Authors: Sharon Jang, Dominik Zbogar | Published: 22 February 2022 | Updated: ~

Authors: Sharon Jang, Dominik Zbogar | Published: 22 February 2022 | Updated: ~

Author: Sharon Jang | Reviewers: Phillip Popovich, Katherine Mifflin | Published: 2 September 2020 | Updated: 10 January 2025

The adverse effects of a spinal cord injury (SCI) on the respiratory and immune systems can increase the risk of getting an infectious respiratory condition. This page reviews the relationship between SCI and infectious respiratory conditions.

Key Points

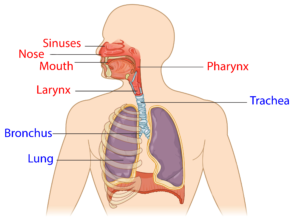

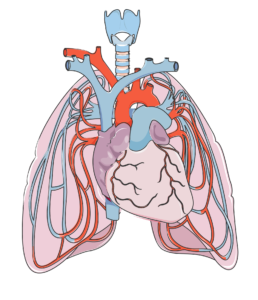

The upper respiratory system (red) and lower respiratory system (blue).1

The respiratory system involves the lungs, and is responsible for breathing, coughing, and speaking. It consists of the upper respiratory tract (nose, mouth, and the throat (pharynx)), and the lower respiratory tract (voice box (larynx), airways (windpipe or trachea), and lungs). Breathing and coughing both depend on various muscles in the chest and neck. Changes to respiratory function after SCI depend on the level of injury and completeness of the injury. After SCI, especially high cervical level injury, some muscles required for breathing may be affected. These include:

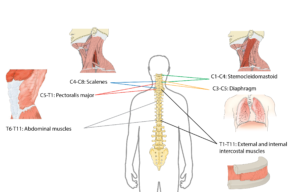

The muscles used to breathe are mostly controlled by the upper parts of the spine.2

As a result, sustaining a higher-level injury may result in impaired respiratory function. Some of these changes include:

Despite these changes, many technologies and techniques are available that can assist with breathing and coughing. Moreover, the greatest amount of air you are able to blow out after taking your biggest breath in increases over time from injury.

For more information, refer to our article on Respiratory Changes After SCI.

The immune system is responsible for fighting infections and preventing illness. To keep our bodies healthy, the immune system does three main things:

The immune system is comprised of two main parts: the innate immune system and the adaptive (or acquired) immune system. The innate immune system refers to a non-specific line of defence (i.e., it acts against all germs in the same manner) that you are born with. It is often the first line of defense, which is made up of parts of your body that prevent germs from entering. This includes:

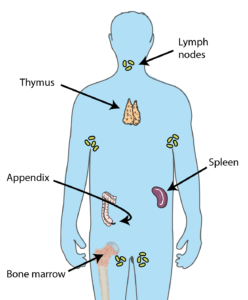

Many organs throughout the body contribute to producing cells required to keep you healthy.3

If germs manage to invade the body, the innate immune system is the first system to recognize them. The innate immune system will then trigger a general attack, such as inflammation and fever. This attack affects the entire body, and does not directly target the germ. Innate immune cells then enlist the help of the adaptive immune system.

The second line of defense involves the adaptive immune system, which initiates specific defences for each germ that enters your body. For example, the body will react differently to a virus that causes influenza versus one that causes measles. The main players in the second line of defense are various types of white blood cells. This includes: natural killer cells, which kill any cell that is not recognized as part of the body, lymphocytes, which help the body remember the invaders for the future and destroy them, and phagocytes, which help “eat” and break up invading organisms.

The cells that contribute to the first and second line of defence are produced in organs all over the body, including the bone marrow, spleen, lymph nodes, adrenal glands, tonsils, and thymus.

Spinal Cord Injury Immune Depression Syndrome (SCI-IDS) is a condition that weakens the immune system after SCI. Weak evidence suggests that SCI-IDS commonly occurs among those with acute SCI. That said, there is also early evidence that SCI-IDS can persist and be present in those with chronic (>1 year) SCI. Although researchers are unsure why the immune system is weakened after SCI, hypotheses have been made:

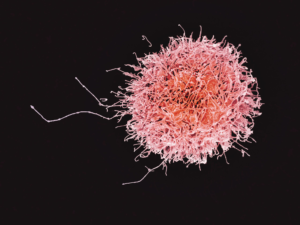

A natural killer cell. The number of these cells is decreased after SCI.4

Weak evidence suggests that immune system changes may occur regardless of level of injury. For example, the amount of natural killer cells are reduced in adults with SCI, regardless of level of injury, in comparison to an able-bodied population. This reduces the body’s ability to fight off germs, which may cause infections, disease, and illnesses. Moreover, early animal research suggests that individuals with SCI may be more susceptible to viruses, such as the flu due to impairments in the body’s immunity. However, it is important to note that these findings have not yet been replicated in humans.

Although the immune system recovers after acute SCI, some (weak) evidence suggests that lowered immunity may extend into the chronic stage of SCI. One study investigated the genes responsible for programming and developing immune cells. The authors found that the genes that normally create natural killer cells are reduced, resulting in lower amounts of these germ-fighting cells throughout the body. A second study supported these findings, as individuals with SCI were found to have lower amounts of natural killer cells in their blood compared to an able-bodied population.

Although the immune system recovers after acute SCI, some (weak) evidence suggests that lowered immunity may extend into the chronic stage of SCI. One study investigated the genes responsible for programming and developing immune cells. The authors found that the genes that normally create natural killer cells are reduced, resulting in lower amounts of these germ-fighting cells throughout the body. A second study supported these findings, as individuals with SCI were found to have lower amounts of natural killer cells in their blood compared to an able-bodied population.

Having an SCI in combination with a weakened immune system has many implications for secondary complications. For example, after SCI many individuals may have difficulties with or be unable to effectively void urine, which encourages the growth of bacteria. This, in combination with a weakened immune system, may explain why urinary tract infections (UTIs) are a common secondary complication of SCI. Although SCI complications and a weakened immune system may contribute to many other secondary complications (e.g., UTI, pressure sores), this article will focus on infectious respiratory conditions that are common with SCI.

For more information, refer to our articles on UTIs and Pressure Injuries!

Respiratory infections can occur in anyone, but people with SCI are at a higher risk for the following reasons:

Reduced/absent respiratory functioning: As people with SCI may have an inability/weakened ability to cough, mucus begins to build up in the airways and the lung. This accumulation of mucus creates a breeding ground for bacteria and viruses.

Reduced/absent respiratory functioning: As people with SCI may have an inability/weakened ability to cough, mucus begins to build up in the airways and the lung. This accumulation of mucus creates a breeding ground for bacteria and viruses.

The heart (in the center) and lungs are complexly interconnected. The lungs help oxygenate the blood, which is pumped by the heart.7

Infectious respiratory diseases can target either the upper respiratory tract (i.e., the nose, mouth, and throat), or the lower respiratory tract (i.e., the voice box, windpipe, airways into the lungs, and the lungs). Oxygen is required for each organ to function properly. When a part of your respiratory system becomes infected, the amount of air you breathe in may be reduced. This reduces the amount of oxygen available for the body, and may quickly affect the function of the brain and other organs. Moreover, these infections can spread all over the body (sepsis). Once it spreads, it becomes more difficult to treat.

As an SCI can negatively affect respiratory and immune function, the rates of respiratory diseases, such as bacterial pneumonia and influenza, among individuals with SCI is high. In fact, respiratory diseases account for just over 80% of all deaths after SCI. In addition, respiratory conditions often present more severely in SCI. This was shown in a (weak evidence) study, where people with SCI who contracted influenza or pneumonia were 37 times more likely to die from the infection compared to an able-bodied population. Two of the most common respiratory infections in people with SCI are pneumonia and the flu. These conditions are particularly infectious, and are caught through tiny droplets of fluid in the air that may be released as a cough or a sneeze. These droplets may fall on surfaces, and can spread if someone touches the surface, then touches their mouth or eyes.

Some (weak evidence) research done to predict who is more likely to experience respiratory illness after SCI indicated that those with a complete injury and those with tetraplegia are at an increased risk of dying from a respiratory related infection. Another study found that during acute care, those with a complete injury were at a greater risk of getting pneumonia. This is related to the lack of/weakened ability to cough and clear mucus from the airways. Secondary complications that may predispose people with SCI to respiratory illnesses include: obesity, heart disease, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic coughing, chronic existence of phlegm, wheezing, and the use of pulmonary medications.

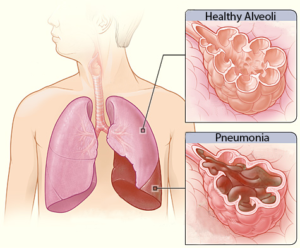

Pneumonia is an infection caused by a bacteria or virus, which leads to an infection of the small air sacs in the lungs. It is one of the most common infections in acute SCI with about 30% of individuals with acute SCI experiencing pneumonia (weak evidence), dropping to about 3.5% in the chronic stages of SCI (i.e., 1-20 years post injury). Although the chance of getting pneumonia decreases after acute SCI, it is important to remember that pneumonia manifests more severely in people with SCI. That is to say, while your chances of getting pneumonia may be reduced at longer times after SCI, if you do get it, it is more severe.

Pneumonia is an infection caused by a bacteria or virus, which leads to an infection of the small air sacs in the lungs. It is one of the most common infections in acute SCI with about 30% of individuals with acute SCI experiencing pneumonia (weak evidence), dropping to about 3.5% in the chronic stages of SCI (i.e., 1-20 years post injury). Although the chance of getting pneumonia decreases after acute SCI, it is important to remember that pneumonia manifests more severely in people with SCI. That is to say, while your chances of getting pneumonia may be reduced at longer times after SCI, if you do get it, it is more severe.

Influenza, or the flu, is a respiratory condition caused by a virus. There are multiple types and sub-types of influenza, although type A and B are the strains that most often cause the flu season. The flu virus affects the nose, throat, and sometimes the lungs, and can lead to secondary conditions such as pneumonia. Flu vaccines are recommended, especially for people with SCI as they are a vulnerable population. There is weak evidence that supports the use of flu vaccines for people with SCI, as their immune system responds similarly to the vaccine compared to able-bodied individuals. That said, those with tetraplegia may have a reduced response to the vaccine. Animal studies suggest that vaccines may be less effective with higher levels of SCI. More research is required to determine the response to influenza vaccines after SCI.

There are many other infectious respiratory conditions that exist, such as the common cold, tuberculosis, and coronaviruses. However, little to no research has been done on the impact of these conditions in the SCI population. Although the available research is limited, it is important to note that individuals with SCI are still at an increased risk of contracting these conditions. The following section describes various respiratory infections in the able-bodied population unless otherwise noted.

Common Cold

The common cold (or simply, the cold) is a general term for a mild upper respiratory tract condition affecting the nose and throat. Common symptoms include stuffy nose, sneezing, sore throat, and cough. Unlike other conditions, there are multiple types of viruses that can cause a cold. Rhinoviruses, coronaviruses, and influenza viruses account for the majority of cases. The cold occurs most frequently in the fall, and decreases upon the arrival of spring. On average, a person will catch the cold once a year, but it is likely that this rate is underestimated.

The common cold (or simply, the cold) is a general term for a mild upper respiratory tract condition affecting the nose and throat. Common symptoms include stuffy nose, sneezing, sore throat, and cough. Unlike other conditions, there are multiple types of viruses that can cause a cold. Rhinoviruses, coronaviruses, and influenza viruses account for the majority of cases. The cold occurs most frequently in the fall, and decreases upon the arrival of spring. On average, a person will catch the cold once a year, but it is likely that this rate is underestimated.

Coronaviruses

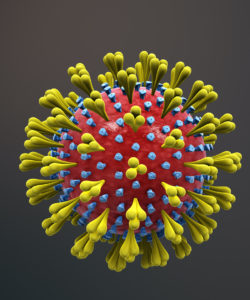

A coronavirus (above), which gets its name from the spikes on the outside that resemble a crown, which is “corona” in Latin.10

Coronaviruses are responsible for many health conditions including the common cold, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), and novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). These are the four strains of coronavirus now known to affect humans, and they are responsible for 10-30% of upper respiratory tract infections. Although these viruses are genetically related, they cause very different conditions. The severity of the conditions they may cause varies from mild (such as the common cold, described above), to severe (such as MERS, SARS, and COVID-19). Though MERS, SARS, and COVID-19 can all lead to pneumonia, each condition affects the body differently: MERS has a greater impact on the digestive system and kidneys, while SARS and COVID-19 most heavily impact the respiratory system, clotting function, and heart activity.

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis is an infection of the lungs that can be caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria. The presence of tuberculosis is higher in developing countries in comparison to developed countries. This is related to factors such as lower rates of vaccination and higher rates of HIV (an immune compromising condition) in developing countries. Treating tuberculosis is particularly difficult, as many strains of the virus/bacteria are resistant to drugs.

Tuberculosis is an infection of the lungs that can be caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria. The presence of tuberculosis is higher in developing countries in comparison to developed countries. This is related to factors such as lower rates of vaccination and higher rates of HIV (an immune compromising condition) in developing countries. Treating tuberculosis is particularly difficult, as many strains of the virus/bacteria are resistant to drugs.

Upper respiratory tract infections

Upper respiratory tract infections are a group of conditions that affect the nose and throat. Some conditions include pharyngitis (sore throat) and laryngitis (inflammation of the voice box; when you lose your voice). These infections are of particular note to those using ventilators, as over 90% of pneumonia and hospitalizations start with an upper respiratory tract infection.

In order to avoid getting infectious respiratory conditions, prevention is key, especially in the community. Here is what you can do to stay healthy:

After an SCI, respiratory functions (i.e., breathing and coughing) and the immune system are compromised. Researchers are still unsure about why the immune system is suppressed. While there is some weak evidence for why the immune system changes after SCI, more clinical trials are required to determine the specific effects of SCI on the immune system.

Given the changes to respiratory and immune functioning after SCI, there is a higher risk of getting an infectious respiratory disease. The best thing to do is to work at prevention, which can be done through a variety of ways such as getting vaccinated and staying hydrated. Discuss all treatment options with your health providers to find out which treatments are suitable for you.

For a review of how we assess evidence at SCIRE Community and advice on making decisions, please see SCIRE Community Evidence.

SCIRE Community. “Respiratory Changes After SCI”. Available from: https://community.scireproject.com/topic/respiratory-changes/

SCIRE Community. “COVID-19 & SCI Infographic”. Available from: https://community.scireproject.com/covid-19/infographics/

Sheel AW, Welch JF, Townson AF (2018). Respiratory Management Following Spinal Cord Injury. In: Eng JJ, Teasell RW, Miller WC, Wolfe DL, Townson AF, Hsieh JTC, Connolly SJ, Noonan VK, Loh E, Sproule S, McIntyre A, Querée M, editors. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence. Version 6.0. Vancouver: p. 1-72.

Available from: https://scireproject.com/evidence/respiratory-management-rehab-phase/

Tortora, G.J., and Derrickson .B.(2013).The Lymphatic System and Immunity. In Roesch, B. (Eds.), Principles of Anatomy and Physiology (pp. 366-447). Biologtical Science Textbooks

Allison, D. J., & Ditor, D. S. (2015). Immune dysfunction and chronic inflammation following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord, 53(1), 14–18. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2014.184

Campagnolo, D. I., Dixon, D., Schwartz, J., Bartlett, J. A., & Keller, S. E. (2008). Altered innate immunity following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord, 46(7), 477–481. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2008.4

Popovich, P., & McTigue, D. (2009). Beware the immune system in spinal cord injury. Nature Medicine, 15(7), 736–737. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm0709-736

Schwab, J. M., Zhang, Y., Kopp, M. A., Brommer, B., & Popovich, P. G. (2014). The paradox of chronic neuroinflammation, systemic immune suppression, autoimmunity after traumatic chronic spinal cord injury. Experimental Neurology, 258, 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.04.023

Riegger, T., Conrad, S., Schluesener, H. J., Kaps, H. P., Badke, A., Baron, C., … Schwab, J. M. (2009). Immune depression syndrome following human spinal cord injury (SCI): A pilot study. Neuroscience, 158(3), 1194–1199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.08.021

Herman, P., Stein, A., Gibbs, K., Korsunsky, I., Gregersen, P., & Bloom, O. (2018). Persons with Chronic Spinal Cord Injury Have Decreased Natural Killer Cell and Increased Toll-Like Receptor/Inflammatory Gene Expression. Journal of Neurotrauma, 35(15), 1819–1829. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2017.5519

Brommer, B., Engel, O., Kopp, M. A., Watzlawick, R., Müller, S., Prüss, H., … Schwab, J. M. (2016). Spinal cord injury-induced immune deficiency syndrome enhances infection susceptibility dependent on lesion level. Brain, 139(3), 692–707. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awv375

Burns, S. P. (2007). Acute Respiratory Infections in Persons with Spinal Cord Injury. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, 18(2), 203–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2007.02.001

Northwest Regional Spinal Cord Injury System. (2004, October 12). Common respiratory problems in SCI – What you need to know. http://sci.washington.edu/info/forums/reports/common_respiratory.asp

DeVivo, M. J., Black, K. J., & Stover, S. L. (1993). Causes of death during the first 12 years after spinal cord injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 74(3), 248–254. https://doi.org/10.5555/uri:pii:000399939390132T

Stolzmann, K. L., Gagnon, D. R., Brown, R., Tun, C. G., & Garshick, E. (2010). Risk factors for chest illness in chronic spinal cord injury: a prospective study. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 89(7), 576–583. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181ddca8e

Berlly, M., & Shem, K. (2007). Respiratory management during the first five days after spinal cord injury. Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine, 30(4), 309–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790268.2007.11753946

McKinley, W. O., Jackson, A. B., Cardenas, D. D., & DeVivo, M. J. (1999). Long-term medical complications after traumatic spinal cord injury: A Regional Model Systems Analysis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 80(11), 1402–1410. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-9993(99)90251-4

Trautner, B. W., Atmar, R. L., Hulstrom, A., & Daroiuche, R. O. (2004). Inactivated Influenza Vaccination for People With Spinal Cord Injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 85(11), 1886–1889. https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2014.371

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020a). Understanding influenza viruses. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/viruses/index.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020b). Prevent seasonal flu. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/index.html

Burns, S. P. (2007). Acute Respiratory Infections in Persons with Spinal Cord Injury. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, 18(2), 203–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2007.02.001

Rao, N. M. (2015). Swine flu the pandemic disease – preventive measures to take. Journal of Medical Science and Technology, 4(1), 1–2.

Heikkinen, T., & Järvinen, A. (2003). The common cold. Lancet, 361(9351), 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12162-9

Paules, Catharine, I., Marston, H. D., & Fauci, A. S. (2020). Coronavirus Infections – More than Just the Common Cold. Journal of the American Medical Association, 323(8), 707–708. https://doi.org/10.1007/82

Stillman, M. D., Capron, M., Alexander, M., Di Giusto, M. L., & Scivoletto, G. (2020). COVID-19 and spinal cord injury and disease: results of an international survey. Spinal Cord Series and Cases, 6(1), 21.

Rodriguez-Cola, M., Jimenez-Velasco, I., Henares-Gutierrez, F., Lopez-Dolado, E., Gambarrutta-Malfatti, C., Vargas-Baquero, E., & Gil-Agudo, A. (2020). Clinical features of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a cohort of patients with disability due to spinal cord injury.

Righi, G., Del, G., & Popolo, G. Del. (2020). COVID-19 tsunami : the first case of a spinal cord injury patient in Italy. Spinal Cord Series and Cases, 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-020-0274-9

Mayo Clinic (2020). Tuberculosis. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/tuberculosis/symptoms-causes/syc-20351250

World Health Organization. (2020). Tuberculosis. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis

LaVela, S. L., Smith, B., & Weaver, F. M. (2007). Perceived Risk for Influenza in Veterans With Spinal Cord Injuries and Disorders. Rehabilitation Psychology, 52(4), 458–462. https://doi.org/10.1037/0090-5550.52.4.458

Ronca, E., Miller, M., Brinkhof, M. W. G., Jordan, X., Léger, B., Baumberger, M., … Fekete, C. (2020). Poor adherence to influenza vaccination guidelines in spinal cord injury: results from a community-based survey in Switzerland. Spinal Cord, 58(1), 18–24. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-019-0333-x

Weaver, F. M., Smith, B., LaVela, S., Wallace, C., Evans, C. T., Hammond, M., & Goldstein, B. (2007). Interventions to increase influenza vaccination rates in veterans with spinal cord injuries and disorders. Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine, 30(1), 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790268.2007.11753908

Author: The SCIRE Professional Team | Reviewers: Cynthia Morin, Andrea Townson | Published: 5 August 2020 | Updated: ~

People living with spinal cord injuries (SCI) have a greater risk of developing more serious symptoms of COVID-19. It is critical for caregivers and attendant services to take the necessary precautions and preventive actions outlined in this document in order to minimize the risk of transmission.

A podcast created by caregivers of BC who share their experiences, “highlighting the joys, trials, and self-discoveries that come along with this rewarding and taxing position”: Caregiving Out Loud Podcast

Advice provided from the Government of Canada for Caregivers in caring for a person with COVID-19 at home

Tip sheet created by the Ontario Caregiver Organization. Provides resources/education on improving caregiver mental health during COVID-19.: Tips for Caregivers Mental Health During COVID-19

The Family Caregivers of BC provide multiple tips and resources for caregivers to practice self-care.: Self-Care Tips During Uncertain Times

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Fact Sheet. (2020, March 4). Retrieved from: (https://shepherd.org/docs/Coronavirus2019_FactSheet_3.4.20.pdf

Public Health Ontario (2020, February 14). Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Self-isolation: Guide for caregivers, household members and close contacts. Retrieved from: https://publichealthontario.ca/-/media/documents/ncov/factsheet-covid-19-guide-isolation-caregivers.pdf?la=en

Public Health Agency of Canada (2020, May 1). How to care for a person with COVID-19 at home: Advice for caregivers. Retrieved from: https://canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/how-to-care-for-person-with-covid-19-at-home-advice-for-caregivers.html

Public Health Ontario (2020, April 10). Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) When and How to Wear a Mask Recommendations for the General Public. Retrieved from: https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/documents/ncov/factsheet/factsheet-covid-19-how-to-wear-mask.pdf?la=en

The Ontario Caregiver Foundation (2020, March 31). COVID-19 – Do you have a plan? Retrieved from: https://ontariocaregiver.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Ontario-Caregiver-Organization-Caregiver-Contingency-Plan.pdf

Family Caregivers of British Columbia (2020, March 11). COVID-19. Retrieved from: https://familycaregiversbc.ca/community-resources/covid-19-virus/

Author: SCIRE Professional Team | Reviewer: Rachael Neal | Published: 5 August 2020 | Updated: ~

Living during the COVID-19 pandemic can be stressful, and it is common to feel worried, sad, or anxious from time to time. This sheet contains information about some resources, techniques, and tips to help support your mental health in the time of COVID-19.

Key Points

Our normal daily routines and activities are changing with the current pandemic situation, which can feel unsettling. You may find that some things you usually did to look after your wellbeing have become difficult to carry on. Though you may not have control over those changes, you can focus on what choices and coping strategies you have that are within your control.

Try organizing your days to include a variety of activities that you know will improve your general mood. You can strive for a routine that is a balance of activities that give you feelings of pleasure, achievement, and closeness.

You will get a sense of accomplishment when you, for instance, choose to finish a work task, complete an exercise routine, or learn to cook a new recipe. A pleasure activity may be reading a book or watching a favourite comedy show. Schedule a video call with a friend or family to feel connected.

If you feel overwhelmed or unmotivated, break tasks down to pieces that you can work on, or set a goal to work for a small chunk of time rather than having the goal to finish something all at once.

As someone with a SCI, you have likely already experienced uncertainty. It is the ‘not knowing’ how things are going to turn out that can be difficult to cope with. The coronavirus uncertainty and isolation can be particularly worrying when you have additional health care needs.

There are different levels of worry and anxiety. Anxiety is a natural emotion and worrying is common during change. Remind yourself that you will not feel this way forever and that there are things you can do to cope. Use the diagram on the left to see if you are in the ‘fear zone’ and identify specific steps you will try to move towards learning and growth zones.

It is common during times of uncertainty, like the COVID-19 pandemic, that you may notice more worry thoughts, some even leading to worst-case scenarios. The graphic below illustrates how worries can quickly escalate even from something relatively minor that you would not have recognized as being a worry trigger before.

To reduce this type of worry, the first step is to practice noticing when your thoughts are reaching a later, more catastrophic point. For instance, if you first notice a feeling of anxiety, ask yourself, “What was I just thinking?”. Step back to the event that began your worries, and ask yourself if you have reasonable evidence to believe that the initial event is likely to lead to the worst-case scenario, or whether there may be other explanations you can consider. Are you are assuming a negative outcome when the situation is actually an unknown?

Think of a strategy that may have helped you with a similar problem in the past. Make a list of things that generally help you relax and choose one that is possible to do now.

Worry becomes a problem when it stops you from living the life you want to live, or if it leaves you feeling helpless or exhausted.

Assess the impact of your worries on your life. Seek professional help if you are noticing that you are not able to carry out important roles or activities in your life because of interference from worry.

Another effective strategy is designating a specific Worry Time – schedule a time for later in the day when you allow yourself to worry as much as you feel the need to. This can be helpful in two ways:

Worry Time may be particularly effective if your worry is hypothetical or in the future (and action is not possible). The worry should be put aside, and your attention focused on a technique or activity that will distract you from your worry thoughts (re-focus on something that is in the present).

The current pandemic has brought many changes to the lives of people with SCI, and you may notice yourself having new or different concerns for your well-being. Awareness and reminders of active, positive coping strategies are especially important.

Even though there is much about the COVID-19 situation that you cannot control, you can shift your focus to what you can influence and have power over:

“With awareness and active steps, we can exercise the positive power of being able to recognize our fear and patterns of survival” (Vicki Enns, Clinical Director, Crisis & Trauma Resource Institute)

Duff, J. (2000). Coping Effectiveness Training reduces depression and anxiety following traumatic spinal cord injury. Proceedings of the British Psychological Society, 8(1): 17.

Whalley, M. & Kaur, H. (2020, March 19). Free Guide To Living With Worry And Anxiety Amidst Global Uncertainty. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytools.com/articles/free-guide-to-living-with-worry-and-anxiety-amidst-global-uncertainty/

Enns, V. (2020, May). How to Cope with Post-Traumatic Stress During COVID-19. Retrieved from: https://ca.ctrinstitute.com/blog/how-to-cope-with-post-traumatic-stress-during-covid-19/

Wilkinson, A., Meares, K., Freestones, M. (2011). CBT for worry & generalised anxiety disorder. London: Sage.

Author: SCIRE Professional Team | Reviewers: Cynthia Morin, Andrea Townson | Published: 4 August 2020 | Updated: ~

Key Questions

What we know about the risks for people with spinal cord injury (SCI) is based on how SCI and COVID-19 both affect the body.

Everyone with SCI has some level of impairment in respiratory function given how SCI weakens breathing muscles, however people with cervical and upper thoracic levels of injury may have greater impairments than those with lower thoracic levels of injury. Still, all levels of SCI above T12 have a reduced ability to both inspire air maximally and to forcefully expel air through coughing. With an impaired cough, individuals are less able to manage respiratory secretions.

People with SCI may also have a greater risk of exposure to COVID-19, as those who require assistance cannot avoid contact with caregivers.

Given that there is no current treatment for COVID-19 other than supportive care, it is best to take precautions to avoid exposure to the virus whenever possible.

• Stay hydrated to keep lung secretions thin.

• Change positions frequently, and use gravity to help clear your lungs.

• Practice deep breathing and coughing exercises to strengthen respiratory muscles.

• Eat healthy, well-balanced meals to boost your immune system.

As a wheelchair user, it is especially important to keep at least 6 feet from another person. Because your head is lower than people who are standing you may be more vulnerable to respiratory droplets. You may consider wearing eye protection when you are not able to maintain physical distancing.

Avoid using your mouth: Ask for help, especially if others are in contact with the materials.

On the following list, check off which guidelines you already practice. Determine where you can make improvements to ensure your own safety, and the safety of those around you.

Ensure someone is available to address any of your urgent needs

Wear a mask, and request that those around you also wear a mask

Have others wash their hands when they arrive and each time interacting with you

Avoid having others directly touch your face, or their own

Ask others to stay home if they are unwell (temperature >38° or 100.4°F), if they are exhibiting any symptoms of COVID-19, or if they have possibly been exposed to an unwell person

Plan backup caregivers, and prepare others who may be needed to support you in an emergency

Let sick employees who are sent home know that there is an EI sickness benefit for those forced to quarantine due to COVID-19

Read through the SCIRE Caregiver Fact-sheet

Confirm that you provider is still seeing patients, or if an online virtual health service is available. In deciding whether to attend regular medical appointments, discuss the urgency of appointments with your doctor/care provider. Some appointments if delayed can lead to serious health risks, but others can be safely postponed (especially given additional COVID exposure risks).

FAQs About COVID-19 and SCI/D with Mount Sinai’s Dr. Bryce (2020, March 30). Retrieved from: https://newmobility.com/2020/03/faqs-about-covid-19-and-sci-d/

Information for people with paraplegia about the corona virus. (2020, March 26) Retrieved from: https://iscos.org.uk/uploads/CV-19/Factsheets/ENG_SCI_and_COVID_19_information.pdf

COVID-19 Guidance for People Living with Spinal Cord Injury. (2020, March 12). Retrieved from: https://iscos.org.uk/uploads/CV-19/ENG_COVID_19_Guidance_for_People%20-%20Copy%201.pdf

Public Safety Canada and Emergency Management Ontario. (2010). Emergency Preparedness Guide for People with Disabilities/Special Needs. Retrieved from: https://getprepared.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/pplwthdsblts/pplwthdsblts-eng.pdf

Vetkasov, A. & Hoskova, B. (2014). Special Breathing Exercises in Persons with SCI and Evaluate their Effectiveness by Using X-ray of Lungs and Other Tests. Athens Journal of Sports. 1. 217-223. https://doi.org/10.30958/ajspo.1-4-1

Health and Safety in the Time of COVID-19. (2020, May 1). Retrieved from: https://newmobility.com/2020/05/covid-19-questions-answered/

COVID-19 Guidance for the SCI Community. (2020, March 19). Retrieved from: https://scimanitoba.ca

Spinal Injuries Association on SCI and Coronavirus. (2020, March 6). Retrieved from: https://spinal.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Briefing-1-SIA-briefing-on-SCI-and-Coronavirus.pdf

Maffin, J (2020, May 25) SCI and COVID-19 Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ). Retrieved from: https://sci-bc.ca/sci-and-covid-19-frequently-asked-questions-faq/

ACI-NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation (2020, March 19). Information on Coronavirus (COVID-19) for people with Spinal Cord Injury. Retrieved from: https://iscos.org.uk/uploads/CV-19/Factsheets/ENG_COVID_19_in_SCI_Factsheet_N%20-%20Copy%201.pdf

Author: SCIRE Professional Team | Reviewer: Rachael Neal | Published: 23 July 2020 | Updated: ~

In the time of COVID-19, physically distancing is necessary to limit virus transmission and to keep everyone as safe as we possibly can. However, social isolation can have serious effects on mental health for everyone, including those with spinal cord injury (SCI).

Key Points

You may want to reach out to a professional if you experience any of the following symptoms to the extent that it is concerning to you or close others:

There are direct links between mental health and physiological health. So, it is especially important at a time like this to take care of your general health. Stay mentally and physically active, have proper nutrition, hydrate well, and get enough sleep. Maintaining physical health can help serve as a buffer for emotional stress as we are more likely to feel that we have the resources to cope with stress when we are rested and eating well versus when we are tired and hungry.

Some degree of worrying at a time like this is normal, but it is important to note if your worry is excessive, or if worry thoughts are interfering with your ability to do other things.

Strategies you can employ if you are feeling worried include:

• Noticing and limiting your exposure to things that trigger your worry,

• Practice postponing your worry to a later time, and

• Relying on reputable news sources to ensure your information regarding the pandemic is up-to-date and accurate.

Setting a routine can help you maintain a sense of normalcy during the pandemic. Stick to the usual structure of your day as best as you can by eating, exercising, and sleeping at the same times that you normally would. By setting a routine, many people find that they feel have a sense of purpose and predictability that is comforting. Using structure can also encourage us to work on tasks, which can bring feelings of accomplishment, and that feeling of accomplishment is naturally rewarding.

In the digital age, there are many ways to stay connected virtually to your loved ones. Videochatting, calling, and messaging is possible through many different platforms. ForaHealthyMe SCIO: Home is an example of a virtual platform established for connecting people with SCI.

As restrictions to physical distancing are slowly relaxing, it is possible to physically meet some of your loved ones in small numbers and at a safe distance from each other (it is still important be cautious and maintain physical distancing).

A study has shown that being up-to-date with accurate health information (e.g., treatment, local outbreak situation) and taking particular precautionary measures (e.g., hand hygiene, wearing a mask) was associated with a lower psychological impact of the outbreak and lower levels of stress, anxiety, and depression. Taking recommended steps to protect your health (e.g., washing your hands, mask use) can also remind you of the strategies that are currently within your control, which can also increase your self-confidence in coping with uncertainty over time.

Most of us are currently facing challenges that we have never faced before. It is natural and encouraged that you seek help if you require assistance in any aspect of your life. Seeking help when you need it is a sign of strength and good judgment!

There are many resources you can currently access that provide information, emotional support, and advice to people with SCI. Below are a few examples of such resources.

Resources to accessBC Government COVID-19 mental health support: Virtual Mental Health Supports During COVID-19 – Province of British Columbia BC Mental Health Hotline: dial 310-6789, and do not add 604, 778 or 250 before the number. It’s free and available 24 hours a day. We also recommend: keltyskey.com/, BounceBack bouncebackbc.ca/ and a “FACE COVID” e-book that can be found at actmindfully.com.au. For good plain language information on COVID in multiple languages, visit flattenthecurve.com and for reliable data on COVID cases worldwide, visit coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. You can also check out the other resources listed on our site: scireproject.com |

Physical distancing is a necessary precaution that needs to be taken during the COVID-19 pandemic, but it can have adverse mental health effects if you do not take steps to stay socially connected. To maintain good mental health when isolation is inevitable, we recommend maintaining good physical health, managing your worry, setting a routine, staying connected with family and friends, and staying knowledgeable about the current situation.

Frank, M., Heinemann, A. and Wong, A., 2016. An Empirical Investigation of a Biopsychosocial Model of Social Isolation in Persons with Neurological Disorders. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 97(10), p.e20.

Brooks, S., Webster, R., Smith, L., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N. and Rubin, G., 2020. The Psychological Impact of Quarantine and How to Reduce It: Rapid Review of the Evidence. SSRN Electronic Journal, 395(10227).

Migliorini C, Tonge B, Taleporos G. Spinal cord injury and mental health. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2008;42(4):309‐314. doi:10.1080/00048670801886080

Mayoclinic.org. 2020. Mental Health: What’s Normal, What’s Not – Mayo Clinic. [online] Available at: <https://mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/adult-health/in-depth/mental-health/art-20044098?p=1> [Accessed 10 June 2020].

Ohrnberger J, Fichera E, Sutton M. The relationship between physical and mental health: A mediation analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2017;195:42-49. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.11.008

Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(5):1729. Published 2020 Mar 6. doi:10.3390/ijerph17051729

What is social isolation, and what are its potential effects?

What is social isolation?

Social isolation is described as the absence of relationships, often due to physical separation from others. This differs from loneliness, which is a state of distress caused by feeling alone or separated.

Social isolation has been linked to various mental health issues, such as higher fatigue and depression rates. People who are socially isolated often report more difficulties with access and fewer close relationships.

Am I at increased risk for these potential effects if I have an SCI?

People with SCI are not necessarily more vulnerable to the effects of social isolation. However, research shows a higher proportion of depression and anxiety in people with SCI compared to the general population. The COVID-19 pandemic may limit access to caregivers or peer support networks that people with SCI depend on which can worsen symptoms of depression and anxiety.