Author: SCIRE Community Team | Reviewer: Amrit Dhaliwal | Published: 5 July 2019 | Updated: ~

Acupuncture is a common complementary therapy used for various symptoms and conditions. This page outlines what acupuncture and dry needling are and their uses after spinal cord injury (SCI).

Key Points

- Acupuncture is a treatment where small thin needles are inserted into specific points on the body to treat health conditions. Acupuncture is a complementary and alternative medicine treatment based on traditional Chinese medicine.

- Acupuncture has been studied as a treatment for pain, bladder problems, and to aid functional recovery after SCI.

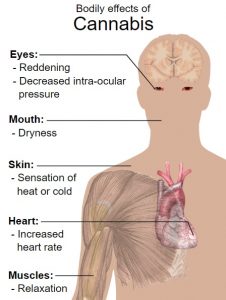

- Scientists are not entirely sure how acupuncture might work. Its effects on pain, bladder function, and functional recovery after SCI are likely related to influences on the nervous system and/or circulation.

- Overall, there is moderate evidence suggesting that acupuncture (including electroacupuncture) may be effective for treating neuropathic pain and bladder problems after SCI; and may aid functional recovery after SCI. The evidence for treating shoulder pain is unclear. Further studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Acupuncture needles are thin needles that are inserted into acupuncture points on the body.1

Acupuncture is a complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) practice that has been used for thousands of years as a component of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). Acupuncture involves the insertion of small thin needles into specific points on the body called acupuncture points or acupoints.

Acupuncture is used to treat many different symptoms and conditions. For people with SCI, acupuncture is used to treat pain, manage bladder problems, and possibly aid functional recovery.

Dry needlingDry needling, also known as intramuscular stimulation (IMS), involves the use of similar thin needles that are inserted into trigger points. Trigger points are tight, irritable bands in the muscles and fascia that are a common cause of musculoskeletal pain. Dry needling typically elicits a small muscle twitch that may help to reduce muscle tension. Acupuncture and dry needling differ in both the theories that underlie their use and in how they are practiced. |

Acupuncture is performed by health providers such as physiotherapists, physicians, chiropractors, and acupuncturists. In many regions, health providers need special training and a license to practice acupuncture.

Before the treatment

If you are considering trying an acupuncture treatment, it is important to discuss with your health providers to make sure that acupuncture is safe for you. Before starting a treatment, your health provider will perform an assessment and provide information about the treatment, its risks, and any other information you need to decide whether to proceed with an acupuncture treatment.

During the treatment

Acupuncture points are located at very specific points on the body.2

Acupuncture needles are thin, single-use, sterile needles that are solid and cannot be used to inject or withdraw fluids from the body. The needles are inserted into the surface of the skin at locations called acupuncture points. Acupuncture points are specific points on the body that are thought to influence the body systems. When the needles are inserted into the skin, they can cause minimal pain and/or bleeding.

Once the acupuncture needles are inserted, they may be left in for a specific amount of time determined by the therapist (usually 20 minutes or longer) before removal. Your response will be monitored during and after the treatment. While the needles are inserted, some practitioners choose to twist or shallowly plunge the needles into the skin or apply other stimulation in the form of heat or electricity to the needles. Acupuncture treatments are usually scheduled anywhere from a few days to a week apart.

Traditional Chinese medicine explanation

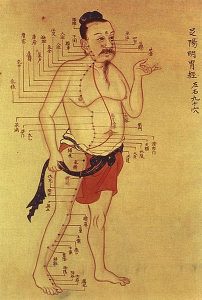

Ancient illustration of the acupuncture meridians based on Traditional Chinese Medicine.3

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is based on the belief that illness happens because of imbalances in energy flow in the body. This energy flow is known as Qi (pronounced ‘chee’) and is thought to flow along lines of energy in the body called meridians. Traditional acupuncture points are located where these lines are believed to pass close to the surface of the skin. Thus, stimulating acupuncture points with needles is thought to promote balance of the body’s energy and treat health conditions.

Modern explanations

Traditional explanations for how acupuncture works do not align well with modern science. Scientists are not entirely sure how acupuncture might work, but its effects are likely related to influences on the nervous system and/or circulation.

Pain

Scientists have proposed several possible explanations for how acupuncture could work to reduce pain:

- By blocking pain from traveling in the nerves

- By causing the body to release substances that prevent pain (such as endorphins)

- By altering blood circulation in important areas of the body

Bladder problems

Acupuncture may affect bladder function by influencing nerve signals or control centers for urination in the brain and spinal cord.

Functional recovery

Acupuncture has been proposed as a treatment to improve recovery of function after SCI. This is not well understood, but some scientists have proposed that it may be related to reducing damage caused by the after-effects of the injury.

There are certain situations in which acupuncture may not be safe to use. This is not a complete list; please consult a health provider for detailed safety information before using this treatment.

Acupuncture should be used with caution in the following situations:

- By certain groups of people, such as children, pregnant women, and people with medical conditions (such as heart conditions, osteoporosis, or weakened immune systems)

- Near major organs (such as certain places on the torso or neck)

- By people who are prone to fainting or have a fear of needles

- By people who are prone to autonomic dysreflexia

- By people who are at risk of bleeding (including people taking anticoagulants)

- By people who are unable to follow instructions or provide accurate feedback

Acupuncture should not be used in the following situations:

- By people with metal allergies

- In areas with open, infected, inflamed skin or recent surgery

- Near tumors

Even for people who are not restricted from using acupuncture (see above), there may be risks and side effects with the use of this treatment. The common side effects of acupuncture are usually mild and serious complications are rare. However, it is important to discuss these possibilities in detail with your health provider before using this treatment.

Common risks and side effects of acupuncture may include:

- Bruising, bleeding, and skin irritation

- Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea

- Headaches

- Sweating

- Dizziness and fainting

- Worsening of symptoms (like increased pain or muscles spasms)

For people with SCI (especially those with injuries above the level of T6), acupuncture needles may be a cause of irritation to the body if they are placed below the level of injury. This could increase the risk of autonomic dysreflexia in some people.

Rare complications of acupuncture may include:

- Puncture of the lung (pneumothorax) or other internal organs

- Nerve injury

- Infection or spread of infectious diseases (such as Hepatitis B)

- Needles breaking after they are inserted and becoming embedded in the skin

- Convulsions

Many of the rare complications of acupuncture can result from improper acupuncture technique. Technique is a very important part of ensuring safety, and there can be major risks if acupuncture is performed incorrectly. For example, improper needle placement and not using properly sterilized needles or sterile technique can put a person at risk of complications. Because of these risks, it is important that acupuncture is only performed by a trained health provider.

Acupuncture for pain after SCI

Research has studied acupuncture for the treatment of several different types of pain after SCI, including neuropathic pain and shoulder pain.

Shoulder pain

The evidence is unclear about whether acupuncture helps to reduce shoulder pain after SCI. Two studies have compared acupuncture to other treatments, including a sham treatment and a movement therapy called Trager therapy. Although both of these studies found that acupuncture helped with shoulder pain after SCI, it was not more effective than the comparison treatments. Further research is needed to determine effectiveness.

Neuropathic pain

Moderate evidence from three studies suggests that acupuncture may reduce neuropathic pain after SCI. However, two of these studies were low quality so further research is needed to confirm this.

Acupuncture for bladder problems after SCI

Three studies have studied acupuncture as a treatment for bladder problems after SCI. These studies provide moderate evidence that electroacupuncture used together with conventional therapies may help people with SCI to develop effective bladder management earlier after injury.

Another small study provides weak evidence that regular needle acupuncture may help with bladder incontinence caused by hyperreflexic bladder.

Acupuncture for improving functional recovery after SCI

One study has investigated acupuncture for improving functional recovery after SCI. It provides moderate evidence that acupuncture helps to improve functional recovery early after SCI. However, other researchers have debated the quality of the study and whether its conclusions were accurate. More studies are needed to confirm whether acupuncture has any effects on the recovery of function after SCI.

Overall, there is moderate evidence suggesting that acupuncture (including electroacupuncture) may be effective for treating neuropathic pain, bladder problems, and possibly for improving functional recovery after SCI. The evidence for shoulder pain is unclear. Further studies are needed to confirm these findings.

There have not been any studies on whether dry needling is effective for treating people with SCI.

Acupuncture needs to be used with caution in certain situations, but overall is a safe treatment when performed by a trained practitioner. Until more research is done, it is best to discuss this treatment with your health provider to find out more about if it is a suitable treatment option for you.

For a review of how we assess evidence at SCIRE Community and advice on making decisions, please see SCIRE Community Evidence.

Mehta S, Teasell RW, Loh E, Short C, Wolfe DL, Hsieh JTC (2014). Pain Following Spinal Cord Injury. In Eng JJ, Teasell RW, Miller WC, Wolfe DL, Townson AF, Hsieh JTC, Connolly SJ, Noonan VK, Loh E, McIntyre A, editors. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence. Version 5.0: p 1-79.

Available from: https://scireproject.com/evidence/rehabilitation-evidence/pain-management/

Hsieh J, McIntyre A, Iruthayarajah J, Loh E, Ethans K, Mehta S, Wolfe D, Teasell R. (2014). Bladder Management Following Spinal Cord Injury. In Eng JJ, Teasell RW, Miller WC, Wolfe DL, Townson AF, Hsieh JTC, Connolly SJ, Noonan VK, Loh E, McIntyre A, editors. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence. Version 5.0: p 1-196.

Available from: https://scireproject.com/evidence/rehabilitation-evidence/bladder-management/

Connolly SJ, McIntyre A, Mehta, S, Foulon BL, Teasell RW. (2014). Upper Limb Rehabilitation Following Spinal Cord Injury. In Eng JJ, Teasell RW, Miller WC, Wolfe DL, Townson AF, Hsieh JTC, Connolly SJ, Noonan VK, Loh E, McIntyre A, editors. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence. Version 5.0: p 1-77.

Available from: https://scireproject.com/evidence/rehabilitation-evidence/upper-limb/

Evidence for “Acupuncture for pain after SCI” is based on:

Shoulder pain

[1] Dyson-Hudson TA, Shiflett SC, Kirshblum SC, Bowen JE, Druin EL. Acupuncture and trager psychophysical integration in the treatment of wheelchair user’s shoulder pain in individuals with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehab 2001;82:1038-46.

[2] Dyson-Hudson TA, Kadar P, LaFountaine M, Emmons R, Kirshblum SC, Tulsky D et al. Acupuncture for chronic shoulder pain in persons with spinal cord injury: a small-scale clinical trial. Arch Phys Med Rehab 2007;88:1276-83.

Neuropathic pain

[1] Norrbrink C, Lundeberg T. Acupuncture and massage therapy for neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury: An exploratory study. Acupunc Med 2011;29:108-15.

[2] Rapson LM, Wells N, Pepper J, Majid N, Boon H. Acupuncture as a promising treatment for below-level central neuropathic pain: A retrospective study. J Spinal Cord Med 2003;26:21-6.

[3] Nayak S, Shiflett SC, Schoenberger NE, Agostinelli S, Kirshblum S, Averill A et al. Is acupuncture effective in treating chronic pain after spinal cord injury? Arch Phys Med Rehab 2001;82:1578-86.

References for Acupuncture for bladder problems after SCI:

[1] Cheng P-T, Wong M-K, Chang P-L. A therapeutic trial of acupuncture in neurogenic bladder of spinal cord injured patients-A preliminary report. Spinal Cord 1998;36(7):476-480.

[2] Honjo H, Naya Y, Ukimura O, Kojima M, Miki T. Acupuncture on clinical symptoms and urodynamic measurements in spinal-cord-injured patients with detrusor hyperreflexia. Urol Int. 2000;65(4):190-5.

[3] Liu Z, Wang W, Wu J, Zhou K, Liu B. Electroacupuncture improves bladder and bowel function in patients with traumatic spinal cord injury: results from a prospective observational study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:543174

[4] Gu XD, Wang J, Yu P, Li JH, Yao YH, Fu JM, Wang ZL, Zeng M, Li L, Shi M, Pan WP. Effects of electroacupuncture combined with clean intermittent catheterization on urinary retention after spinal cord injury: a single blind randomized controlled clinical trial. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015 Oct 15;8(10):19757-63.

References for Acupuncture for functional recovery after SCI:

[1] Wong AM, Leong CP, Su TY, Yu SW, Tsai WC, Chen CP. Clinical trial of acupuncture for patients with spinal cord injuries. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2003 Jan;82(1):21-7.

Other references:

Ma R, Liu X, Clark J, Williams GM, Doi SA. The Impact of Acupuncture on Neurological Recovery in Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Neurotrauma. 2015 Dec 15;32(24):1943-57.

Dorsher PT, McIntosh PM. Acupuncture’s Effects in Treating the Sequelae of Acute and Chronic Spinal Cord Injuries: A Review of Allopathic and Traditional Chinese Medicine Literature. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:428108.

Wang J, Zhai Y, Wu J, Zhao S, Zhou J, Liu Z. Acupuncture for Chronic Urinary Retention due to Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:9245186.

Shin BC, Lee MS, Kong JC, Jang I, Park JJ. Acupuncture for spinal cord injury survivors in Chinese literature: a systematic review. Complement Ther Med. 2009 Oct-Dec;17(5-6):316-27.

NIH consensus conference. Acupunc JAMA 1998;280:1518-24.

Pomeran ZB. Scientific basis of acupuncture. In: Stux G, Pomeran (Eds.). Basis of acupuncture (pp. 6-72). 4 Rev Ed. Springh-Verlag. 1998.

Wong JY, Rapson LM. Acupuncture in the management of pain of musculoskeletal and neurologic origin. Phys Med Rehab Clin North Am 1999;10:531-45.

Zhang T, Liu H, Liu Z, Wang L. Acupuncture for neurogenic bladder due to spinal cord injury: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. 2014 Sep 10;4(9):e006249.

Lee MHM, Liao SJ. Acupuncture in physiatry, in Kottke FJ, Lehmann JF (eds). Krusens Handbook of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, ed. 4. Philadelphia: Saunders 1990:402-32.

Chung A, Bui L, Mills, E. Adverse effects of acupuncture. Which are clinically significant? Canadian Family Physician. 2003;49:985–989.

White A. A cumulative review of the range and incidence of significant adverse events associated with acupuncture. Acupunct Med. 2004 Sep;22(3):122-33.

Ansari NN, Naghdi S, Fakhari Z, Radinmehr H, Hasson S. Dry needling for the treatment of poststroke muscle spasticity: a prospective case report. NeuroRehabilitation. 2015;36(1):61-5.

Salom-Moreno J, Sánchez-Mila Z, Ortega-Santiago R, Palacios-Ceña M, Truyol-Domínguez S, Fernández-de-las-Peñas C. Changes in spasticity, widespread pressure pain sensitivity, and baropodometry after the application of dry needling in patients who have had a stroke: a randomized controlled trial. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2014 Oct;37(8):569-79.

Dunning J, Butts R, Mourad F, Young I, Flannagan S, Perreault T. Dry needling: a literature review with implications for clinical practice guidelines. Phys Ther Rev. 2014 Aug;19(4):252-265.

Averill A, Cotter AC, Nayak S, Matheis RJ, Shiflett SC. Blood pressure response to acupuncture in a population at risk for autonomic dysreflexia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000 Nov;81(11):1494-7.

Gattie E, Cleland JA, Snodgrass S. The Effectiveness of Trigger Point Dry Needling for Musculoskeletal Conditions by Physical Therapists: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017 Mar;47(3):133-149.

Image credits:

- ‘Acupuncture’, ©Magali M , CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

- By thepismire, ‘her handiwork’, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

- Acupuncture meridian illustration: This image is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries, and is identified as being free of known restrictions under copyright law, including all related and neighboring rights.

- Acupuncture on an arm: Released into the public domain (by the author). There is no copyright associated with this file, and the website has released all ownership to the public domain.

- Stock image of back pain, ©3dman_eu, CC0.