Authors: Jaashing He, Hannah Goodings | Reviewer: Darryl Caves | Published: 7 June 2023 | Updated: ~

Key Points

- Shoulder injuries and pain are a common experience for many, with individuals with SCI having a slightly higher rate of occurrence.

- Many factors contribute to the risk of shoulder injury or shoulder pain such as age and female sex. Some factors such as strength can be improved.

- The best way to prevent shoulder injuries is to actively work to avoid them in the first place. Preventative strength training, practicing good ergonomics and improving your wheelchair handling skills can all help reduce your risk.

Shoulder pain and injury is something that many people experience, SCI or not. In the general population, 26% of people live with shoulder pain compared to 36% for SCI populations. Interestingly, when looking at the wide variation within SCI populations, there is a similar incidence of shoulder pain whether you use a powerchair, manual chair, gait-aid or no gait-aid. It is helpful to have a good understanding of what is involved in shoulder movement to understand what makes the shoulder vulnerable to injury and how best to prepare and maintain your shoulder to avoid injury.

Shoulder pain and injury is something that many people experience, SCI or not. In the general population, 26% of people live with shoulder pain compared to 36% for SCI populations. Interestingly, when looking at the wide variation within SCI populations, there is a similar incidence of shoulder pain whether you use a powerchair, manual chair, gait-aid or no gait-aid. It is helpful to have a good understanding of what is involved in shoulder movement to understand what makes the shoulder vulnerable to injury and how best to prepare and maintain your shoulder to avoid injury.

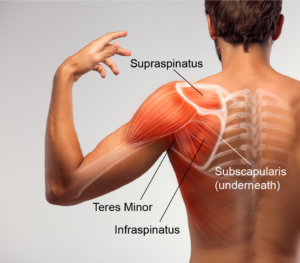

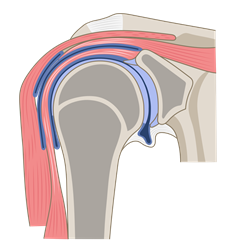

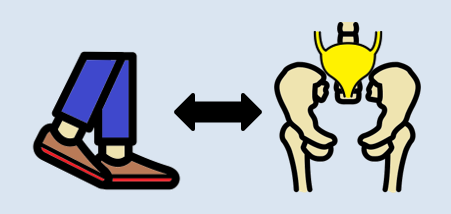

The shoulder is designed for movement and a large range of motion. Bone shape, muscle coordination and connective tissue all work together to form our most flexible joint. With this large range of movement, we sacrifice some stability. Unlike the hip joint with its “ball in cup” design giving great bony stability, the shoulder has a “ball on small plate” design. The surrounding muscles and connective tissue help keep the upper arm bone (the “ball”) in place on the shoulder blade (the “dish”). There are four muscles responsible for keeping the ball in place during movement. This group of muscles is referred to as the rotator cuff muscle group and includes the supraspinatus (above the spine of the scapula), subscapularis (on the front of the scapula), and infraspinatus (below the spine of the scapula) and teres minor (on the back of the scapula). These four small muscles are responsible for “balancing the ball” but they are not the only muscles found in the shoulder. There are larger muscles that surround the joint that are used to perform movements that involve strength such as lifting, pushing or carrying.

The shoulder is designed for movement and a large range of motion. Bone shape, muscle coordination and connective tissue all work together to form our most flexible joint. With this large range of movement, we sacrifice some stability. Unlike the hip joint with its “ball in cup” design giving great bony stability, the shoulder has a “ball on small plate” design. The surrounding muscles and connective tissue help keep the upper arm bone (the “ball”) in place on the shoulder blade (the “dish”). There are four muscles responsible for keeping the ball in place during movement. This group of muscles is referred to as the rotator cuff muscle group and includes the supraspinatus (above the spine of the scapula), subscapularis (on the front of the scapula), and infraspinatus (below the spine of the scapula) and teres minor (on the back of the scapula). These four small muscles are responsible for “balancing the ball” but they are not the only muscles found in the shoulder. There are larger muscles that surround the joint that are used to perform movements that involve strength such as lifting, pushing or carrying.

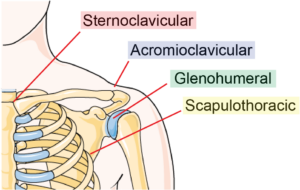

Though we often think of the shoulder as a singular joint, there are actually four joints and articulations within the shoulder system.

The joints/articulations are:

- Sternoclavicular joint (sternum and collar bone)

- Acromioclavicular (shoulder blade and collar bone)

- Glenohumeral joint (shoulder blade and upper arm)

- Scapulothoracic (ribcage and shoulder blade)

Shoulders do not work in isolation. The bones, muscles and connective tissue all interact with surrounding regions of the body resulting in the potential for disruptions in movement patterns in the shoulder. For example, the shape of the ribcage can also impact shoulder movement. It is what the shoulder blade slides on to allow for movement of the arm above shoulder height. If the shoulder blade cannot move smoothly over the ribs, reaching above shoulder height may become difficult and painful.

Shoulder pain can be grouped into two categories: neuropathic (nerve) pain and mechanical (muscle, joint and bone) pain and their treatments are different.

Neuropathic pain results from disease or damage to the nervous system (brain, spinal cord and/or nerves). This pain is often described as pins and needles, shooting electrical sensations, stabbing, coldness, burning and increased sensitivity.

Mechanical pain is related to pain from damaged joints (blue), bones (grey) or muscles (pink).4

Mechanical pain is pain that occurs when tissues (bone, joint, ligament, tendon, muscle) are pushed beyond the load they can handle, also known as exceeding their tissue capacity. This can be from a sudden event or misuse (overuse, repetitive) of the shoulder and can lead to damage of these tissues resulting in pain or injury. Tissue capacities can become more resilient with increased strength and movement training. They can also become less resilient with disuse, aging, or metabolic conditions such as poorly managed diabetes. A large decrease in activity for the shoulder can lead to decreased tissue capacity and can result in a higher likelihood for injuries and pain.

Mechanical pain can help guide us to understand when a tissue may be near its capacity and our activities should be adjusted to allow for rest and recovery. Sometimes pain will continue despite rest and become an unhelpful signal.

Refer to our article on Pain for more information!

Identifying the type (neuropathic vs. mechanical) and cause of shoulder pain can be complicated. As shoulders can be affected and affect many regions of the body, a thorough examination of the medical history and a physical examination, conducted by a health professional, is needed to best uncover the cause of pain. This thorough examination may involve:

A detailed history, including:

- Diagnosis (if this pain is a result of an injury or previous diagnosis)

- Pain history

- Occupation

- Recreational activities

- Equipment history and usage

A physical examination of the:

- Neck

- Spine

- Ribcage

- Shoulder joints

- Arm

- Posture

- Position of the shoulder blade on the ribcage

- Range of movement and strength

There are certain risk factors that increase your likelihood of developing shoulder injury or pain. Many of these risk factors also exist for the general population but there are some risk factors specific to the SCI population. Some of these factors can be changed and some cannot.

Non-modifiable risk factors for all populations

Non-modifiable factors are things that can increase risk of shoulder injuries but cannot inherently be changed. These include:

- Higher age

- Being female

- Prior shoulder injury

- Metabolic diseases leading to poor connective tissue capacity (e.g. diabetes, vascular diseases)

Non-modifiable risk factors specific to SCI

- Higher level and complete injury

- Longer duration of injury

- Muscle imbalances due to paralysis of specific muscles

- Reduced functional strength around the joint due to SCI-related muscle weakness/paralysis

- Relying heavily on upper body movement for everyday life tasks

- Postural issues due to SCI-related muscle weakness/paralysis

Risk Factors: Tetraplegia vs ParaplegiaWhile shoulder pain is more common in persons with tetraplegia and in those with complete injuries (Dyson-Hudson 2004), the cause of that shoulder pain can differ:

|

Modifiable risk factors for all populations

Modifiable factors are things that may be able to be changed with lifestyle adjustment. The risk for shoulder injury can be reduced by:

- Improving shoulder flexibility or range of movement deficit.

- Increasing shoulder muscle strength and/or balance.

- Improving posture, especially of shoulders hunched forward which can increase impingement.

- Reducing occupational exposure: percentage of time spent working at or above shoulder height, high loads or force demands, repetitive tasks, exposure to vibration, sustained or awkward postures.

Modifiable risk factors specific to SCI

- Reduce spasticity

- Reduce body weight if obese

- Improve balance or stability of the body for upper extremity tasks

- Improve home or workplace set-up to reduce shoulder height movements and weight transfers without equipment support

It is important to note that some of the factors within the modifiable lists may actually be non-modifiable for some individuals.

Refer to our article on Spasticity for more information!

Having had a shoulder injury is one of the main predictors of shoulder pain or subsequent shoulder injury. With this in mind, preventing an initial shoulder injury should be a priority.

If a shoulder injury does occur, the treatment should focus on decreasing pain and beginning initial rehabilitation followed by continued rehabilitation and prevention of future shoulder injuries.

Rehabilitation from an incident of shoulder pain or shoulder injury can seem to follow the same pathway as when one initially undergoes rehabilitation for an SCI. This is because of the need to restore and maintain mobility and strength to enable tissue capacity for function, to do the things you want and need to do. At the same time, we need to continually evaluate and re-evaluate our lifestyle, environment, and equipment choices as we age and change to ensure that these variables remain optimized and if not to change them. The following represent the key variables that need to be addressed in all situations:

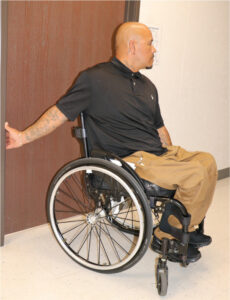

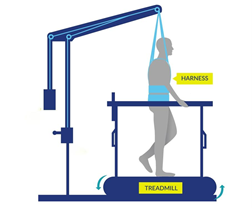

Using a propulsion assist device can eliminate the use of the arms for propulsion on a manual wheelchair.6

Managing pain

Rest and Activity Modification

Following a shoulder injury or the onset of pain, rest is often recommended as the first step in recovery. However, it can be difficult for manual wheelchair users or mobility aid users to fully rest their shoulders. In this case, you may be advised to pick and choose when to use your arms and when to use assistive technology. For example, for a manual wheelchair user, the use of a power-assisted add-on or adding a powered front-mounted system may reduce the use of the shoulders significantly.

Refer to our article on Propulsion Assist Devices for more information!

Rehabilitation techniques

Physical and occupational therapists can be great resources for injury assessments as well as pain reduction treatments and therapies. The focus of shoulder recovery should revolve around building tissue capacity through strength and flexibility training and increasing variability in movements.

Pharmacological

Medications can be used to relieve pain and allow for more movement. These pharmacological interventions include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, muscle relaxants, local anesthetic and corticosteroid injections.

Prevention and Rehabilitation

To best prevent subsequent shoulder injuries and to reduce shoulder pain, continued rehabilitation as well as strategies to reduce shoulder strain should be used.

Exercise and Stretching

Exercise programs and stretches, prescribed by a medical professional, to strengthen the shoulders, neck, chest and back muscles are helpful in preventing shoulder injuries.

The following exercises are recommended for shoulder pain after SCI, beginning with shoulder stretches and rotator cuff muscle strengthening and then other shoulder stabilizers as the pain decreases:

|

Bilateral stretch of anterior shoulder structures with “open book” stretch.7 |

Seated stretch of anterior shoulder using a doorway.8 |

|

External rotators can be strengthened using resistive bands with the elbow pressed against the body.9 |

The safest and most effective exercise to strengthen the supraspinatus muscle involves lifting the hand to shoulder height (90 degrees) diagonally (between directly in front and to the side- the scapular plane) with the thumb up (glenohumeral external rotation).10 |

|

Scapular retractors strengthening using a rowing exercise with the elbow down.11 |

Strengthening of the scapular protractors with the opposite motion, pushing forward.12 |

Thoracohumeral depressors strengthening with resisted adduction exercises (pull-down with the elbow no higher than the shoulder).13 |

Ergonomically Sound Environments

Wheelchair users and mobility-aid users are exposed frequently to environments with above-shoulder-height movements because typical environments are not adapted for their mobility needs. This is a common and often distressing issue that many people living with SCI experience. An important component of a preventative injury strategy is to arrange your work, home, and other frequented spaces in an ergonomically sound set-up style to suit your needs. A physical therapist, occupational therapist or care team can evaluate your environment to create a space that reduces effort and pain for you. Modifications may include lowering shelves to avoid raising arms above the head or arranging the storage of items so that the most frequently used objects are easier to access. Having an ergonomically sound set-up that allows you to move and function efficiently and safely is a valuable tool in preventing shoulder pain.

Refer to our article on Housing for more information!

Posture and wheelchair setup

Posture and wheelchair setup

Posture has a major impact on how the body moves and should be considered when addressing a shoulder injury or the onset of shoulder pain.

Sitting

When sitting upright, your head and back should be aligned. Hunched shoulders with a forward head can increase impingement of shoulder structures. Be aware of your sitting posture in your wheelchair by regularly looking at your posture with a camera or in the mirror. People with SCI are at risk for postural issues especially if they have some paralysis of trunk and/or upper limb muscles. This shift in posture can cause issues with the shoulder blade sliding as the arm is raised above shoulder height. If posture problems develop, request a seating review from health professionals.

Sleeping

When sleeping, ensure your shoulders are well supported. If you sleep on your side, do not lay directly on the shoulder. Pull it forward and lie on the shoulder blade. If a comfortable position cannot be found, consult your OT or PT to find an alternate technique.

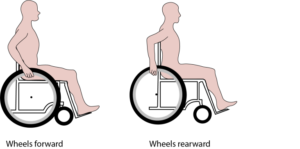

Wheelchair setup

Changes can be made to your wheelchair to help improve shoulder pain. It is important to make sure your wheelchair is set up in the most efficient way for your propulsion. Adjustment of your position in the chair as well as how the wheel is positioned will alter how you are pushing the chair, and how much energy is required to propel. Some possible adjustments include moving the rear wheel forward to reduce the reaching distance to the wheel, adjusting the wheel axle height to optimize your elbow angle (between 100-120 degrees), and general wheelchair maintenance (e.g, tire pressure, caster functions) to ensure your wheelchair remains easy to propel.

Changes can be made to your wheelchair to help improve shoulder pain. It is important to make sure your wheelchair is set up in the most efficient way for your propulsion. Adjustment of your position in the chair as well as how the wheel is positioned will alter how you are pushing the chair, and how much energy is required to propel. Some possible adjustments include moving the rear wheel forward to reduce the reaching distance to the wheel, adjusting the wheel axle height to optimize your elbow angle (between 100-120 degrees), and general wheelchair maintenance (e.g, tire pressure, caster functions) to ensure your wheelchair remains easy to propel.

Refer to our articles on Wheelchair Seating and Manual Wheelchairs for more information!

Wheelchair Skills

Increasing wheelchair skills by learning correct propelling and maneuvering techniques will aid in protecting against shoulder injuries. This includes skills such as wheelies, propulsion techniques such as using long, smooth strokes and recognizing signs that your wheelchair may need maintenance.

Refer to our article on Wheelchair Provision for more information!

Shoulder injuries are a common experience for many people. Prevention is the best approach and there are many factors that can be modified to reduce your risk of shoulder pain. These include stretching and strengthening your shoulder muscles, ensuring good posture, ergonomic assessments and bettering your wheelchair handling skills.

If you are experiencing shoulder pain or have injured your shoulder, please seek advice from your health care team. It is best to discuss all treatment options with your health providers to find out which treatments are suitable for you. For a review of how we assess evidence at SCIRE Community and advice on making decisions, please see SCIRE Community Evidence.

Parts of this page have been adapted from the SCIRE Professional “Pain Management”, “Upper Limb”, and “Wheeled Mobility and Seating Equipment” Modules:

Mehta S, Teasell RW, Loh E, Short C, Wolfe DL, Hsieh JTC (2014). Pain Following Spinal Cord Injury. In Eng JJ, Teasell RW, Miller WC, Wolfe DL, Townson AF, Hsieh JTC, Connolly SJ, Noonan VK, Loh E, McIntyre A, editors. Spinal Cord Injury Research Evidence. scireproject.com/evidence/pain-management/

Harnett A, Rice D, McIntyre A, Mehta S, Iruthayarajah I, Benton B, Teasell RW, Loh E. (2019). Upper Limb Rehabilitation Following Spinal Cord Injury. In Eng JJ, Teasell RW, Miller WC, Wolfe DL, Townson AF, Hsieh JTC, Connolly SJ, Noonan VK, Loh E, Sproule S, McIntyre A, Querée M, editors. Spinal Cord Injury Research Evidence. scireproject.com/evidence/upper-limb/

Titus L, Moir S, Casalino A, McIntyre A, Connolly S, Mortenson B, Guilbalt L, Miles S, Trenholm K, Benton B, Regan M. (2016). Wheeled Mobility and Seating Equipment Following Spinal Cord Injury. In Eng JJ, Teasell RW, Miller WC, Wolfe DL, Townson AF, Hsieh JTC, Connolly SJ, Loh E, McIntyre A, editors. Spinal Cord Injury Research Evidence. scireproject.com/evidence/wheeled-mobility-and-seating-equipment/

References

Bossuyt, F. M., Arnet, U., Brinkhof, M. W. G., Eriks-Hoogland, I., Lay, V., Müller, R., Sunnåker, M., & Hinrichs, T. (2018). Shoulder pain in the Swiss spinal cord injury community: prevalence and associated factors. Disability and Rehabilitation, 40(7), 798–805. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2016.1276974

Hodgetts, C. J., Leboeuf-Yde, C., Beynon, A., & Walker, B. F. (2021). Shoulder pain prevalence by age and within occupational groups: a systematic review. In Archives of Physiotherapy (Vol. 11, Issue 1). BioMed Central Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40945-021-00119-w

Jain, N. B., Higgins, L. D., Katz, J. N., & Garshick, E. (2010). Association of shoulder pain with the use of mobility devices in persons with chronic spinal cord injury. PM and R, 2(10), 896–900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.05.004

Dyson-Hudson, T. A., & Kirshblum, S. C. (2016). Shoulder Pain In Chronic Spinal Cord Injury, Part 1: Epidemiology, Etiology, And Pathomechanics. Http://Dx.Doi.Org/10.1080/10790268.2004.11753724, 27(1), 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790268.2004.11753724

Pannek, J., Pannek-Rademacher, S., & Wöllner, J. (2015). Use of complementary and alternative medicine in persons with spinal cord injury in Switzerland: a survey study. Spinal Cord 2015 53:7, 53(7), 569–572. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.21

Kim, E., & Kim, K. (2015). Effect of purposeful action observation on upper extremity function in stroke patients. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 27(9), 2867–2869. https://doi.org/10.1589/JPTS.27.2867

Carlson, M. J., & Krahn, G. (2009). Use of complementary and alternative medicine practitioners by people with physical disabilities: Estimates from a National US Survey. Https://Doi.Org/10.1080/09638280500212062, 28(8), 505–513. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280500212062

Image credits

- Sore shoulder ©Gan Khoon Lay, CC BY 3.0

- Modified from: Man view from back. Blades, shoulder and trapezoid illustration. Shutterstock

- Humerus Fracture ©Servier Medical Art, CC BY 3.0

- Coronal section of the shoulder joint ©Database center for life science, CC BY 4.0

- Pulley Row by SCIRE Community

- Firefly Electric Attachable Handcycle for Wheelchair © Rio Mobility 2020

- – 13. Reprinted with permission from Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation, American Spinal Injury Association. Sara J. Mulroy et al. (2020). A Primary Care Provider’s Guide to Shoulder Pain After Spinal Cord Injury. 26(3): 186–196.

- Wheelchair disability injured disabled handicapped ©stevepb, Pixabay License

- Axle Position by SCIRE Community

Posture and wheelchair setup

Posture and wheelchair setup

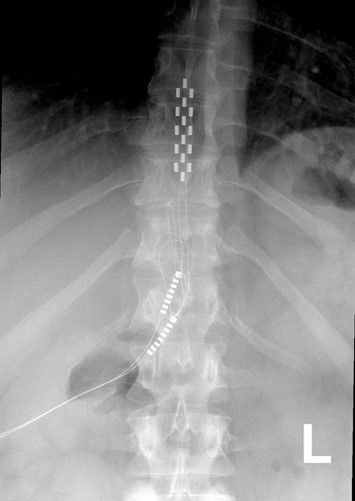

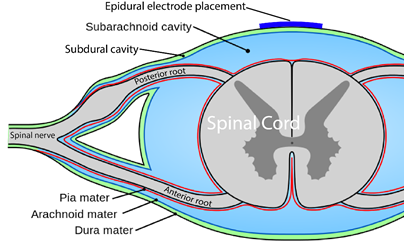

You are probably familiar with the term “epidural” already, as it is often mentioned in relation to childbirth. If a new mother says she had an epidural, what she usually means is that she had pain medication injected into the epidural space for the purpose of managing pain during birth.

You are probably familiar with the term “epidural” already, as it is often mentioned in relation to childbirth. If a new mother says she had an epidural, what she usually means is that she had pain medication injected into the epidural space for the purpose of managing pain during birth.

One of the consequences of SCI is the loss of muscle mass below the injury and a tendency to accumulate fat inside the abdomen (abdominal fat or visceral fat) and under the skin (subcutaneous fat). These changes and lower physical activity after SCI increase the risk for several diseases.

One of the consequences of SCI is the loss of muscle mass below the injury and a tendency to accumulate fat inside the abdomen (abdominal fat or visceral fat) and under the skin (subcutaneous fat). These changes and lower physical activity after SCI increase the risk for several diseases. The first use of epidural stimulation was as a treatment for

The first use of epidural stimulation was as a treatment for  Using epidural stimulation to improve respiratory function is useful because it contracts the

Using epidural stimulation to improve respiratory function is useful because it contracts the  In another study with two middle-aged females 5-10 years post-injury, one reported no change in sexual function and the other reported the ability to experience orgasms with epidural stimulation, which was not possible since her injury.

In another study with two middle-aged females 5-10 years post-injury, one reported no change in sexual function and the other reported the ability to experience orgasms with epidural stimulation, which was not possible since her injury.

In a study with a single participant (

In a study with a single participant (

In severe SCI, individuals may suffer from chronic low blood pressure and

In severe SCI, individuals may suffer from chronic low blood pressure and  For individuals with

For individuals with  Being able to control your trunk (or torso) is important for performing everyday activities such as picking things up or reaching for items. One study found that using epidural stimulation can increase the amount of distance you are able to lean forward. The improvement in forward reach occurred immediately when the stimulation was turned on. The two participants in this study were also able to reach more side to side as well, but the improvement was minor.

Being able to control your trunk (or torso) is important for performing everyday activities such as picking things up or reaching for items. One study found that using epidural stimulation can increase the amount of distance you are able to lean forward. The improvement in forward reach occurred immediately when the stimulation was turned on. The two participants in this study were also able to reach more side to side as well, but the improvement was minor.

Some studies have also found that with extensive practice (e.g., 80 sessions), independent standing (i.e., standing without the help of another person, but holding onto a bar) may be achieved without epidural stimulation. Gaining the ability to stand may also occur with stand training combined with epidural stimulation. However, the findings with regard to the effect of stand training with epidural stimulation have been mixed. For example, one study showed that stand training for 5 days a week over a 4 month period with epidural stimulation resulted in independent standing for up to 10 minutes in an individual with a complete C7 injury, while another study has suggested that independent standing for 1.5 minutes can be achieved with epidural stimulation and 2 weeks of non-step specific training in an individual with complete T6 injury.

Some studies have also found that with extensive practice (e.g., 80 sessions), independent standing (i.e., standing without the help of another person, but holding onto a bar) may be achieved without epidural stimulation. Gaining the ability to stand may also occur with stand training combined with epidural stimulation. However, the findings with regard to the effect of stand training with epidural stimulation have been mixed. For example, one study showed that stand training for 5 days a week over a 4 month period with epidural stimulation resulted in independent standing for up to 10 minutes in an individual with a complete C7 injury, while another study has suggested that independent standing for 1.5 minutes can be achieved with epidural stimulation and 2 weeks of non-step specific training in an individual with complete T6 injury. Earlier research has found that epidural stimulation can help with the development of walking-like movements, but these movements do not resemble “normal” walking. Instead, they resemble slight up and down movements of the leg. Recent studies have shown that with 10 months of practicing activities while lying down on the back and on the side, in addition to standing and stepping training, people are able to take a step without assistance from another person or body weight support. While some individuals in these studies have been able to regain some walking function, they are walking at a very slow pace, ranging from 0.19 meters per second to 0.22 meters per second. This is much slower than the 0.66 meters per second required for community walking. For example, of the 4 participants in one study, two were able to walk on the ground with a walker, one was only able to walk on a treadmill, and one was able to walk on the ground while holding the hands of another person. These differences in walking abilities gained by participants were not expected.

Earlier research has found that epidural stimulation can help with the development of walking-like movements, but these movements do not resemble “normal” walking. Instead, they resemble slight up and down movements of the leg. Recent studies have shown that with 10 months of practicing activities while lying down on the back and on the side, in addition to standing and stepping training, people are able to take a step without assistance from another person or body weight support. While some individuals in these studies have been able to regain some walking function, they are walking at a very slow pace, ranging from 0.19 meters per second to 0.22 meters per second. This is much slower than the 0.66 meters per second required for community walking. For example, of the 4 participants in one study, two were able to walk on the ground with a walker, one was only able to walk on a treadmill, and one was able to walk on the ground while holding the hands of another person. These differences in walking abilities gained by participants were not expected.

In Canada, the cost for an institution to install an epidural stimulation system for back pain in those without spinal cord injury, which is a common procedure, was $21,595 CAD. The cost incurred by a Canadian citizen undergoing implantation in Canada is $0 as it is covered by publicly funded health care.

In Canada, the cost for an institution to install an epidural stimulation system for back pain in those without spinal cord injury, which is a common procedure, was $21,595 CAD. The cost incurred by a Canadian citizen undergoing implantation in Canada is $0 as it is covered by publicly funded health care.