle tone in the anal sphincter muscles, and testing your bowel reflexes.

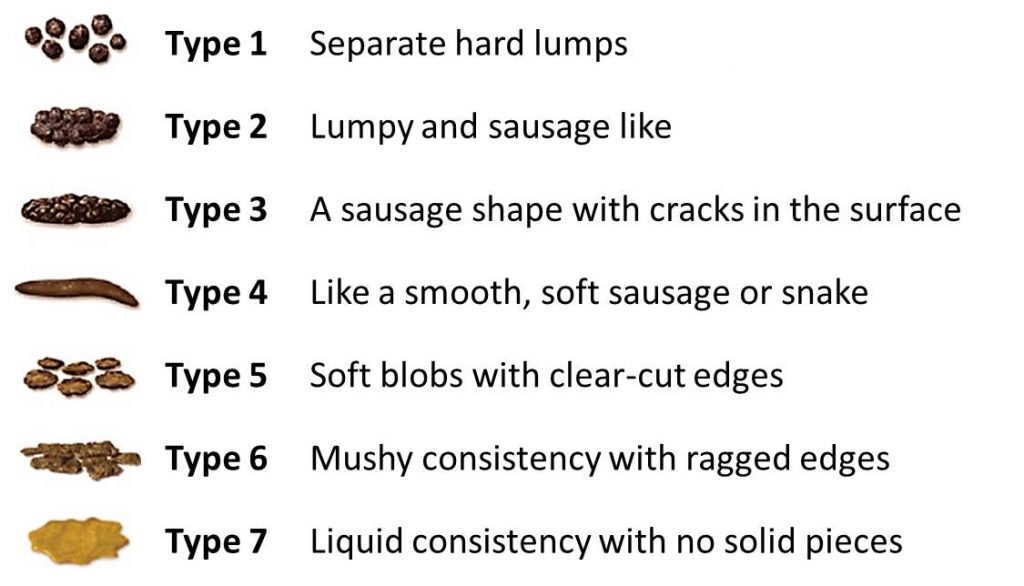

The Bristol Stool Scale

One method of communicating and keeping track of the qualities of a stool is through the use of the Bristol Stool Scale. This scale classifies stools into seven types and is a useful tool to quickly assess your stool. The goal is usually to maintain a Type 3 or Type 4 stool.

Other testing

Other testing may also be done if your health providers need further information.

- Medical imaging, such as x-ray, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen may be used for further investigation of bowel problems

- A stool sample may be taken for analysis

- Blood tests may be done to screen for infections or cancer

- A colonoscopy (the insertion of a small camera or ‘scope’ into the colon) may be done to look for colon cancer, polyps, and hemorrhoids.

A bowel review should be done regularly

Your bowel function and symptoms may change over time. Most health providers recommend people with SCI to have a check-up once every two to three years or if there are changes to bowel function to keep track of changes to your bowel function and care.

Your bowel function and symptoms may change over time. Most health providers recommend people with SCI to have a check-up once every two to three years or if there are changes to bowel function to keep track of changes to your bowel function and care.

Bowel care is an essential part of staying healthy after an SCI. For most people, a bowel routine is their main method of caring for their bowel health following SCI.

A bowel routine is a regular routine of bowel care techniques that is done every day or every other day to empty the bowel. There is a wide range of different components that may make up a bowel routine, such as hands-on emptying techniques, diet and lifestyle changes, and the use of suppositories, mini-enemas and medications.

every day or every other day to empty the bowel. There is a wide range of different components that may make up a bowel routine, such as hands-on emptying techniques, diet and lifestyle changes, and the use of suppositories, mini-enemas and medications.

Bowel routines are usually done at the same time each day, so the body gets used to the program. The goal of bowel routines is usually to be able to complete the routine within one hour on a regular basis to empty stool from the bowel and prevent accidents.

Every person’s bowel routine is different and often involves some trial and error to find the methods that best meet the person’s unique symptoms, physical abilities, preferences, and lifestyle. Although bowel routines can be complicated and time-consuming, they are a very important part of bowel care to allow for regular emptying and to prevent complications. Poorly managed bowel problems can lead to severe constipation, fecal impaction and other serious bowel complications.

Digital stimulation is a common spastic bowel emptying technique.11

Most people will need to use “hands-on” (manual) techniques to empty the bowel. Some people may need assistance from a care provider to use these techniques. They are usually done while sitting on a toilet or commode or while lying on your left side with the knees bent on an underpad.

Digital stimulation

People with spastic bowel typically use a technique called digital stimulation, digital rectal stimulation, or rectal touch to empty the bowel. Digital stimulation is a technique in which a gloved and lubricated finger (known in anatomy as a “digit”) is gently inserted into the anus and moved in circular motions along the walls of the rectum. This triggers a reflex that causes rectal contractions and loosening of the anal sphincters to allow emptying.

Digital stimulation is one of the most common techniques used for bowel emptying after SCI, however very little research has been done to determine if it is effective.

Watch for signs of autonomic dysreflexia

People with injuries at T6 and above may trigger autonomic dysreflexia when performing digital stimulation and other bowel techniques. Keep an eye out for signs including sweating, headache, heart rate changes, goose bumps and increasing muscle spasms, and stop any techniques right away. Autonomic dysreflexia can also be triggered by bowel problems such as constipation or hemorrhoids.

People with injuries at T6 and above may trigger autonomic dysreflexia when performing digital stimulation and other bowel techniques. Keep an eye out for signs including sweating, headache, heart rate changes, goose bumps and increasing muscle spasms, and stop any techniques right away. Autonomic dysreflexia can also be triggered by bowel problems such as constipation or hemorrhoids.

People who experience autonomic dysreflexia during digital stimulation may use topical anesthetic medications like Lidocaine (Xylocaine) applied to their finger to numb the nerve endings during digital stimulation. There is moderate evidence that Lidocaine helps to reduce the symptoms of autonomic dysreflexia during digital stimulation.

Refer to our article on Autonomic Dysreflexia for more information!

Manual removal of stool

People with flaccid bowel do not have bowel reflexes, so digital stimulation is not effective. Instead, the stool needs to be removed manually. This is called manual evacuation, digital disimpaction, or a rectal clear. This technique involves the use of a gloved and lubricated finger, which is inserted into the anus and used to remove stool. It may be done in conjunction with use of a lubricating suppository.

There is limited evidence that manual evacuation helps to reduce the number of bowel accidents, and it is unclear whether it helps to reduce time spent on bowel care.

Abdominal massage

Abdominal massage is a technique where a person massages the abdomen by stroking or kneading the lower torso in a clockwise motion to increase movement within the colon. However, research results on whether abdominal massage is effective for helping with bowel care after SCI have been conflicting. Use caution when using abdominal massage after a recent surgery or if you have an abdominal stoma.

Diet and fluid intake play a very important role in maintaining stools that can be moved easily through the bowel. Altering diet and fluid intake is often one of the first changes that are made to try to improve the consistency of stool and manage problems like constipation and diarrhea.

Fibre

The amount and type of fibre consumed can affect stool consistency.14

Fibre plays an important role in maintaining stool consistency so the stool can be moved easily through the bowel. Different types of fibre have different effects in the body. Soluble fibre, such as oatmeal and psyllium fibre, helps to trap waste and water along the digestive tract. It is important to increase water intake together with soluble fibre because it needs to absorb water to work. Soluble fibre may help improve stool consistency if stools are too loose or too hard. Insoluble fibre, such as whole grains, helps propel and move the contents through the colon more quickly.

There is weak evidence that diets high in fibre may actually slow down digestion after SCI. The optimal amount of fibre intake for people with SCI has not yet been studied and is highly variable between individuals, however, most health providers recommend moderate fibre intake to help with bowel care after SCI.

Refer to our article on Fibre to learn more about its role in your diet.

Fluids

Water is important to bulk up the stool to allow it to move more easily. Health providers often recommend drinking at least 2 litres of healthy fluid per day, however, the optimal amount of fluids for improving bowel movement after SCI has not yet been studied.

It may take trial and error to find the right amount of fibre and fluid

The amount of fibre and fluids for optimal bowel function is different for everyone. It usually takes some trial and error to find the right amount of fibre for you. Keeping track of your fibre and fluid intake over a period of time can be helpful in figuring out how much you need to maintain your desired stool consistency. Fibre intake should be gradually adjusted to achieve the desired consistency of stool. Speak to your health providers for more information.

Foods contributing to other symptoms

Some people find that certain foods and drinks affect their bowel function in different ways. For example, some foods may cause loose stools or constipation. Every person is different, and it may take some trial and error to find the best diet for you.

Timing of food and drink

The gastrocolic reflex is when food or drink in the stomach triggers movement in the bowel. Some people eat food or drink warm fluids at least 30 minutes before their bowel routine to try to take advantage of this reflex, which is thought to be strongest in the morning. Many people use this technique as part of their bowel care; however the evidence is conflicting about whether the gastrocolic reflex is effective after SCI.

The gastrocolic reflex is when food or drink in the stomach triggers movement in the bowel. Some people eat food or drink warm fluids at least 30 minutes before their bowel routine to try to take advantage of this reflex, which is thought to be strongest in the morning. Many people use this technique as part of their bowel care; however the evidence is conflicting about whether the gastrocolic reflex is effective after SCI.

Find out how Charlie manages his fiber and fluid intake depending on the season.

Medications and suppositories may be added to your bowel routine if hands-on techniques and diet changes are not enough.

Stool softeners

Stool softeners are a type of laxative that increases the moisture in the stool to make it easier to pass. Stool softeners are usually taken once or twice per day or as needed. Some common stool softeners include Polyethylene glycol 3350 (PEG) and Docusate sodium (Colace).

Suppositories and Micro-enemas

A suppository is a solid (usually cone or cylinder-shaped) form of medication or other substance that is inserted into the rectum to absorb. Suppositories must make contact with the bowel walls to work, so care should be taken that they are not placed into a stool.

Alternatively, a micro-enema is a liquid form of a drug administered into the rectum before a planned emptying. These methods are used to allow for quick and direct action on the bowel walls.

Stimulant laxatives (including Stimulant suppositories)

Micro-enemas are administered into the rectum before a planned emptying.18

Stimulant laxatives increase the movements in the intestinal wall that help move the stool along. There are many different stimulant laxatives that may be taken by mouth or as a suppository or micro-enema. Some common stimulant laxatives include Bisacodyl (Dulcolax) suppositories and Sennosides (Senokot).

Stimulant suppositories contain medications (such as Dulcolax) which stimulate the bowel reflex. Suppositories are usually inserted 15 to 30 minutes before planned bowel emptying. However, the medication used and even the base that the medication is dissolved in can affect how quickly the medication is absorbed. For example, Dulcolax in a water-soluble polyethylene glycol base (such as a Magic Bullet) allows shorter times to emptying than Dulcolax in a vegetable oil base.

Lubricating suppositories

Lubricating suppositories contain non-medicated substances (such as glycerin) which holds water in the bowel to make the stool softer so it is easier to pass.

Prokinetic agents

Similar to stimulant laxatives, prokinetic agents are medications that increase digestive tract muscle activity to move the stool through digestion. However, prokinetic agents also speed up movement through the upper digestive tract as well as the bowel. Prokinetic agents are not routinely used and considered as a last resort for constipation or in preparation for a bowel procedure, such as a colonoscopy.

There is moderate evidence that the prokinetic agents fampridine, neostigmine, and metoclopramide help provide relief from constipation in people with SCI. There is also some evidence that prucalopride can help SCI individuals with impaired bowel emptying but may cause abdominal pain.

Standing and Exercise

Standing and exercise have long been thought to assist with bowel management after SCI. Standing and exercise are thought to help move abdominal contents toward the rectum. However, there is not enough evidence at this time to determine whether standing and exercise are effective to help with managing bowel changes after SCI.

Assistive devices

A number of devices also exist to help with bowel management. These devices are typically used together with regular bowel care techniques, and may include:

- Commodes, raised or padded toilet seat, or automated toilet seat

- Suppository inserter or digital stimulator

- Mirrors

- Anal plugs

- Footstools

- Bowel irrigation systems

However, limited research has been done on assistive devices for bowel care, so we do not yet know if these treatments are useful to help manage bowel changes after SCI.

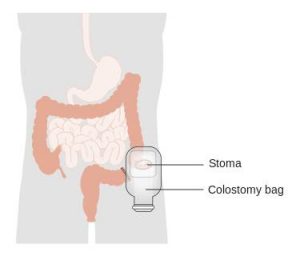

Colostomy and ileostomy surgery

Most people are able to manage their bowel function effectively with a bowel routine made up of conservative techniques and medications. However, some people may require the use of additional treatments to achieve optimal bowel care.

Colostomy and ileostomy are surgical procedures that may be used if conservative techniques do not work well or as a way to streamline bowel care. Both of these procedures involve a surgically-created hole between the intestine and the outside of the abdomen. Once the opening is formed, a pouch (collection bag) is attached to allow stool to be collected outside of the body, bypassing the rectum and anus entirely.

A colostomy is when the hole (or stoma) is created between the colon (large intestine) and the outside of the body. An ileostomy is when the hole is created between the ileum (last part of the small intestine) and the outside of the body.

A colostomy is a surgically created opening between the large intestine (colon) and an external collection device (colostomy bag).19

Although these types of surgeries are invasive, a number of different studies have shown that there are many benefits for bowel care. There is weak evidence that colostomy surgery:

- Simplifies bowel routines and reduces the amount of time spent on bowel care

- Reduces the need for use of laxatives and dietary changes in bowel care

- Reduces the number of hospitalizations related to bowel problems

- Improves independence and quality of life

These studies showed that, while there were some complications related to stoma surgeries, such as opening of the surgical wound, these were uncommon, and the majority of people were satisfied with the results of their surgery.

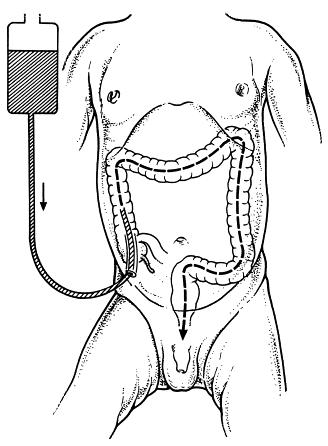

Bowel irrigation

Bowel irrigation is the use of water or other fluids (including medications) to stimulate the bowel muscles and flush stool from the bowel. This is done to help loosen stools and treat constipation. Bowel irrigation is sometimes referred to as an enema, although it typically uses more fluid than an enema. The fluid may be introduced into the bowel through the anus (called transanal irrigation) or through a surgically created stoma (called antegrade irrigation).

In MACE, the appendix is made into a stoma.20

Transanal irrigation is done through a catheter that is inserted into the rectum through the anus. The catheter may be surrounded by a balloon that can be inflated to hold the catheter in place and prevent leaking of water. The catheter is connected by a tube to a hand pump or electrical pump system to push water into the bowel. Pulsed water transanal irrigation involves quick pulses of water into the rectum to help loosen stools. There is weak evidence that transanal irrigation and pulsed water transanal irrigation helps improve bowel function after SCI.

When fluid is introduced through a stoma (antegrade irrigation), it is usually done through a small stoma into the beginning of the large intestine (the cecum) called a cecostomy or as part of a surgical technique called the Malone Antegrade Continence Enema (MACE) procedure, where the appendix is made into a stoma. Irrigation is not usually done through an ileostomy because this can cause dehydration. There are several studies which provide weak evidence that MACE is a safe and useful alternative for bowel irrigation after SCI.

Electrical and magnetic stimulation treatments (not in regular use)

Electrical and magnetic stimulation techniques are available to assist with bowel care. However, these treatments are not usually available in most healthcare settings.

Functional magnetic stimulation

Functional magnetic stimulation is a non-invasive procedure in which a magnet is placed over the spinal cord to administer magnetic waves which can stimulate nerve cells to fire. There is weak evidence that functional magnetic stimulation help improve bowel transit time after SCI.

Abdominal muscle stimulation

Abdominal muscle stimulation is another non-invasive procedure in which electrodes are placed on the abdominal muscles to stimulated muscle activity. It has been proposed that activating the abdominal muscles might help to increase pressure within the abdominal cavity, which may assist with bowel emptying for people who do not have abdominal control (injuries above T7).

Sacral anterior root stimulation

Sacral anterior root stimulation is an invasive procedure in which electrodes and a controlling device are implanted onto the sacral nerves during surgery. The device is controlled by an external transmitter and can stimulate the nerves which help empty the bowel.

There is moderate evidence that sacral anterior root stimulation may help improve constipation after SCI. Sacral root stimulation is an emerging area of research and further research in the future may provide more information about whether this treatment works.

Watch SCIRE’s video to learn more about bowel management as you age.21

All people age, and as they do they may notice changes in how they digest certain foods or that they need to go to the bathroom more frequently, or they may not go to the bathroom as successfully. As the body ages, nerve signals to the bowel may decrease and weaken bowel contractions and cause stool to move more slowly through the bowel. As a result, more water gets reabsorbed from the stool which often leads to more constipation. Some may experience more stool leaking.

Aging with SCI

For people aging with SCI, the changes in the bowel from typical aging may combine with the effects of neurogenic bowel dysfunction to worsen problems like constipation. Generally, as people age with SCI, symptoms of constipation increase, the frequency of bowel movements decrease, and the time required to complete a bowel movement increases. Medications and antibiotics taken to treat infections can also have significant effects on bowel function. They can increase constipation, increase leaks/accidents, or make the bowels less predictable.

Bowel changes that people aging with SCI may experience:

- More severe constipation

- More leakage/accidents

- Longer time spent on bowel routines

- Greater risk of pressure injuries from sitting on the toilet for longer

- Hemorrhoids

- Rectal fissures

- Bleeding from the rectum

Other aging-related problems like pain, osteoarthritis, decreased strength and mobility, and skin issues, can affect the ability to carry out bowel routines. Bowel changes like constipation, hemorrhoids, and spending more time sitting on the toilet can trigger pain, spasticity, and autonomic dysreflexia. All these changes from aging could lead to a need to reassess bowel management strategies.

Refer to the “What bowel problems can happen after SCI?” section above for more information on bowel complications.

Managing bowel changes with age

To manage changes to bowel function from aging with SCI, consult regularly with a health care provider about your bowel management. Strategies to manage bowel changes may include:

- Modifying your diet and fluid intake

- Medications for bowel movements like suppositories and laxatives

- Surgical procedures

- Reviewing your current medications and supplements (some medications can cause constipation or diarrhea as a side effect)

- Reviewing toilet and transfer equipment for injury to skin and joints

- Additional caregiver help

Changing diet and water intake needs

Drinking water and the types of foods you eat both play an important part in how easily stool moves through the bowel. Needing to adjust what you eat and drink as you age is common since people often feel less appetite and thirst, and your body will not be as good at maintaining water and nutrient levels.

The optimal diet and daily water intake are different for each person, but finding the right balance can make a big difference for your bowels. You might also find that adjusting when in the day you eat and drink can affect your bowel movements.

Many people with SCI change their bowel management as they age. In one study, 63% of participants changed their bowel management methods over 20 years. People who used only medication and/or straining to manage their bowels were most likely to change their methods. Use of colostomy and bowel irrigation for management increased during this time.

For some people with long bowel routines (1-2 hours spent on bowel care per day), undergoing a colostomy was able to reduce time spent on bowel care to around 10-20 minutes per day. When considering surgical options for bowel management, people with SCI find it helpful to talk to stoma nurses, SCI doctors, and peers.

There is also research looking at the potential for nerve stimulation to improve bowel function and reduce time needed for bowel management. This may be available depending on location.

Refer to the “Diet and fluids”, “Medications and suppositories”, and “Other treatments and techniques” sections above for more information.

When do I need to review or change my bowel routine?

- Your current routine is not working anymore.

- The time and energy you spend on bowel management is limiting time spent with family/friends or doing things you love.

Questions to ask yourself to manage bowel changes

- What has changed (issues, challenges, barriers)?

- When did the change start?

- What is the root cause of the change? (medical illness, injury, surgery, mobility, weakness, cognitive changes, social changes, financial changes)

- What treatments or recommendations have been tried so far?

- What has worked and what has not?

- When was the most recent review of bowel with a family doctor or physiatrist?

- Are current care team members actively involved to provide guidance and support?

Most people experience bowel changes after SCI. Even when well managed, bowel care can take up a lot of time and energy each day, which may interfere with maintaining a regular schedule. Bowel problems can also interfere with important activities like work, socializing and sexual intimacy.

Caring for bowel changes and establishing a bowel routine after SCI is one of the highest priorities for recovery after injury. Bowel care typically involves developing a conservative bowel management routine in combination with various manual techniques, diet changes, and medications. Several other procedures exist that are not as commonly used, such as cecostomy, colostomy and ileostomy surgeries and bowel irrigation.

For a review of how we assess evidence at SCIRE Community and advice on making decisions, please see SCIRE Community Evidence.

Parts of this page have been adapted from the SCIRE Professional “Bowel Dysfunction and Management” and “Autonomic Dysreflexia” Module:

Coggrave M, Mills P, Willms R, Eng JJ, (2014). Bowel Dysfunction and Management Following Spinal Cord Injury. In Eng JJ, Teasell RW, Miller WC, Wolfe DL, Townson AF, Hsieh JTC, Connolly SJ, Noonan VK, Loh E, McIntyre A, editors. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence. Version 5.0. Vancouver: p 1- 48.

Available from: https://scireproject.com/evidence/bowel-dysfunction-and-management/

Krassioukov A, Blackmer J, Teasell RW, Eng JJ (2014). Autonomic Dysreflexia Following Spinal Cord Injury. In Eng JJ, Teasell RW, Miller WC, Wolfe DL, Townson AF, Hsieh JTC, Connolly SJ, Noonan VK, Loh E, McIntyre A, editors. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence. Version 5.0. Vancouver: p 1- 35.

Available from: https://scireproject.com/evidence/autonomic-dysreflexia/

Mortenson WB, Sakakibara BM, Miller WC, Wilms R, Hitzig S, Eng JJ (2014). Aging Following Spinal Cord Injury. In Eng JJ, Teasell RW, Miller WC, Wolfe DL, Townson AF, Hsieh JTC, Connolly SJ, Noonan VK, Loh E, McIntyre A, editors. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence. Version 5.0. Vancouver: p 1- 90.

Available from: scireproject.com/evidence/aging/

Evidence for “Hands-on bowel techniques” is based on the following studies:

[1] Sloots CE, Felt-Bersma RJ, Meuwissen SG, Kuipers EJ. Influence of gender, parity, and caloric load on gastrorectal response in healthy subjects: a barstat study. Dig Dis Sci 2003; 48: 516-521.

[2] Ford MJ, Camilleri MJ, Hanson RB, Wiste JA, Joyner MJ. Hyperventilation, central autonomic control, and colonic tone in humans. Gut 1995; 37: 499-504.

[3] Korsten M, Singal AK, Monga A, Chaparala G, Khan AM, Palmon R, Mendoza JRD, Lirio JP, Rosman AS, Spungen A, Bauman WA. Anorectal stimulation causes increased colonic motor activity in subjects with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2007; 30: 31-35.

[4] Furusawa K, Sugiyama H, Tokuhiro A, Takahashi M, Nakamura T, Tajima F. Topical anesthesia blunts the pressor response induced by bowel manipulation in subjects with cervical spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2009;47:144-148.

[5] Solomons J and Woodward S. Digital removal of faeces in the bowel management of patients with spinal cord injury: a review. British Journal of Neuroscience Nursing 2013; 9: 216-222.

[6] Menter R, Weitzenkamp D, Cooper D, Bingley J, Charlifue S, Whiteneck G. Bowel management outcomes in individuals with long-term spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord 1997; 35: 608-612.

[7] Haas U, Geng V, Evers GC, Knecht H. Bowel management in patients with spinal cord injury — a multicentre study of the German speaking society of paraplegia (DMGP). Spinal Cord. 2005; 43: 724-30.

[8] Ayas S, Leblebici B, Sozay S, Bayramoglu M, Niron EA. The effect of abdominal massage on bowel function in patients with spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2006; 85: 951-955.

[9] Hu C, Ye M, Huang Q. Effects of manual therapy on bowel function of patients with spinal cord injury. J Phys Ther Sci 2013; 25: 687-688.

Evidence for “Diet and fluids” is based on the following studies:

[1] Cameron KJ, Nyulasi IB, Collier GR, Brown DJ. Assessment of the effect of increased dietary fibre intake on bowel function in patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 1996; 34: 277-283.

Evidence for “Medications and suppositories” is based on the following studies:

Stimulant laxatives

[1] House JG, Stiens SA. Pharmacologically initiated defecation for persons with spinal cord injury: effectiveness of three agents. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1997; 78: 1062-1065.

Prokinetic agents

[1] Cardenas DD, Ditunno J, Graziani V, Jackson AB, Lammertse D, Potter P, Sipski M, Cohen R, Blight AR. Phase 2 trial of sustained-release fampridine in chronic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 158-168.

[2] Korsten MA, Rosman AS, Ng A, Cavusoglu E, Spungen AM, Radulovic M, Wecht J, Bauman WA. Infusion of neostigmine-glycopyrrolate for bowel evacuation in persons with spinal cord injury. Am J Gastroenterol 2005; 100: 1560-1565.

[3] Segal JL, Milne N, Brunnemann SR, Lyons KP. Metoclopramide-induced normalization of impaired gastric emptying in spinal cord injury. Am J Gastroenterol 1987; 82: 1143-1148.

[4] Krogh K, Jensen MB, Gandrup P, Laurberg S, Nilsson J, Kerstens R, De Pauw M. Efficacy and tolerability of prucalopride in patients with constipation due to spinal cord injury. Scand J Gastroenterol 2002; 37: 431-436.

Evidence for “Other treatments and techniques” is based on the following studies:

Assistive Devices

[1] Hoenig H, Murphy T, Galbraith J, Zolkewitz M. Case study to evaluate a standing table for managing constipation. SCI Nursing 2001;18: 74-7.

[2] Uchikawa K, Takahashi H, Deguchi G, Liu M. A washing toilet seat with a CCD camera monitor to stimulate bowel movement in patients with spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2007; 86: 200-204.

Colostomy and Ileostomy surgery

[1] Frisbie JH, Tun CG, Nguyen CH. Effect of enterostomy on quality of life in spinal cord injury patients. J Am Paraplegia Soc 1986; 9: 3-5.

[2] Stone JM, Wolfe VA, Nino-Murcia M, Perkash I. Colostomy as treatment for complications of spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil1990b; 71: 514-518.

[3] Kelly SR, Shashidharan M, Borwell B, Tromans AM, Finnis D, Grundy DJ. The role of intestinal stoma in patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 1999; 37: 211-214.

[4] Rosito O, Nino-Murcia M, Wolfe VA, Kiratli BJ, Perkash I. The effects of colostomy on the quality of life in patients with spinal cord injury: a retrospective analysis. J Spinal Cord Med 2002; 25: 174-183.

[5] Branagan G, Tromans A, Finnis D. Effect of stoma formation on bowel care and quality of life in patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2003; 41: 680-683.

[6] Munck J, Simoens Ch, Thill V, Smets D, Debergh N, Fievet F, Mendes da Costa P. Intestinal stoma in patients with spinal cord injury: a retrospective study of 23 patients. Hepatogastroenterology 2008; 55: 2125-2129.

[7] Coggrave MJ, Ingram RM, Gardner BP, Norton C. The impact of stoma for bowel management after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2012; 50: 848-852.

Bowel irrigation

[1] Del Popolo G, Mosiello G, Pilati C, Lamartina M, Battaglino F, Buffa P, Redaelli T, Lamberti G, Menarini M, Di Benedetto P, De Gennaro M. Treatment of neurogenic bowel dysfunction using transanal irrigation: a multicenter Italian study. Spinal Cord 2008; 46: 517-522.

[2] Christensen P, Kvitzau B, Krogh K, Buntzen S, Laurberg S. Neurogenic colorectal dysfunction – use of new antegrade and retrograde wash-out methods. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 255-261.

[3] Faaborg PM, Christensen P, Kvitsau B, Buntzen S, Laurberg S, Krogh K. Long-term outcome and safety of transanal colonic irrigation for neurogenic bowel dysfunction. Spinal Cord 2009; 47: 545-549.

[4] Kim HR, Lee BS, Lee JE, Shin HI. Application of transanal irrigation for patients with spinal cord injury in South Korea: a 6-month follow-up study. Spinal Cord 2013; 51: 389-394.

[5] Teichman JMH, Harris JM, Currie DM, Barber DB. Malone antegrade continence enema for adults with neurogenic bowel disease. Journal of Urology 1998; 160: 1278-1281.

[6] Christensen P, Kvitzau B, Krogh K, Buntzen S, Laurberg S. Neurogenic colorectal dysfunction – use of new antegrade and retrograde wash-out methods. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 255-261.

[7] Teichman JMH, Zabihi N, Kraus SR, Harris JM, Barber DB. Long-term results for Malone antegrade continence enema for adults with neurogenic bowel disease. Urology 2003; 61: 502-506.

[8] Worsoe J, Christensen P, Krogh K, Buntzen S, Laurberg S. Long-term results of antegrade colonic enema in adult patients: assessment of functional results. Dis Colon Rectum 2008; 51: 1523-1528.

[9] Puet TA, Jackson H, Amy S. Use of pulsed irrigation evacuation in the management of the neuropathic bowel. Spinal Cord 1997; 35: 694-699.

Electrical and magnetic stimulation

[1] Korsten MA, Fajardo NR, Rosman AS, Creasey GH, Spungen AM, Bauman WA. Difficulty with evacuation after spinal cord injury: Colonic motility during sleep and effects of abdominal wall stimulation. JRRD 2004; 41: 95-99.

[2] Tsai PY. Wang CP, Chiu FY, Tsai YA, Chang YC, Chuang TY. Efficacy of functional magnetic stimulation in neurogenic bowel dysfunction after spinal cord injury. J Rehabil Med 2009; 41: 41-47.

[3] Lin VW, Kim KH, Hsiao I, Brown W. Functional magnetic stimulation facilitates gastric emptying. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002; 83: 806-810.

[4] Lin VW, Nino-Murcia M, Frost F, Wolfe V, Hsiao I, Perkash I. Functional magnetic stimulation of the colon in persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001; 82: 167-173.

[5] Binnie NR, Smith AN, Creasey GH, Edmond P. Constipation associated with chronic spinal cord injury: the effect of pelvic parasympathetic stimulation by the Brindley stimulator. Paraplegia 1991; 29: 463-469.

Evidence for “How does aging with SCI affect the bowel?” is based on:

Britton, E., & McLaughlin, J. T. (2013). Ageing and the gut. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 72(1), 173–177. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665112002807

Cameron, K. J., Nyulasi, I. B., Collier, G. R., & Brown, D. J. (1996). Assessment of the effect of increased dietary fibre intake on bowel function in patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord, 34(5), 277–283. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.1996.50

Charlifue, S., Jha, A., & Lammertse, D. (2010). Aging with Spinal Cord Injury. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, 21(2), 383–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2009.12.002

Coggrave, M. J., Ingram, R. M., Gardner, B. P., & Norton, C. S. (2012). The impact of stoma for bowel management after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord, 50(11), 848–852. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2012.66

Fosnes, G. S., Lydersen, S., & Farup, P. G. (2011). Constipation and diarrhoea – common adverse drug reactions? A cross sectional study in the general population. BMC Clinical Pharmacology, 11(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6904-11-2

Johns, J., Krogh, K., Rodriguez, G. M., Eng, J., Haller, E., Heinen, M., Laredo, R., Longo, W., Montero-Colon, W., Wilson, C. S., & Korsten, M. (2021). Management of Neurogenic Bowel Dysfunction in Adults after Spinal Cord Injury. The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine, 44(3), 442–510. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790268.2021.1883385

Johns, J. S., Krogh, K., Ethans, K., Chi, J., Querée, M., & Eng, J. J. (2021). Pharmacological Management of Neurogenic Bowel Dysfunction after Spinal Cord Injury and Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review and Clinical Implications. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(4), 882. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10040882

Nielsen, S. D., Faaborg, P. M., Christensen, P., Krogh, K., & Finnerup, N. B. (2017). Chronic abdominal pain in long-term spinal cord injury: a follow-up study. Spinal Cord, 55(3), 290–293. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2016.124

Nielsen, S. D., Faaborg, P. M., Finnerup, N. B., Christensen, P., & Krogh, K. (2017). Ageing with neurogenic bowel dysfunction. Spinal Cord, 55(8), 769–773. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2017.22

Parittotokkaporn, S., Varghese, C., O’Grady, G., Svirskis, D., Subramanian, S., & O’Carroll, S. J. (2020). Non-invasive neuromodulation for bowel, bladder and sexual restoration following spinal cord injury: A systematic review. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery, 194, 105822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.105822

Rosito, O., Nino-Murcia, M., Wolfe, V. A., Kiratli, B. J., & Perkash, I. (2002). The Effects Of Colostomy On The Quality Of Life In Patients With Spinal Cord Injury: A Retrospective Analysis. The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine, 25(3), 174–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790268.2002.11753619

Savic, G., Frankel, H. L., Jamous, M. A., Soni, B. M., & Charlifue, S. (2018). Long-term bladder and bowel management after spinal cord injury: a 20-year longitudinal study. Spinal Cord, 56(6), 575–581. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-018-0072-4

Wahlqvist, M., & Savige, G. (2000). Interventions aimed at dietary and lifestyle changes to promote healthy aging. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 54(S3), S148–S156. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601037

Wong, S., Santullo, P., Hirani, S. P., Kumar, N., Chowdhury, J. R., García-Forcada, A., Recio, M., Paz, F., Zobina, I., Kolli, S., Kiekens, C., Draulans, N., Roels, E., Martens-Bijlsma, J., O’Driscoll, J., Jamous, A., & Saif, M. (2017). Use of antibiotics and the prevalence of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in patients with spinal cord injuries: an international, multi-centre study. Journal of Hospital Infection, 97(2), 146–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2017.06.019

Other references

Anderson KD. Targeting recovery: Priorities of the spinal cord-injured population. Journal of Neurotrauma 2004; 21: 1371-1383.[4] Badiali D, Bracci F, Castellano V, Corazziari E, Fuoco U, Habib FI, Scivoletto G. Sequential treatment of chronic constipation in paraplegic subjects. Spinal Cord 1997; 35: 116-120.

Brading AF, Ramalingam T. Mechanisms controlling normal defecation and the potential effects of spinal cord injury. Prog Brain Res 2006; 152: 345-58.

Byrne CM, Pager CK, Rex J, Roberts R, Solomon MJ (1998): Assessment of Quality of Life in the treatment of patients with neuropathic fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 2002; 45: 1431-6.

Coggrave M, Burrows D, Durand MA. Progressive protocol in the bowel management of spinal cord injuries. British Journal of Nursing 2006; 15: 1108-1113.

Coggrave M, Norton C, Cody JD. Management of fecal incontinence and constipation in adults with central neurological diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD002115.

Coggrave MJ, Norton C, Wilson-Barnett J. Management of neurogenic bowel dysfunction in the community after spinal cord injury: a postal survey in the United Kingdom. Spinal Cord 2009; 47: 323-330.

Coggrave MJ, Norton C. The need for manual evacuation and oral laxatives in the management of neurogenic bowel dysfunction after spinal cord injury: a randomized controlled trial of a stepwise protocol. Spinal Cord. 2010; 48: 504-10.

Correa GI, Rotter KP. Clinical evaluation and management of neurogenic bowel after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord2000; 38: 301-308.

Cosman BC, Vu TT. Lidocaine anal block limits autonomic dysreflexia during anorectal procedures in spinal cord injury: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1556-61.

Emmanuel A. Review of the efficacy and safety of transanal irrigation for neurogenic bowel dysfunction. Spinal Cord. 2010;48:664-73.

Faaborg PM, Christensen P, Finnerup N, Laurberg S, Krogh K. The pattern of colorectal dysfunction changes with time since spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2008; 46: 234-238.

Fajardo NR, Pasiliao RV, Modeste-Duncan R, Creasey G, Bauman WA, Korsten MA. Decreased colonic motility in persons with chronic spinal cord injury. Am J Gastroenterol 2003; 98: 128-34.

Fealey RD, Szurszewski JH, Merrit JL, DiMagno EP. Effect of traumatic spinal cord transection on human upper gastrointestinal motility and gastric emptying. Gastroenterology 1984; 87: 69-75.

Finnerup NB, Faaborg P, Krogh K, Jensen TS. Abdominal pain in long-term spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2008; 46: 198-203.

Furusawa K, Sugiyama H, Ikeda A, Tokuhiro A, Koyoshi, H, Takahashi M, Tajima F. Autonomic dysreflexia during a bowel program in patients with cervical spinal cord injury. Acta Med Okayama 2007; 61: 211-227.

Glickman S, Kamm MA. Bowel dysfunction in spinal-cord-injury patients. Lancet 1996; 347: 1651-3.

Gondim FA, Rodrigues CL, da Graça JR, Camurça FD, de Alencar HM, dos Santos AA, Rola FH. Neural mechanisms involved in the delay of gastric emptying and gastrointestinal transit of liquid after thoracic spinal cord transection in awake rats. Auton Neurosci. 2001; 87: 52-8.

Krogh K, Mosdal C, Laurberg S. Gastrointestinal and segmental colonic transit times in patients with acute and chronic spinal cord lesions. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 615-621.

Leduc BE, Spacek E, Lepage Y. Colonic transit time after spinal cord injury: any clinical significance? J Spinal Cord Med 2002; 25: 161-6.

Lynch AC, Antony A, Dobbs BR, Frizelle FA. Bowel dysfunction following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2001; 39: 193-203.

Lynch AC, Frizelle FA. Colorectal motility and defecation after spinal cord injury in humans. Prog Brain Res 2006; 152: 335-43.

Lynch AC, Wong C, Anthony A, Dobbs BR, Frizelle FA. Bowel dysfunction following spinal cord injury: a description of bowel function in a spinal cord-injured population and comparison with age and gender matched controls. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 717-723.

Menter R, Weitzenkamp D, Cooper D, Bingley J, Charlifue S, Whiteneck G. Bowel management outcomes in individuals with long-term spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord 1997; 35: 608-612.

Ng C, Prott G, Rutkowski S, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms in spinal cord injury: relationships with level of injury and psychologic factors. Dis Colon Rect 2005;48:1562-1568.

Nino-Murcia M, Stone JM, Chang PJ, Perkash I. Colonic transit in spinal cord-injured patients. Invest Radiol 1990; 25: 109-112.

Rajendran SK, Reiser JR, Bauman W, Zhang RL, Gordon SK, Korsten MA. Gastrointestinal transit after spinal cord injury: effect of cisapride. Am J Gastroenterol 1992; 87: 1614-1617.

Stiens SA, Bergman SB, Goetz LL. Neurogenic bowel dysfunction after spinal cord injury: clinical evaluation and rehabilitative management. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1997;78:S86-S102.

Stone JM, Nino-Marcia M, Wolfe VA, Perkash I. Chronic gastrointestinal problems in spinal cord injury patients: a prospective analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 1990a; 85: 1114-9.

Image credits

- The Bowel ©SCIRE, CC BY-SA 3.0

- Belly abdominal pain ©Christian Dorn, CC0 1.0

- Man toilet bathroom sitting ©Clker-Free-Vector-Images, CC0 1.0

- Leak plumbing water drips bathroom ©Clker-Free-Vector-Images, CC0 1.0

- Mistake spill slip up accident ©Steve Buissinne, CC0 1.0

- Water jump refreshment children ©AxxLC, CC0 1.0

- Image ©SCIRE, CC BY-SA 3.0

- Bristol Stool Chart ©Cabot Health, CC BY-SA 3.0

- Scientist ©H Alberto Gongora, CC BY 3.0 US

- Towel napkin dab dry vector ©Isa KARAKUS, CC0 1.0

- Modified from: Hand finger pointing ©truthseeker08, CC0 1.0

- Electricity ©Artnadhifa, CC BY 3.0 US

- Abdomen clockwise clock massage ©bodymybody, CC0 1.0

- Breads cereals oats barley wheat ©FotoshopTofs, CC0 1.0

- Scale question importance balance ©Arek Socha, CC0 1.0

- Alarm clock time of good morning ©congerdesign, CC0 1.0

- Suppositories pharmacy ©Andreas Koczwara, CC0 1.0

- Microlax Miniklistier ©MedInfo Johnson&Johnson, CC BY-SA 4.0

- Cancer Research UK (Original email from CRUK), CC BY-SA 4.0

- Reprinted with permission from Malone PSJ. Malone procedure for antegrade continence enemas. In: Spitz L, and Coran AG, eds. Rob & Smith’s Operative Surgery: Pediatric Surgery. 5th ed. London: Chapman & Hall Medical; 1995:459–467.

- Aging Bowel Thumbnail ©SCIRE, CC BY-NC 4.0

- Clock by Abu Ibrahim Icon, Noun Project

- Toilet by Isaac Haq, Noun Project