Author: Kelsey Zhao | Reviewer: James Milligan | Published: 19 March 2025 | Updated: ~

SCIRE would like to acknowledge the staff at Spinal Cord Injury BC who contributed invaluable knowledge and experience to the development of this article.

Key Points

- Primary care providers (PCPs) help manage your health over a lifetime. They can diagnose and treat common health concerns and coordinate specialist health care.

- See your PCP whenever you have a concern about your health and discuss the possibility of annual check-ups.

- In this article, we provide a thorough guide to preparing for an appointment with a PCP after spinal cord injury.

- Health checklists can help you and your PCP make sure routine tests and screenings are done.

- There are many online resources and local organizations your PCP can consult to learn more about providing care to people with spinal cord injury.

Primary care providers (PCPs) take care of the day-to-day health of people at all stages of life. They are often the first contact when someone has a non-emergency health concern. This person is often a family doctor, but the role can also be filled by a nurse practitioner, physician assistant. They play a central role in the care team for people with spinal cord injury (SCI) and you will maintain a relationship with your PCP for many years. The responsibilities of a PCP include:

Primary care providers (PCPs) take care of the day-to-day health of people at all stages of life. They are often the first contact when someone has a non-emergency health concern. This person is often a family doctor, but the role can also be filled by a nurse practitioner, physician assistant. They play a central role in the care team for people with spinal cord injury (SCI) and you will maintain a relationship with your PCP for many years. The responsibilities of a PCP include:

- Diagnose and treat common health conditions.

- Encourage and provide advice for a healthy lifestyle.

- Conduct preventative screenings, tests, and checks.

- Refer more complex or specific problems to specialists or programs.

- Coordinate the care you receive from specialists, programs, etc.

People with SCI should see a PCP whenever there is a health concern that needs to be addressed. Due to complex health issues, people with SCI should discuss with their PCP whether an annual physical check-up would be suitable.

If you have a health concern and do not have or cannot reach a PCP, consider virtual health services, telehealth services, and walk-in clinics. If you need immediate care, please visit an urgent care/treatment centre. If your condition is severe or life-threatening, go to your nearest Emergency Room or call your regional emergency phone number.

If you do not have a PCP, find out if there is a community or government registry that will put you on a waitlist to find one.

Go to an urgent care/urgent treatment centre if…

- You need immediate care, and you cannot get an appointment with your PCP soon enough (for example, an infection or pressure injury that will get worse with time).

Go to the emergency room or call your regional emergency number if…

Go to the emergency room or call your regional emergency number if…

- Your condition is getting worse very quickly.

- You condition is life-threatening.

- You have autonomic dysreflexia that is not responding well to treatment.

- The problem is time-sensitive, and you cannot get an appointment with your PCP soon enough and there is no urgent care centre nearby.

Appointments with PCPs are often short in time. This guide offers recommendations to help make the most of your appointment. Most PCPs do not have many patients with SCI and are not familiar with SCI-related health care needs. Although people with SCI should not be responsible for educating others on SCI, being on top of your own needs is important. Becoming an expert in your own health can help you work with your PCP as a team and keep you healthy.

Write down what you want to address in the appointment

- Current health concerns. Gather information to try and understand the problem, what may be causing it, and possible solutions

- Questions you have about your health or potential treatments/therapies

- Prescriptions that need to be refilled

- Forms and referrals that need to be filled out and signed. For referrals to programs, check that you meet the eligibility requirements. If a referral letter is required, it may speed things along to present an initial draft of the letter to your PCP.

It is possible that all you concerns cannot be addressed in a single appointment. Set priorities by keeping in mind which concerns you want addressed as soon as possible and which ones can wait for another appointment.

Bring up to date medical and health information

Make sure your PCP is up to date on your medical history. For your own records, it can be helpful to keep a folder for your personal medical and health information. This could be a physical folder or a digital one. These records may include:

- A health journal: Keep a journal of ongoing health concerns, the symptoms you are experiencing, and your day-to-day activities. This gives your doctor more information to better understand and address the issue (for example, if you are experiencing persistent urinary tract infections, a bladder journal might help you find the root cause). The SCI Health Toolkit App is a free, easy-to-use tool designed to help you track and monitor health changes, and walk you through health checks.

- Medications: Note the name of the medication, the dose and when a refill is needed. Free apps like the Medisafe App can help you keep track of your medications.

- Other treatments or supplements: Include any over-the-counter medication, vitamins, and natural remedies that you are taking. Note any alternative medicine treatments you are using.

- Tests screenings: Keep track of routine tests/screening and when the next one should be scheduled. Keep a record of test results and imaging results if available.

Accessibility

If this is your first appointment with your PCP since your injury, you may need to phone or visit their office to ask about accessibility.

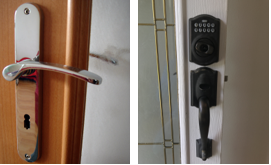

Building accessibility

- Accessible parking

- Accessible routes into and throughout the building

- Automatic power doorways

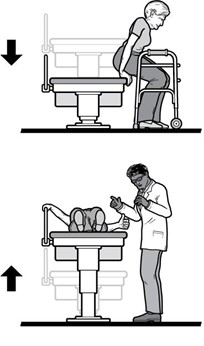

Medical equipment accessibility

- Adjustable height accessible exam table

- Transfer and lift equipment

- Wheelchair accessible scales

Scheduling flexibility

- Appointments later in the day

- Appointments scheduled around other health-related commitments like physiotherapy or a bowel routine.

- Longer appointments to accommodate complex health issues, transfers, skin inspections etc.

- Virtual or telephone appointments for certain concerns.

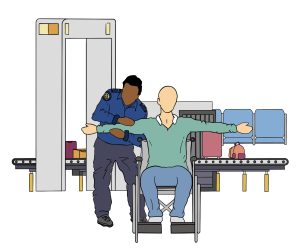

Physical Exams

There are many screenings, tests, and checks that require an in-person procedure where your body is examined by looking, feeling, using medical tools, or taking a sample of cells. You may also be required to transfer for the procedure. Being prepared and informed for these procedures can make your experience safer and more comfortable. Some tips to keep in mind:

Equipment for exams

- If accessible equipment like an adjustable exam table is not available, bring a caregiver, friend, or family who can help you transfer safely and stay at the side of the table to prevent falls.

- If accessible equipment is required for the procedure, you or your PCP may need to reach out to get the procedure done at another clinic or hospital that has the equipment.

Health complications during exams

- Before starting, have a conversation with your PCP about issues that might come up during the procedure and how to address them.

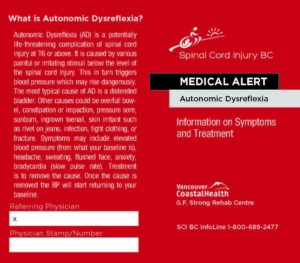

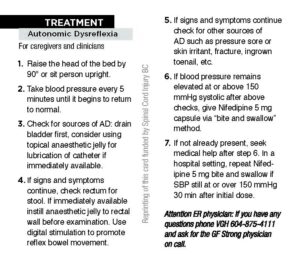

- For people with an injury above T6, a procedure below the injury can trigger autonomic dysreflexia (AD). Inform your PCP about the triggers, symptoms and how to manage your AD. Consider measuring blood pressure before and after the procedure to monitor for AD.

- Depending on your bowel and bladder dysfunction, accidents may happen during procedures. Empty the bowel bladder before an exam of the pelvic region and let your PCP know if you may have an accident during the procedure.

- If you experience muscle spasms that could affect the procedure, discuss triggers and how to manage spasticity with your PCP.

If a physical exam is not necessary, virtual appointments and phone appointments with your PCP may be a suitable option.

Refer to our articles on Autonomic Dysreflexia, Urinary Tract Infections, and Spasticity for more information!

Practical Tips

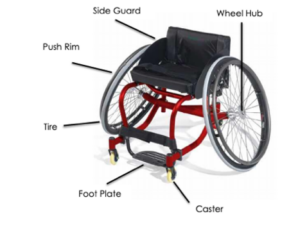

- Ask if a note can be added to your profile about physical disability and use of mobility aid(s) so that staff knows to book you in an accessible exam room.

- Make sure everyone who provides health care to you sends notes, images, and results to your PCP, who is responsible for coordinating your care.

- Be aware of other services in the community (such as labs, imaging centres, and specialist offices) that have accessible equipment.

- Wallet cards are small cards available for free that provide basic information on common SCI complications: autonomic dysreflexia, urinary tract infections, and pressure injuries. Keep them on you to give to your PCP at an appointment or to first responders and paramedics in an emergency. Wallet cards can be printed at home or mailed from livingwithsci.ca/wallet-information-cards.

- Request a “standing order” for laboratory tests done often like bloodwork and urine tests so that you don’t need to make an appointment every time.

- Request clean empty urine containers for when you need to test for urinary tract infection. You may need to explain to your PCP that urinary tract infections are common for people with SCI.

| People with SCI have a higher risk for antibiotic resistance. Avoid using antibiotics to prevent UTI or to treat unspecific symptoms that could be caused by something else. Inappropriate use of antibiotics can lead to infections with antibiotic resistant bacteria, that cannot be treated with common medications. |

During the appointment

- Take notes or ask if you can record the appointment so you do not have to worry about remembering everything your PCP says and follow up with tasks as needed.

- Ask questions or ask for more information if you are unsure or don’t understand something.

- If you are nervous, bring a caregiver/friend/family member who can help take notes and help advocate for your needs.

Reach out to other people with SCI/peer support programs

Attending peer programs or calling a help line run by SCI organizations can connect you with someone who can help you prepare for the appointment. Often, another person with SCI will have had similar health issues and can provide advice on how to address it with your PCP. There may also be people or programs that can help you prepare documents or do research.

SCI-specific health checks

Checklists made for people with SCI can help keep you and your PCP on top of routine exams and tests. They can also help you find the language to ask and talk about health issues.

The American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) has checklists for people with SCI.

- Annual Health Maintenance Checklist for SCI-specific health checks that should be done on a regular basis.

- Episodic Care Tips Checklist for addressing specific SCI-related complications.

If your PCP is interested in more in-depth information, case studies, advice, and guidelines for these checklists and SCI-specific care, they can check out the Primary Care Article series from ASIA’s peer-reviewed journal. For brief overviews on managing common SCI complications in primary care, they can visit the Primary Care section on the SCIRE Professional website.

If your PCP is interested in more in-depth information, case studies, advice, and guidelines for these checklists and SCI-specific care, they can check out the Primary Care Article series from ASIA’s peer-reviewed journal. For brief overviews on managing common SCI complications in primary care, they can visit the Primary Care section on the SCIRE Professional website.

Visit SCIRE Professional for more information on Primary Care for SCI

Standard health checks

PCPs should also do the same general health checks and routine screenings that they would for any other patient. The College of Family Physicians of Canada provides Preventative Care Checklists.

Sexual and reproductive health care

Both the public and some health professionals can have the misconception that people with physical disabilities are not sexually active, at risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), interested in sexual activity, or interested in having kids. Initiate a conversation with your PCP if you have questions or concerns about sexual health (challenges with sexual activity, contraception, sexually transmitted diseases), reproductive health (fertility, pregnancy, family planning), or menstruation/menopause.

If your PCP is interested in learning more to better care for people with SCI and people with disabilities, there are many resources they can consult. See a selection of free resources below:

Online resources

American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) – SCI Healthcare Resources for Primary Care Providers

asia-spinalinjury.org/primary-care

Online hub providing a variety of resources for family physicians caring for patients with spinal cord injury from guides to make a health facility accessible, to SCI care information, to patient education materials.

Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) – Access to Medical Care for Individuals With Mobility Disabilities

ada.gov/resources/medical-care-mobility

Online guide to making a health care facility accessible to people with mobility disabilities. Includes answers to commonly asked questions.

Spinal Cord Injury Research Evidence (SCIRE) Professional – Primary Care

SCIRE Professional provides systematic reviews of spinal cord injury (SCI) research, to allow researchers and health professionals to guide their practice based on current best evidence. This includes a section specifically for primary care providers.

Spinal Cord Injury Research Evidence (SCIRE) Community

SCIRE Community provides free information about spinal cord injury research that is written in everyday language.

Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center (MSKTC) – Spinal Cord Injury Factsheets

Online factsheets providing information on the changes that come with living with spinal cord injury.

International Spinal Cord Society (ISCoS) – Global Education Initiative

Online learning module for health care providers on rehabilitation and management for SCI.

Connect with SCI organizations and specialists

Local non-profit SCI organizations, rehabilitation centres, and SCI centres can be excellent resources for region-specific information and advice. Regular communication with SCI-related specialists can also be helpful for both coordinating care and sharing knowledge.

Primary care providers have an invaluable role in the care team for people with SCI. They provide diagnoses, treatments, advice, referrals to specialist services, and conduct preventative screenings and tests.

Being prepared for your appointment and staying on top of your health concerns can go a long way in helping your PCP address your concerns. Work together with your PCP to figure out the best way to coordinate your appointments, find solutions for accessibility, and address your health concerns.

There are many free resources available to help people with SCI stay on top of their health and help PCPs provide care to their patients with SCI.

For a review of how we assess evidence at SCIRE Community and advice on making decisions, please see SCIRE Community Evidence.

SCIRE Community. “Autonomic Dysreflexia”

SCIRE Community. “Urinary Tract Infections”

SCIRE Community. “Spasticity”

SCI-BC Wallet Cards

Health Tracking Mobile Apps:

Health Checklists:

- American Spinal Injury Association Annual Health Maintenance Checklist

- American Spinal Injury Association Episodic Care Tips Checklist

- College of Family Physicians of Canada Preventative Care Checklists

Resources for Primary Care Providers:

- American Spinal Injury Association Primary Care Article series

- American Spinal Injury Association SCI Healthcare Resources for Primary Care Providers

- Americans with Disabilities Act Access to Medical Care for Individuals with Mobility Disabilities

- SCIRE Professional Primary Care

- Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center Spinal Cord Injury Factsheets

- International Spinal Cord Society Global Education Initiative

Evidence for “What is a primary care provider?” is based on:

Holland, K. (2023, June 29). Types of Doctors: PCP vs. Family Doctor vs. Internist. https://www.healthline.com/find-care/articles/primary-care-doctors/types-of-doctors#internist

McColl, M. A., Aiken, A., McColl, A., Sakakibara, B., & Smith, K. (2012). Primary care of people with spinal cord injury: scoping review. Canadian Family Physician Medecin de Famille Canadien, 58(11), 1207–1216, e626-35.

Evidence for “When should I see my primary care provider?” is based on:

McColl, M. A., Aiken, A., McColl, A., Sakakibara, B., & Smith, K. (2012). Primary care of people with spinal cord injury: scoping review. Canadian Family Physician Medecin de Famille Canadien, 58(11), 1207–1216, e626-35.

Evidence for “How do I prepare for an appointment?” is based on:

How to Prepare for a Doctor’s Appointment | National Institute on Aging. (2020, February 3). NIH National Institue on Aging. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/medical-care-and-appointments/how-prepare-doctors-appointment

Making the Most of Your Appointment | HealthLink BC. (2022, November 14). Healthlink BC. https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/health-topics/making-most-your-appointment

Access to Medical Care for Individuals with Mobility Disabilities | ADA.gov. (2020, June 26). https://www.ada.gov/resources/medical-care-mobility/

Phelan, S. T., & Unser, C. (2020, March 13). Eight tips to improve outpatient visits for spinal cord injury patients. https://www.contemporaryobgyn.net/view/eight-tips-improve-outpatient-visits-spinal-cord-injury-patients

Evidence for “What should I ask my primary care provider to check?” is based on:

Hough, S., Cordes, C. C., Goetz, L. L., Kuemmel, A., Lieberman, J. A., Mona, L. R., Tepper, M. S., & Varghese, J. G. (2020). A Primary Care Provider’s Guide to Sexual Health for Individuals With Spinal Cord Injury. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation, 26(3), 144–151. https://doi.org/10.46292/sci2603-144

Image credits

- Doctor smiling ©SCIRE, CC BY-NC 4.0

- Ambulance by Dahlia nur aini, the Noun Project

- Question by Yunita Bela, the Noun Project

- Automatic doorway ©SCIRE, CC BY-NC 4.0

- Accessible parking ©SCIRE, CC BY-NC 4.0

- Adjustable-height exam table by S. Department of Justice (Disability Rights Section)

- Autonomic Dysreflexia Wallet Card by Spinal Cord Injury BC

- Notes by Qadeer Hussain, the Noun Project

- Checklist by Anggara Putra, the Noun Project

Employment

Employment Social support refers to one’s relationships with other people, and the interactions, support, and care provided by this network of people, including family members, friends, and peer community. There is consistent evidence that more social support is linked to higher QoL in people with SCI.

Social support refers to one’s relationships with other people, and the interactions, support, and care provided by this network of people, including family members, friends, and peer community. There is consistent evidence that more social support is linked to higher QoL in people with SCI.

I was skiing when I broke my neck. I had just turned 19, living in Vancouver. I went on a run that was steep and ended up going quite fast and then crashing. Somewhere in the whole thing I felt my neck break. I experienced it as feeling my body was expanding, the size of the universe. I experienced it as a sound like multiple sirens going off, very loud noises going very broadly. Then, I experienced my body going into a fetal position but when I opened my eyes my arms were up here. I said to myself, “You broke your neck – don’t move.” Eventually, people went down and got a piece of plywood to carry me off the mountain. They took me down, sort of bouncing, which is probably where more damage came.

I was skiing when I broke my neck. I had just turned 19, living in Vancouver. I went on a run that was steep and ended up going quite fast and then crashing. Somewhere in the whole thing I felt my neck break. I experienced it as feeling my body was expanding, the size of the universe. I experienced it as a sound like multiple sirens going off, very loud noises going very broadly. Then, I experienced my body going into a fetal position but when I opened my eyes my arms were up here. I said to myself, “You broke your neck – don’t move.” Eventually, people went down and got a piece of plywood to carry me off the mountain. They took me down, sort of bouncing, which is probably where more damage came.

So then, we went into sailing through

So then, we went into sailing through

We were able to put on the Public Salons for about four or five years, having received a million dollars from a foundation in California. We tried to raise additional money to bolster that, but eventually we ran out. We had to try to make it profitable on its own, but it wasn’t designed for fundraising, it was designed for giving me pleasure. Fundraising would be a real challenge. So, we had to totally revolutionize it a couple years ago. What I do now is bring in an international speaker, that’s the star, and then have local responders who give them questions, comments, critiques, etc. So that’s the new model and it seems to be working. I brought in a former chief planner of the World Bank, Alain Bertaud, and a recent Think-Tank Salon included experts on addiction and mental health. In a way, I’m still on those two issues of prices and addiction, now attacking them from outside, not from the inside as mayor.

We were able to put on the Public Salons for about four or five years, having received a million dollars from a foundation in California. We tried to raise additional money to bolster that, but eventually we ran out. We had to try to make it profitable on its own, but it wasn’t designed for fundraising, it was designed for giving me pleasure. Fundraising would be a real challenge. So, we had to totally revolutionize it a couple years ago. What I do now is bring in an international speaker, that’s the star, and then have local responders who give them questions, comments, critiques, etc. So that’s the new model and it seems to be working. I brought in a former chief planner of the World Bank, Alain Bertaud, and a recent Think-Tank Salon included experts on addiction and mental health. In a way, I’m still on those two issues of prices and addiction, now attacking them from outside, not from the inside as mayor.

Ainsley is 17 and plans on doing a Bachelor of Arts at the University of British Columbia after graduating high school this year!

Ainsley is 17 and plans on doing a Bachelor of Arts at the University of British Columbia after graduating high school this year! Dan is 37 and a full-time student at Douglas College in Recreation Therapy! He enjoys cooking and has a dog.

Dan is 37 and a full-time student at Douglas College in Recreation Therapy! He enjoys cooking and has a dog. Caleb is 35 and likes to spend his time outdoors and doing sports like scuba diving, whitewater kayaking and sitskiing!

Caleb is 35 and likes to spend his time outdoors and doing sports like scuba diving, whitewater kayaking and sitskiing!

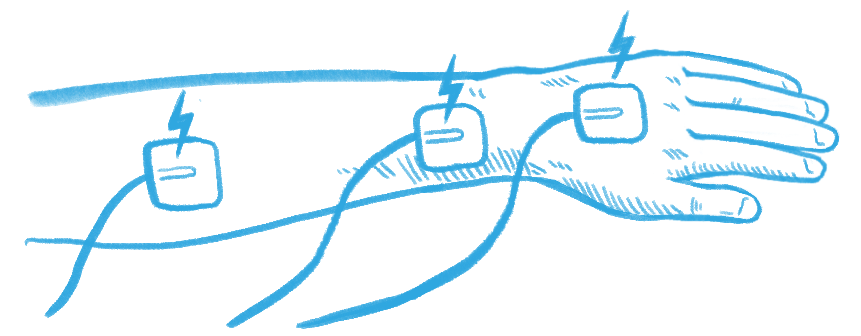

This was very true for Dan. After his nerve transfer surgery, he lost some muscle strength in his left hand and arm. He was still strong enough to push his chair but not to stop. As a result, he went from strictly using a manual chair to using a power wheelchair for about 10 months. The rest of Dan’s recovery did not go so smoothly either. He explains, “in my left arm, when I moved my arm in a certain way, I would get a twang. It felt like I hit my funny bone but times 100. It was really bad and that lasted about two weeks. I also had some numbness in my left thumb all the way down to my palm. I still have numbness but it’s mostly the tip of my thumb so it’s better.” On top of everything, Dan was living at home and not at a rehabilitation centre when he had his surgeries. He came to realize post-surgery that he did not have all the necessary supports in place to accommodate the temporary losses in function. Reflecting on these struggles, he suspects that since people with

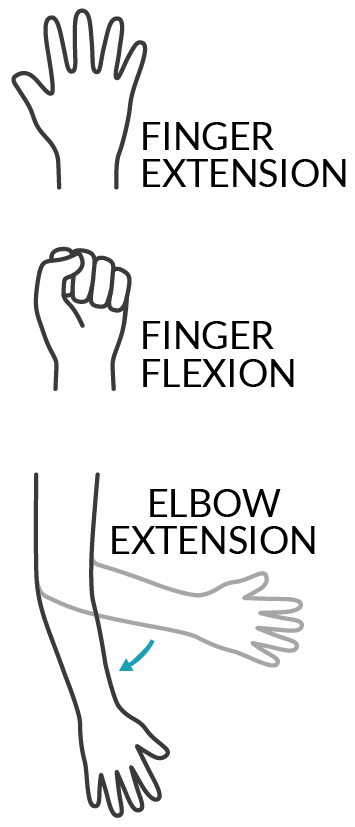

This was very true for Dan. After his nerve transfer surgery, he lost some muscle strength in his left hand and arm. He was still strong enough to push his chair but not to stop. As a result, he went from strictly using a manual chair to using a power wheelchair for about 10 months. The rest of Dan’s recovery did not go so smoothly either. He explains, “in my left arm, when I moved my arm in a certain way, I would get a twang. It felt like I hit my funny bone but times 100. It was really bad and that lasted about two weeks. I also had some numbness in my left thumb all the way down to my palm. I still have numbness but it’s mostly the tip of my thumb so it’s better.” On top of everything, Dan was living at home and not at a rehabilitation centre when he had his surgeries. He came to realize post-surgery that he did not have all the necessary supports in place to accommodate the temporary losses in function. Reflecting on these struggles, he suspects that since people with  Ainsley is now 2 years after the nerve transfers and has gained the ability to fully open both hands. On the left, her restored hand closing from nerve transfer is very strong and she can pick things up. The right-hand pinch gained from the tendon transfer is functional and continues to build strength. All these improvements in her fingers and hands mean that Ainsley can use her cell phone with finger gestures, scratch an itch, adjust her hair, and hold and use things like cutlery, a toothbrush, makeup, and bank cards. The triceps nerve transfer has recovered to the point where she can now extend both arms against gravity. These days, Ainsley is getting ready to hit the road in a custom hand control vehicle, something that would not have been possible if not for the triceps surgeries that improved her strength enough to turn a steering wheel. Hopeful for the future, Ainsley says that she is “still improving everyday”.

Ainsley is now 2 years after the nerve transfers and has gained the ability to fully open both hands. On the left, her restored hand closing from nerve transfer is very strong and she can pick things up. The right-hand pinch gained from the tendon transfer is functional and continues to build strength. All these improvements in her fingers and hands mean that Ainsley can use her cell phone with finger gestures, scratch an itch, adjust her hair, and hold and use things like cutlery, a toothbrush, makeup, and bank cards. The triceps nerve transfer has recovered to the point where she can now extend both arms against gravity. These days, Ainsley is getting ready to hit the road in a custom hand control vehicle, something that would not have been possible if not for the triceps surgeries that improved her strength enough to turn a steering wheel. Hopeful for the future, Ainsley says that she is “still improving everyday”. Dan is coming up on 3 years after the nerve transfers. Although his grip is not strong, it is strong enough that he can use and squeeze the brakes on the new e-bike attachment for his wheelchair, which he would not have been able to do without the nerve transfer. Being able to extend his fingers has made it much easier to open his hand to grasp things and move them around. He has more function in his hands then before, but he still has not recovered some of the strength he lost after the surgeries. Dan described how “Before the surgery I could lift a full backpack of groceries off of the back of my chair now I have difficulty if there’s any weight in my bag.” That said, he is still waiting to see how much he improves, explaining, “…it’s coming, it’s just not there yet. I think they say the plateau is four years for this surgery…”, referencing experts who say that improvements for nerve transfers typically reach their peak at around 4 years.

Dan is coming up on 3 years after the nerve transfers. Although his grip is not strong, it is strong enough that he can use and squeeze the brakes on the new e-bike attachment for his wheelchair, which he would not have been able to do without the nerve transfer. Being able to extend his fingers has made it much easier to open his hand to grasp things and move them around. He has more function in his hands then before, but he still has not recovered some of the strength he lost after the surgeries. Dan described how “Before the surgery I could lift a full backpack of groceries off of the back of my chair now I have difficulty if there’s any weight in my bag.” That said, he is still waiting to see how much he improves, explaining, “…it’s coming, it’s just not there yet. I think they say the plateau is four years for this surgery…”, referencing experts who say that improvements for nerve transfers typically reach their peak at around 4 years. Even though Caleb is only 1 year and 3 months after the nerve transfer and still has a long way to go, he is already happy with the improvements. “Going from zero movement in my fingers to now, it’s kind of huge”. The first big impact the nerve transfers had in Caleb’s day-to-day life was probably around four months in, when he was able to open his hand to grab his toothbrush without any kind of assistance. He can now grab a toothbrush or pop can and hold on to it without a problem. His triceps progress has been harder to pin down. There is some movement in his left arm and a small amount in his right arm but he wonders if that would have come back naturally after SCI regardless of the nerve transfers. Whether or not the improvements came from the nerve transfers or from natural recovery, it has been a big help for Caleb’s mobility and being able to shift and transfer.

Even though Caleb is only 1 year and 3 months after the nerve transfer and still has a long way to go, he is already happy with the improvements. “Going from zero movement in my fingers to now, it’s kind of huge”. The first big impact the nerve transfers had in Caleb’s day-to-day life was probably around four months in, when he was able to open his hand to grab his toothbrush without any kind of assistance. He can now grab a toothbrush or pop can and hold on to it without a problem. His triceps progress has been harder to pin down. There is some movement in his left arm and a small amount in his right arm but he wonders if that would have come back naturally after SCI regardless of the nerve transfers. Whether or not the improvements came from the nerve transfers or from natural recovery, it has been a big help for Caleb’s mobility and being able to shift and transfer.

Staying physically active after SCI is important for your health. There is moderate to

Staying physically active after SCI is important for your health. There is moderate to  Athlete Classification

Athlete Classification

Upright cycles

Upright cycles Tandem bikes

Tandem bikes Arm cycle add-ons

Arm cycle add-ons If you are looking to go on some trails, an off-road wheelchair may appeal to you. These wheelchairs are used for recreational riding, such as going for a hike, or going fishing. Off-road wheelchairs often have larger, knobbier tires that are meant to withstand the trail, roots, and rocks. Like the arm-cycles, off-road wheelchairs come in a variety of set ups. Some setups may look like a typical manual wheelchair, but with larger wheels. There are also ones that are controlled with push-levers (such as the

If you are looking to go on some trails, an off-road wheelchair may appeal to you. These wheelchairs are used for recreational riding, such as going for a hike, or going fishing. Off-road wheelchairs often have larger, knobbier tires that are meant to withstand the trail, roots, and rocks. Like the arm-cycles, off-road wheelchairs come in a variety of set ups. Some setups may look like a typical manual wheelchair, but with larger wheels. There are also ones that are controlled with push-levers (such as the

For those who are interested in competition, wheelchair racing may be an option. Wheelchair race events range from the 100m, 200m, 400m, 800m, 1500m, and 5k distance races in track and field, to marathons. Racing wheelchairs differ from the wheelchairs and cycles listed above in that they typically have two wheels with a third one extended out in front. Ideally, race chairs should be light-weight to enhance performance. When seated, the wheelchair should fit “like a glove”, and there should be little movement in the seat. Unlike arm-cycles, the feet are bent down and kept closer to the body. In addition, specialized rubber gloves are worn to push the rims during races.

For those who are interested in competition, wheelchair racing may be an option. Wheelchair race events range from the 100m, 200m, 400m, 800m, 1500m, and 5k distance races in track and field, to marathons. Racing wheelchairs differ from the wheelchairs and cycles listed above in that they typically have two wheels with a third one extended out in front. Ideally, race chairs should be light-weight to enhance performance. When seated, the wheelchair should fit “like a glove”, and there should be little movement in the seat. Unlike arm-cycles, the feet are bent down and kept closer to the body. In addition, specialized rubber gloves are worn to push the rims during races. Wheelchair tennis is played on the same court as able-bodied tennis, and with similar rules. One rule difference is that in wheelchair tennis, players are allowed two bounces instead of one, and the second bounce can be anywhere – even out of bounds. Although one can play wheelchair tennis in their day chair, tennis wheelchairs are often preferred during play. These wheelchairs are faster, lighter, more agile, and more stable. The wheels on the wheelchair are also angled (i.e., there is more camber ) to allow for more swift turning. For those with limited hand function, taping the racquet to your hand is common practice, though it can take some time to find the optimal tension for you. Therefore, people with all levels of ability can play wheelchair tennis.

Wheelchair tennis is played on the same court as able-bodied tennis, and with similar rules. One rule difference is that in wheelchair tennis, players are allowed two bounces instead of one, and the second bounce can be anywhere – even out of bounds. Although one can play wheelchair tennis in their day chair, tennis wheelchairs are often preferred during play. These wheelchairs are faster, lighter, more agile, and more stable. The wheels on the wheelchair are also angled (i.e., there is more camber ) to allow for more swift turning. For those with limited hand function, taping the racquet to your hand is common practice, though it can take some time to find the optimal tension for you. Therefore, people with all levels of ability can play wheelchair tennis. Basketball

Basketball Wheelchair rugby was developed specifically for people with

Wheelchair rugby was developed specifically for people with

Alpine skiing, also known as downhill skiing, is a sport that individuals with

Alpine skiing, also known as downhill skiing, is a sport that individuals with  Cross Country Skiing

Cross Country Skiing Sledge (Ice) Hockey

Sledge (Ice) Hockey Community Voices: Terry

Community Voices: Terry

Kayaks are available for people with all levels of SCI. While individuals with a lower

Kayaks are available for people with all levels of SCI. While individuals with a lower

Duncan’s Experience

Duncan’s Experience

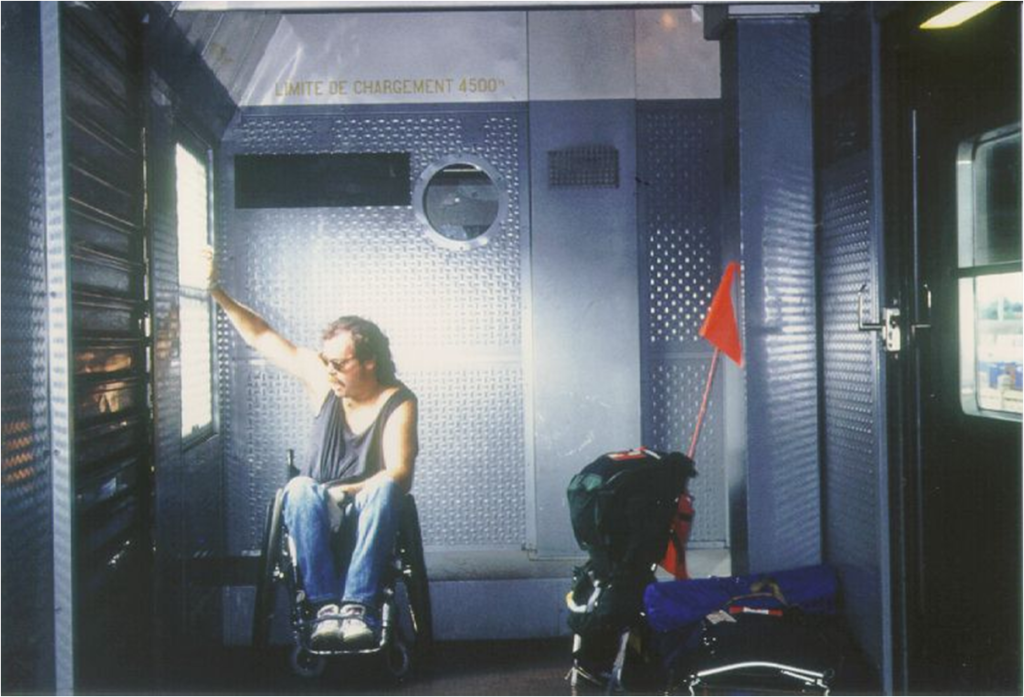

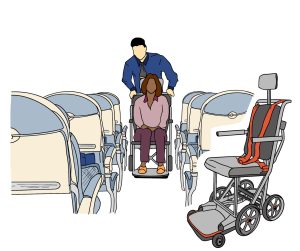

When boarding the plane, you will usually be the first to board. This allows you extra time to transfer to your seat and to get comfortable without the pressure of other passengers waiting in the aisle behind you. Ask the airline about the boarding procedure, as it varies per airline. In general, you will remain in your wheelchair and travel to the door of the plane in it. You will then be transferred into an aisle chair. To facilitate the transfer, ensure you know how to guide the transfer through providing clear, verbal instructions to the airline staff. If you are unable to transfer from an aisle chair into your seat, some airlines have specialized slings that can be used to transfer you into your seat. Similar to the aisle chair, you will need to express your needs and guide your transfer from your wheelchair into the sling.

When boarding the plane, you will usually be the first to board. This allows you extra time to transfer to your seat and to get comfortable without the pressure of other passengers waiting in the aisle behind you. Ask the airline about the boarding procedure, as it varies per airline. In general, you will remain in your wheelchair and travel to the door of the plane in it. You will then be transferred into an aisle chair. To facilitate the transfer, ensure you know how to guide the transfer through providing clear, verbal instructions to the airline staff. If you are unable to transfer from an aisle chair into your seat, some airlines have specialized slings that can be used to transfer you into your seat. Similar to the aisle chair, you will need to express your needs and guide your transfer from your wheelchair into the sling.  The airline staff will then move you to your seat while you are in the sling. Once in your seat, take your wheelchair cushion and any removable parts off your wheelchair, and check that your wheelchair has a gate check tag on it. Make sure that any parts that stick out from your wheelchair are taped to the wheelchair or held in. Also, consider attaching a set of instructions on how to turn on and off a powered wheelchair circuit and how to operate it when the battery is not engaged. Remind the airline staff that your wheelchair will need to go under the plane for the flight. While you are getting settled in your seat, remember to:

The airline staff will then move you to your seat while you are in the sling. Once in your seat, take your wheelchair cushion and any removable parts off your wheelchair, and check that your wheelchair has a gate check tag on it. Make sure that any parts that stick out from your wheelchair are taped to the wheelchair or held in. Also, consider attaching a set of instructions on how to turn on and off a powered wheelchair circuit and how to operate it when the battery is not engaged. Remind the airline staff that your wheelchair will need to go under the plane for the flight. While you are getting settled in your seat, remember to:

As the plane begins to descend, remind the flight attendant that your wheelchair is underneath the plane, and needs to be brought to the door upon landing. During the decent, individuals with limited core function may have some difficulty bracing themselves in the seat. One participant from an interview study explained that it felt like their “body wanted to fling forward”. If you find yourself in this situation, some ways to stabilize yourself in the seat include bracing yourself against the seat in front of you, or hanging onto the arm rests. Some individuals also opt to use a chest strap/abdominal binder to help support their position in the seat during landing.

As the plane begins to descend, remind the flight attendant that your wheelchair is underneath the plane, and needs to be brought to the door upon landing. During the decent, individuals with limited core function may have some difficulty bracing themselves in the seat. One participant from an interview study explained that it felt like their “body wanted to fling forward”. If you find yourself in this situation, some ways to stabilize yourself in the seat include bracing yourself against the seat in front of you, or hanging onto the arm rests. Some individuals also opt to use a chest strap/abdominal binder to help support their position in the seat during landing.

Being able to drive is an important skill that is helpful for day-to-day activities. Research has shown that being able to drive is related to many benefits, such as:

Being able to drive is an important skill that is helpful for day-to-day activities. Research has shown that being able to drive is related to many benefits, such as:

Decide where you will place your wheelchair: in the front passenger seat, or the back seats. Those with weaker shoulder muscles should consider loading their wheelchair into the front seats.

Decide where you will place your wheelchair: in the front passenger seat, or the back seats. Those with weaker shoulder muscles should consider loading their wheelchair into the front seats.

After a spinal cord injury (SCI), there is often an increased need for social support and accessibility in the environment. Due to these factors, careful planning and consideration are required for optimal housing. Housing is an important factor in transitioning back into the community, which is a strong predictor of quality of life. Some (weak) evidence has noted that housing can influence quality of life as it:

After a spinal cord injury (SCI), there is often an increased need for social support and accessibility in the environment. Due to these factors, careful planning and consideration are required for optimal housing. Housing is an important factor in transitioning back into the community, which is a strong predictor of quality of life. Some (weak) evidence has noted that housing can influence quality of life as it:

I work in

I work in

Sherry mused. “As a teenager, when I travelled from my hometown to compete in sports, I had met one or two girls my age with an SCI. As an adult, though, I really didn’t know many girls or women with an SCI. “When I became pregnant with my son, Aidan, I tried to seek out peers that had experienced pregnancy and parenting but with no luck. So, I went through it with a bit of ignorant bliss; with the same angst as any other mom-to-be but not knowing how my body was going to respond as I grew. I soon realized that doing this while living with an SCI … that your disability could be magnified and at times be at the forefront.” When Aidan was born, Sherry and Darryl’s lives changed like any new parents’ lives would. Sherry quickly found ways to adapt to her new life as a mom. Back then it was less about technological help, and more about the mental strength and fortitude to persevere during the ups and downs of raising a child.

Sherry mused. “As a teenager, when I travelled from my hometown to compete in sports, I had met one or two girls my age with an SCI. As an adult, though, I really didn’t know many girls or women with an SCI. “When I became pregnant with my son, Aidan, I tried to seek out peers that had experienced pregnancy and parenting but with no luck. So, I went through it with a bit of ignorant bliss; with the same angst as any other mom-to-be but not knowing how my body was going to respond as I grew. I soon realized that doing this while living with an SCI … that your disability could be magnified and at times be at the forefront.” When Aidan was born, Sherry and Darryl’s lives changed like any new parents’ lives would. Sherry quickly found ways to adapt to her new life as a mom. Back then it was less about technological help, and more about the mental strength and fortitude to persevere during the ups and downs of raising a child.