Authors: Dominik Zbogar and Sharon Jang | Reviewer: Susan Harkema | Published: 14 February 2022 | Updated: ~

Key Points

- Epidural stimulation is a treatment that sends electrical signals to the spinal cord.

- Epidural stimulation requires a surgical procedure to implant electrodes close to the spinal cord.

- One of the ways epidural stimulation works is by replacing the signals that would normally be sent from the brain to the spinal cord before spinal cord injury (SCI).

- Epidural stimulation affects numerous systems. Stimulation aimed at activating leg muscles may potentially also affect bowel, bladder, sexual, and cardiovascular function.

- Studies of epidural stimulation in spinal cord injury (SCI) generally do not include a comparison group without stimulation. The benefits of epidural stimulation that have been reported have been in small numbers of participants. So, while reports thus far are encouraging, more research is necessary.

- Because it is in the research and development phase, epidural stimulation for spinal cord injury is not part of standard care nor is it a readily available treatment.

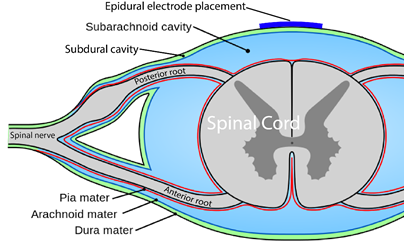

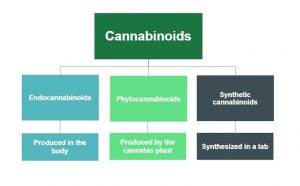

Neuromodulation is a general term for any treatment that changes or improves nerve pathways. Different types of neuromodulation can work at different sites along the nervous system (e.g., brain, nerves, spinal cord) and may or may not be invasive (i.e., involve surgery). Epidural stimulation (also known as epidural spinal cord stimulation or direct spinal cord stimulation) is a type of invasive neuromodulation that stimulates the spinal cord using electrical currents. This is done by placing an electrode on the dura (the protective covering around the spinal cord).

To read more about other types of neuromodulation used in SCI, access these SCIRE Community articles: Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES), Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS), sacral nerve stimulation, and intrathecal Baclofen.

|  |

|  |

Watch our neuromodulation series videos! Our experts explainexperimental to more commonplace applications, and individuals with SCI describe how neuromodulation has affected their lives.

What is “an Epidural”?

Epi- is a prefix and means “upon”, and the dura (full name: dura mater) is a protective covering of the spinal cord. So epidural means “upon the dura”, and in the context of epidural stimulation, this is where the electrodes that stimulate the spinal cord are placed. Yes, it is also possible to have sub-dural (under the dura) or endo-dural (within the dura) electrode placement. And, there are more layers between the dura and the spinal cord, not to mention the spinal cord itself where electrodes could be placed in what is called intraspinal microstimulation. The benefit of being beneath the dura and closer to the spinal cord is that there is a more direct stimulation. Having the electrode closer to the spinal cord allows more precision with the signal going more directly to the neurons.

The drawback is that more complications can arise with closer placement because the electrodes are in the spinal cord tissue. Such placement is currently rare, experimental, or non-existent but that will change as the technology advances. Intraspinal microstimulation has been tested in animal models and is in the process of being translated to humans.

You are probably familiar with the term “epidural” already, as it is often mentioned in relation to childbirth. If a new mother says she had an epidural, what she usually means is that she had pain medication injected into the epidural space for the purpose of managing pain during birth.

You are probably familiar with the term “epidural” already, as it is often mentioned in relation to childbirth. If a new mother says she had an epidural, what she usually means is that she had pain medication injected into the epidural space for the purpose of managing pain during birth.

We specifically discuss epidural spinal cord stimulation in this article. Spinal cord stimulation can also be applied transcutaneously. This type of spinal cord stimulation is non-invasive as the stimulating electrodes are placed on the skin. With transcutaneous stimulation, the signal has to travel a greater distance through muscle, fat, and other tissues, which means the ability to be precise with stimulation is hampered. However, it does allow for more flexibility in electrode placement and does not require surgery. There is research published or underway investigating the impact of transcutaneous stimulation in some of the areas discussed above, including hand, leg, and cardiovascular function.

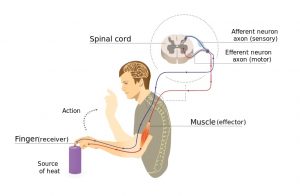

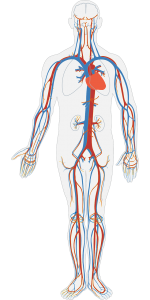

Normally, input from your senses travels in the form of electrical signals through the nerves, up the spinal cord, and reaches the brain. The brain then tells the muscles or organs what to do by sending electrical signals back down the spinal cord. After a spinal cord injury, this pathway is disrupted, preventing electrical signals from traveling below the level of injury to reach where they need to go. However, the nerves, muscles, and organs can still respond below the injury to electrical signals.

Epidural stimulation works by helping the network of nerves in the spinal cord below the injury function better and take advantage of any leftover signals from the spinal cord. To do so, the stimulation must be fine-tuned to make sure the amount of stimulation is optimal for each person and a specific function, such as moving the legs.

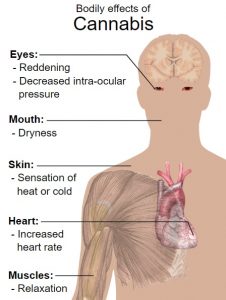

Recent studies of the role of epidural stimulation on standing and walking have noted unexpected beneficial changes in some participants’ bowel, bladder, sexual, and temperature regulation function. This highlights both the potential for epidural stimulation to improve quality of life in multiple ways and that much research remains to be done to understand how epidural stimulation affects the body.

There may still be spared connections in the spinal cord with a complete injury.

How can someone with a complete injury regain movement control with epidural stimulation?

Being assessed with a complete injury implies that there is no spared function below the injury. However, scientists are finding that this may not be the case. Studies have found that even with a complete loss of sensory and motor function, there may be some inactive connections that are still intact across the injury site. These remaining pathways may be important for regaining movement or other functions. Another hypothesis is that epidural stimulation in combination with training may encourage stronger connections across the level of injury. Although these pathways may provide some substitution for the injured ones, they are not as effective as non-injured pathways across the injury level.

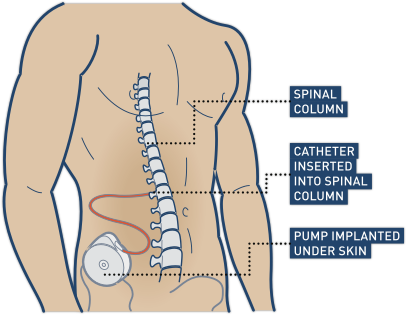

When it is decided that an individual will receive epidural stimulation, a health professional, such as a neurosurgeon, will perform an assessment of the spinal cord using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to determine the best place to implant the electrodes.

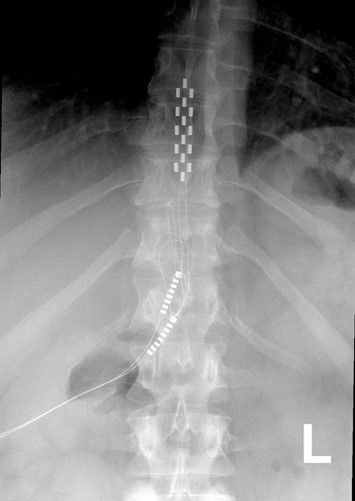

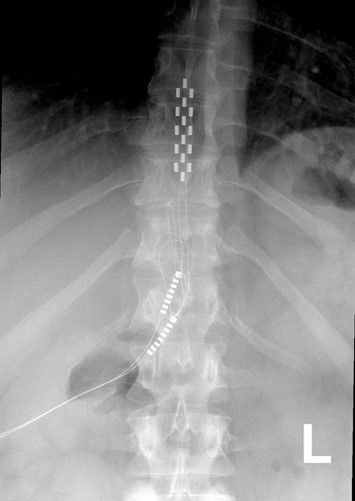

In most of the studies mentioned in this article, the electrodes were placed between the T9-L1 levels, though researchers are investigating the impact of epidural stimulation on hand function.

Xray image of wires connecting power and signal to electrodes (red circle) placed on a spinal cord.

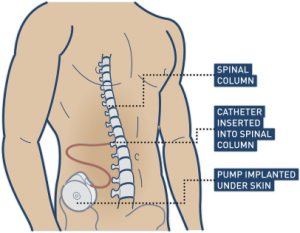

There are two possible procedures. One approach is to have two surgeries. During the initial surgery, a hollow needle is inserted through the skin into the epidural space, guided using fluoroscopy, a type of X-ray that allows the surgeon to see where the needle is in real time. Potential spots on the spinal cord are tested using a stimulator. A clinician will look to see if stimulation over those areas of the spinal cord leads to a desired response. Once found, the electrode array is properly positioned over the dura and the surgery is completed. This begins a trial period where the response to epidural stimulation is monitored. During this time the electrode array is attached to an electrical generator and power supply, which is worn on a belt outside of the body. When it is shown that things are working as desired, the generator is implanted underneath the skin in the abdomen or buttocks. The generator can be rechargeable or non-rechargeable. A remote control allows one to turn the generator on or off and control the frequency and intensity of stimulation.

The second method is to only have one surgery and no trial period. This is possible due to increased knowledge in how to stimulate the spinal cord. Soon after surgery, the individual will be taught how and when to use the epidural stimulation system at home. If needed, the frequency (how often) and intensity (how strong) of the stimulation will be adjusted at follow-up appointments with the physician. In other cases, many practice sessions of learning the right way to stimulate may be needed before a person can stimulate at home.

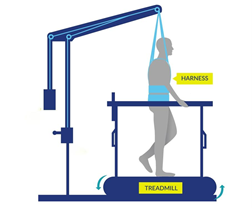

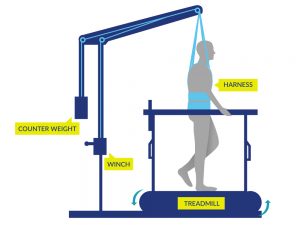

If the epidural stimulation is used for leg control, movement training, standing, and stepping will be required to learn how to coordinate and control movement during stimulation. This is required for the recovery of voluntary movements, standing and/or walking.

Epidural stimulation can be used in all people with SCI, regardless of the level or completeness of injury. However, certain situations can make it an unsafe treatment in some. It is important to speak to a health professional about your health history before beginning any new treatment.

Epidural stimulation should not be used in the following situations:

- By people with implanted medical devices like cardiac pacemakers

- By people who are unable to follow instructions or provide accurate feedback

- By people with an active infection

- By people with psychological or psychiatric conditions (e.g., depression, schizophrenia, substance abuse)

- By people who are unable to form clots (anticoagulopathy)

- Near areas of spinal stenosis (narrowing of the spinal canal)

Epidural stimulation should be used with caution in the following situations:

- By children or pregnant women

- By people who require frequent imaging tests like ultrasound or MRI (some epidural stimulation systems are compatible)

- By people using anticoagulant medications (blood thinners)

Epidural stimulation is generally well-tolerated, but there is a risk of experiencing negative effects.

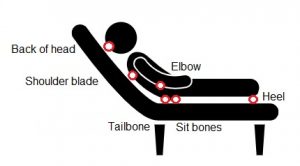

The most common risks and side effects of epidural stimulation include:

- Technical difficulties with equipment, such as malfunction or shifting of the electrodes that may require surgery to fix

- Unpleasant sensations of jolting, tingling, burning, stinging, etc. (from improper remote settings)

Other less common risks and side effects of epidural stimulation include:

- Damage to the nervous system

- Leakage of cerebrospinal fluid

- Increased pain or discomfort

- Broken bones

- Masses/lumps growing around the site of the implanted electrode

Risks specific to the surgery which involves the removal of part of the vertebral bone (laminectomy) include:

- bleeding and/or infection at the surgical site

- spinal deformity and instability

Proper training on how to use the equipment and using the stimulation according to the directions of your health provider can help decrease the risks of experiencing these side effects.

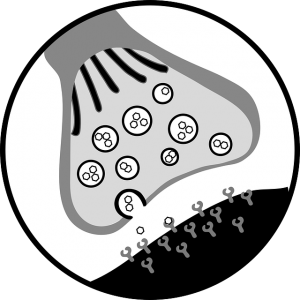

Neuromodulation methods to manage bladder function have usually involved stimulation of the sacral nerves (which are outside of the spinal cord), not with epidural spinal cord stimulation. This is reflected in the fact that almost no research exists regarding the effects of epidural stimulation on bowel and bladder function in the previous century.

Neuromodulation methods to manage bladder function have usually involved stimulation of the sacral nerves (which are outside of the spinal cord), not with epidural spinal cord stimulation. This is reflected in the fact that almost no research exists regarding the effects of epidural stimulation on bowel and bladder function in the previous century.

New information on epidural stimulation relating to bladder function is coming. In the last several years, several studies (weak evidence) from a very small group of participants of participants (who were AIS A or B) have found consistent improvements in bladder function. Participants in these reports were fitted with epidural stimulators for reactivation of paralyzed leg muscles for walking and reported additional benefits of improvements in bladder and/or bowel function. However, other studies have shown small changes to bladder function and no changes to bowel function. Negative changes, such as decreased control over the bladder, have even been noticed by some participants in another study. These findings suggest that epidural stimulation may improve quality of life by safely increasing the required time between catheterizations. Fewer catheterizations and reduced pressure in the bladder would preserve lower and upper urinary tract health. More research is required, especially with respect to bowel function. It must be noted that walk training alone has been shown to improve bladder and bowel function. Epidural stimulation may provide additional improvement to bladder function in comparison to walk training alone. Neuromodulation methods to manage bladder function have usually involved stimulation of the sacral nerves (which are outside of the spinal cord), not with epidural spinal cord stimulation. This is reflected in the fact that almost no research exists regarding the effects of epidural stimulation on bowel and bladder function in the previous century.

For more information, visit our pages on Bowel and Bladder Changes After SCI!

Why does walk/stand training alone have a beneficial effect on bladder, bowel, and sexual function?

Relationships between the leg movement and nerves in the low back regions have been identified.

Some evidence suggests that walk/step training alone can create improvements in bladder/bowel function. Researchers hypothesize that the sensory information created through walking or standing provides stimulation to the nerves in the low back region, which contains the nerves to stimulate bowel, bladder, and sexual function. Research has shown that bending and straightening the legs can be enhanced by how full the bladder is and the voiding of urine.

One of the consequences of SCI is the loss of muscle mass below the injury and a tendency to accumulate fat inside the abdomen (abdominal fat or visceral fat) and under the skin (subcutaneous fat). These changes and lower physical activity after SCI increase the risk for several diseases.

One of the consequences of SCI is the loss of muscle mass below the injury and a tendency to accumulate fat inside the abdomen (abdominal fat or visceral fat) and under the skin (subcutaneous fat). These changes and lower physical activity after SCI increase the risk for several diseases.

A single (weak-evidence) study measured body composition in four young males with complete injuries. Participants underwent 80 sessions of stand and step training without epidural stimulation, followed by another 160 sessions of stand/step training with epidural stimulation. This involved one hour of standing and one hour of stepping five days a week. After all, training was complete, all four participants had a small reduction in their body fat, and all participants but one experienced an increase in their fat free body mass (i.e., the weight of their bones, muscles, organs, and water in the body) in comparison to their initial values prior to stimulation. While all participants experienced a reduction of fat, the amount of fat loss was minimal, ranging from 0.8 to 2.4 kg over a period of a year.

The first use of epidural stimulation was as a treatment for chronic pain in the 1960s. Since then, it has been widely used for chronic pain management in persons without SCI. However, it is important to recognize that the chronic pain experienced by those without SCI is different from the chronic neuropathic pain experienced after SCI. This may explain, to some extent, why epidural stimulation has not been as successful in pain treatment for SCI. The mechanism by which electrical stimulation of the spinal cord can help with pain relief is unclear. Some research suggests that special nerve cells that block pain signals to the brain may be activated by epidural stimulation.

The first use of epidural stimulation was as a treatment for chronic pain in the 1960s. Since then, it has been widely used for chronic pain management in persons without SCI. However, it is important to recognize that the chronic pain experienced by those without SCI is different from the chronic neuropathic pain experienced after SCI. This may explain, to some extent, why epidural stimulation has not been as successful in pain treatment for SCI. The mechanism by which electrical stimulation of the spinal cord can help with pain relief is unclear. Some research suggests that special nerve cells that block pain signals to the brain may be activated by epidural stimulation.

There are a few studies focused on the role of epidural stimulation in managing pain after SCI. A number of other studies included a mix of different people with and without SCI. Because chronic neuropathic pain after SCI may not be the same as the chronic pain others experience, studies that do not separate mixed groups raise questions about the validity of findings. The number of individuals with SCI in these studies is often small, most were published in the 1980s and 1990s and so are quite dated, and the research is classified as weak evidence.

The results of this body of research show that some people may receive some pain reduction. Those who saw the most reduction in pain were individuals with an incomplete SCI. Also, satisfaction with pain reduction drops off over time. One study showed only 18% were satisfied 3 years after implantation. A different study looking at the long-term use of epidural stimulation for pain reduction found seven of nine individuals stopped using this method.

In the only recent study in this area, one woman with complete paraplegia (weak evidence) experienced a reduction in neuropathic pain frequency and intensity, and a reduction in average pain from 7 to 4 out of 10, with 0 being no pain and 10 being the worst imaginable pain. This improvement remained up to three months later after implantation of the epidural stimulation device.

It should be noted that the studies for pain place electrodes in different parts of the spinal cord compared to the more recent studies for voluntary movement, standing and stepping.

Refer to our article on Pain After SCI for more information!

Using epidural stimulation to improve respiratory function is useful because it contracts the diaphragm and other muscles that help with breathing. Also, these muscles are stimulated in a way that imitates a natural pattern of breathing, reducing muscle fatigue. More common methods of improving respiratory function do not use epidural stimulation, but rather, directly stimulate the nerves that innervate the respiratory muscles. While such methods significantly improve quality of life and function in numerous ways, they are not without issues, including muscle fatigue from directly stimulating the nerves.

Using epidural stimulation to improve respiratory function is useful because it contracts the diaphragm and other muscles that help with breathing. Also, these muscles are stimulated in a way that imitates a natural pattern of breathing, reducing muscle fatigue. More common methods of improving respiratory function do not use epidural stimulation, but rather, directly stimulate the nerves that innervate the respiratory muscles. While such methods significantly improve quality of life and function in numerous ways, they are not without issues, including muscle fatigue from directly stimulating the nerves.

To date, most research into using epidural stimulation to improve respiratory function has been done in animals. Recently, research has been done in humans and weak evidence suggests that epidural stimulation may:

- help produce a cough strong enough to clear secretions independently.

- reduce frequency of respiratory tract infections.

- reduce the time required caregiver support.

- help individuals project their voice better and communicate more effectively.

Long term use of epidural stimulation shows that improvements remain over years and that minimal supervision is needed, making it suitable for use in the community.

Refer to our article on Respiratory Changes After SCI for more information!

![]()

The impact of epidural stimulation on sexual function has been a secondary focus in research studies looking at standing and walking. Currently, there are reports from one male and two females.

![]()

After a training program of walk training with epidural stimulation, one young adult male reported stronger, more frequent erections and the ability to reach full orgasm occasionally, which was not possible before epidural stimulation. However, this study looked at the effects of walk training and epidural stimulation together, which took place after several months of walk training without stimulation. Because the researchers did not describe what the individual’s sexual function was like after walk training, it is difficult to say how much benefit is attributed to epidural stimulation versus walk training.

In another study with two middle-aged females 5-10 years post-injury, one reported no change in sexual function and the other reported the ability to experience orgasms with epidural stimulation, which was not possible since her injury.

In another study with two middle-aged females 5-10 years post-injury, one reported no change in sexual function and the other reported the ability to experience orgasms with epidural stimulation, which was not possible since her injury.

Refer to our article on Sexual Health After SCI for more information!

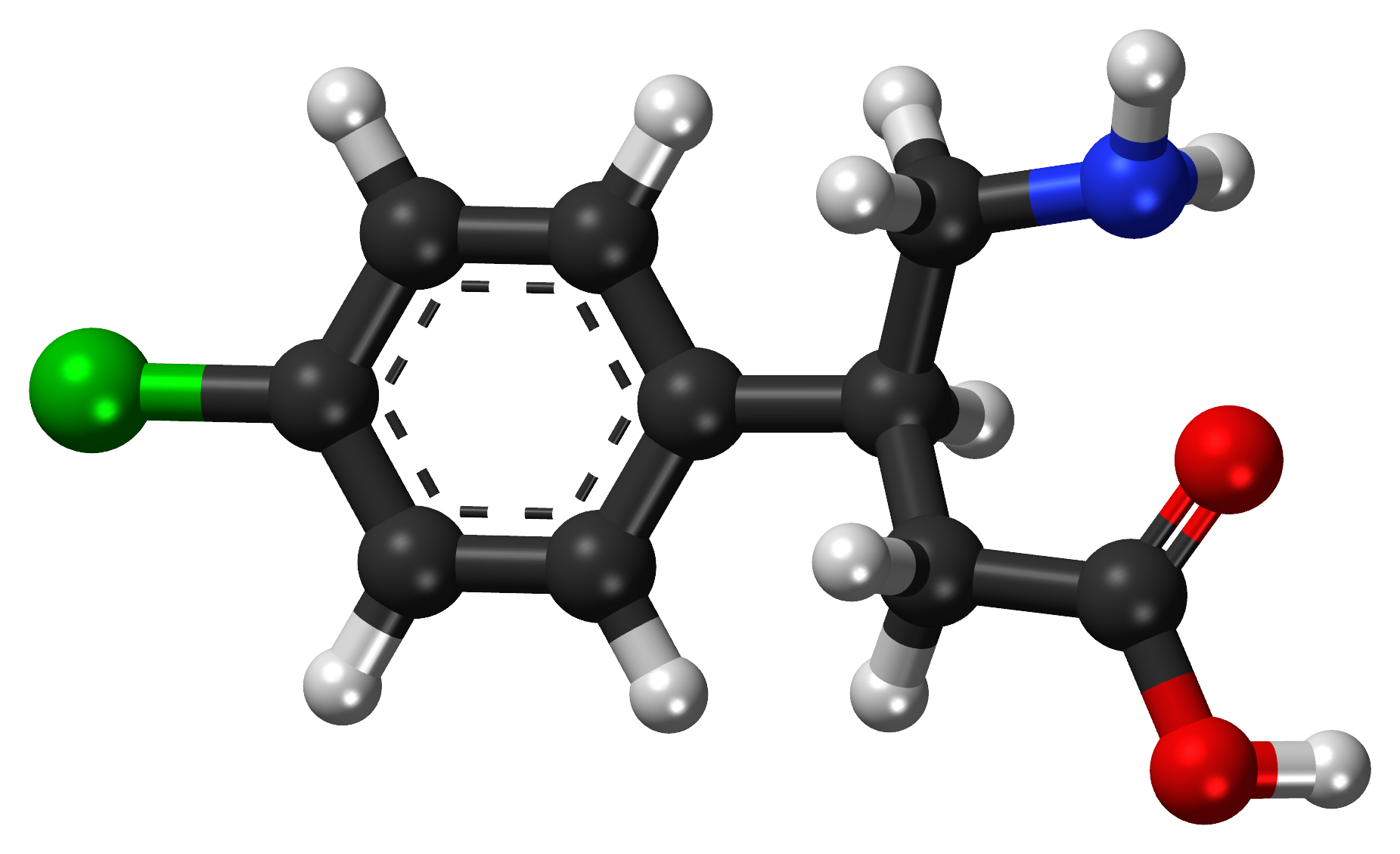

Botulinum toxin (Botox) injections and surgically implanted intrathecal Baclofen pumps are the most common ways to manage spasticity. Baclofen pumps are not without issues, however. Many individuals do not qualify for this treatment if they have seizures or blood pressure instability, and pumps require regular refilling.

Botulinum toxin (Botox) injections and surgically implanted intrathecal Baclofen pumps are the most common ways to manage spasticity. Baclofen pumps are not without issues, however. Many individuals do not qualify for this treatment if they have seizures or blood pressure instability, and pumps require regular refilling.

Research in the 80s and 90s on the use of epidural stimulation for spasticity did not report very positive findings. It was noted that greater benefits were found in those with incomplete injury compared to those who were complete. Another paper concluded that (weak evidence) the beneficial effects of epidural stimulation on spasticity may subside for most users over a short period of time. This, combined with the potential for equipment failure and adverse events, suggested that epidural stimulation was not a feasible approach for ongoing management of spasticity.

More recently, positive results with epidural stimulation have been observed (weak evidence). This is likely due to improvements in technology, electrode placement, and stimulation parameters. Positive findings show that participants:

- reported fewer spasms over 2 years

- reported a reduction in severe spasms over 2 years

- reported a reduction in spasticity

- reported an improvement in spasticity over 1 year

- were able to stop or reduce the dose of antispastic medication

For more information, visit our page on Botulinum Toxin and Spasticity!

In a study with a single participant (weak evidence) investigating walking, an individual implanted with an epidural stimulator also reported improvement in body temperature control, however details were not provided. More research is required to understand the role of epidural stimulation for temperature regulation.

In a study with a single participant (weak evidence) investigating walking, an individual implanted with an epidural stimulator also reported improvement in body temperature control, however details were not provided. More research is required to understand the role of epidural stimulation for temperature regulation.

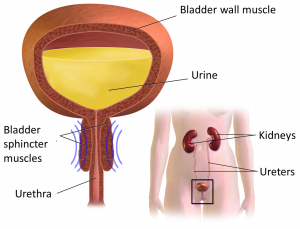

In severe SCI, individuals may suffer from chronic low blood pressure and orthostatic hypotension (fall in blood pressure when moving to more upright postures). These conditions can have significant effects on health and quality of life. Some recent studies have looked at how epidural stimulation affects cardiovascular function to improve orthostatic hypotension. Overall, they show (weak evidence) that epidural stimulation immediately increases blood pressure in individuals with low blood pressure while not affecting those who have normal blood pressure. They also showed that there is a training effect with repeated stimulation. This means that after consistently using stimulation for a while, normal blood pressure can occur even without stimulation when moving from lying to sitting.

In severe SCI, individuals may suffer from chronic low blood pressure and orthostatic hypotension (fall in blood pressure when moving to more upright postures). These conditions can have significant effects on health and quality of life. Some recent studies have looked at how epidural stimulation affects cardiovascular function to improve orthostatic hypotension. Overall, they show (weak evidence) that epidural stimulation immediately increases blood pressure in individuals with low blood pressure while not affecting those who have normal blood pressure. They also showed that there is a training effect with repeated stimulation. This means that after consistently using stimulation for a while, normal blood pressure can occur even without stimulation when moving from lying to sitting.

Moreover, researchers are starting to believe that changes in orthostatic hypotension and blood pressure can promote changes in the immune system (Bloom et al., 2020). In the body, the blood helps to circulate immune cells so they are able to fight infections in various areas. One case study found that after 97 sessions of epidural stimulation, the participant had fewer precursors for inflammation and more precursors for immune responses. Although these changes are exciting, researchers are still unsure why this happens, and whether these effects occur with all people who are implanted with an epidural stimulator.

Refer to our article on Orthostatic Hypotension for more information!

For individuals with tetraplegia, even some recovery of hand function can mean a big improvement in quality of life. Research into using epidural stimulation to improve hand function consists of one case study (weak evidence) involving two young adult males who sustained motor complete cervical spinal cord injury over 18 months prior.

For individuals with tetraplegia, even some recovery of hand function can mean a big improvement in quality of life. Research into using epidural stimulation to improve hand function consists of one case study (weak evidence) involving two young adult males who sustained motor complete cervical spinal cord injury over 18 months prior.

The researchers reported improvements in voluntary movement and hand function with training while using epidural stimulation implanted in the neck. Training involved grasping and moving a handgrip while receiving stimulation. For 2 months, one man engaged in weekly sessions while the other trained daily for seven days. One participant was tested for a longer time as a permanent electrode was implanted, while the other participant only received a temporary implant. Both participants increased hand strength over the course of one session. Additional sessions brought additional gradual improvements in hand strength as well as hand control (i.e., the ability to move the hand precisely). These improvements carried over to everyday activities, such as feeding, bathing, dressing, grooming, transferring in and out of bed and moving in bed. Notably, these improvements were maintained when participants were not using epidural stimulation.

Being able to control your trunk (or torso) is important for performing everyday activities such as picking things up or reaching for items. One study found that using epidural stimulation can increase the amount of distance you are able to lean forward. The improvement in forward reach occurred immediately when the stimulation was turned on. The two participants in this study were also able to reach more side to side as well, but the improvement was minor.

Being able to control your trunk (or torso) is important for performing everyday activities such as picking things up or reaching for items. One study found that using epidural stimulation can increase the amount of distance you are able to lean forward. The improvement in forward reach occurred immediately when the stimulation was turned on. The two participants in this study were also able to reach more side to side as well, but the improvement was minor.

Learning to make voluntary movements

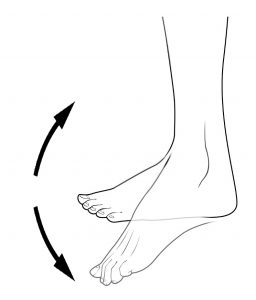

Voluntary movements (i.e., being able to move your body when you want to) of affected limbs can occur with the use of epidural stimulation. Researchers are still unsure of the right training regimen to optimize results. For example, one study found that many sessions of step training with epidural stimulation are required for participants to slowly regain voluntary movement of the leg and foot with epidural stimulation when lying down. However, another study found that participants were able to voluntarily move their legs with stimulation and no stand training.

Voluntary movements (i.e., being able to move your body when you want to) of affected limbs can occur with the use of epidural stimulation. Researchers are still unsure of the right training regimen to optimize results. For example, one study found that many sessions of step and stand training with epidural stimulation are required for participants to slowly regain voluntary movement of the leg and foot with epidural stimulation when lying down. However, another study found that participants were able to voluntarily move their legs with stimulation and no stand training though the amount each participant was able to move their legs with epidural stimulation varied greatly. For example, one participant was able to voluntarily move their leg without any stimulation after over 500 hours of stand training with epidural stimulation while another participant from the same study was not able to voluntarily move their leg without stimulation after training. Overall, more than 25 people can move some or all of their leg joints voluntarily from the first time they receive epidural stimulation.

More recently, research shows that some with epidural stimulators can produce voluntary movements without stimulation on and without any intensive training program. In one study, participants did not do a consistent intensive training program, although many of them attended out-patient therapy or did therapy at home. Over the period of a year, 3 of 7 participants were able to voluntarily bend their knee, and bend and straighten their hips. Additionally, of those 3 participants, 2 were able to point their toes up and down. While the number of people able to make voluntary movements without stimulation is small, many more studies are underway.

Recent research indicates that epidural stimulation can influence walking function in individuals with limited or no motor function. While these findings are exciting, researchers are still learning how to use stimulation effectively to produce walking motions. Before being able to walk again, people must be able to make voluntary movements and be able to stand.

Learning to stand

Some studies have also found that with extensive practice (e.g., 80 sessions), independent standing (i.e., standing without the help of another person, but holding onto a bar) may be achieved without epidural stimulation. Gaining the ability to stand may also occur with stand training combined with epidural stimulation. However, the findings with regard to the effect of stand training with epidural stimulation have been mixed. For example, one study showed that stand training for 5 days a week over a 4 month period with epidural stimulation resulted in independent standing for up to 10 minutes in an individual with a complete C7 injury, while another study has suggested that independent standing for 1.5 minutes can be achieved with epidural stimulation and 2 weeks of non-step specific training in an individual with complete T6 injury.

Some studies have also found that with extensive practice (e.g., 80 sessions), independent standing (i.e., standing without the help of another person, but holding onto a bar) may be achieved without epidural stimulation. Gaining the ability to stand may also occur with stand training combined with epidural stimulation. However, the findings with regard to the effect of stand training with epidural stimulation have been mixed. For example, one study showed that stand training for 5 days a week over a 4 month period with epidural stimulation resulted in independent standing for up to 10 minutes in an individual with a complete C7 injury, while another study has suggested that independent standing for 1.5 minutes can be achieved with epidural stimulation and 2 weeks of non-step specific training in an individual with complete T6 injury.

Learning to walk

Earlier research has found that epidural stimulation can help with the development of walking-like movements, but these movements do not resemble “normal” walking. Instead, they resemble slight up and down movements of the leg. Recent studies have shown that with 10 months of practicing activities while lying down on the back and on the side, in addition to standing and stepping training, people are able to take a step without assistance from another person or body weight support. While some individuals in these studies have been able to regain some walking function, they are walking at a very slow pace, ranging from 0.19 meters per second to 0.22 meters per second. This is much slower than the 0.66 meters per second required for community walking. For example, of the 4 participants in one study, two were able to walk on the ground with a walker, one was only able to walk on a treadmill, and one was able to walk on the ground while holding the hands of another person. These differences in walking abilities gained by participants were not expected.

Earlier research has found that epidural stimulation can help with the development of walking-like movements, but these movements do not resemble “normal” walking. Instead, they resemble slight up and down movements of the leg. Recent studies have shown that with 10 months of practicing activities while lying down on the back and on the side, in addition to standing and stepping training, people are able to take a step without assistance from another person or body weight support. While some individuals in these studies have been able to regain some walking function, they are walking at a very slow pace, ranging from 0.19 meters per second to 0.22 meters per second. This is much slower than the 0.66 meters per second required for community walking. For example, of the 4 participants in one study, two were able to walk on the ground with a walker, one was only able to walk on a treadmill, and one was able to walk on the ground while holding the hands of another person. These differences in walking abilities gained by participants were not expected.

In late 2018, one researcher demonstrated that constant epidural stimulation was interfering with proprioception, or the body’s ability to know where your limbs are in space, which ultimately hinders the walking relearning process. The solution to this problem involves activating the stimulation in a specific sequence, rather than having it continuously on. With this method and a year’s worth of training, participants were able to begin walking with an assistive device (such as a walker or poles) without stimulation. However, these individuals had to intensively practice standing and walking with stimulation for many months to produce these results. In these studies, one case of injury was reported where a participant sustained a hip fracture during walking with a body weight support. Further studies on how to individualize therapy will be necessary as the response to treatment in these studies varied greatly from person to person depending on the frequency and intensity of the stimulation.

Most of the stand/walk training conducted in the studies is with the use of a body weight support treadmill.Is it the training or the epidural stimulation?

Arm and leg movement and blood pressure have been seen to improve with epidural stimulation, but the role of rehabilitation in these recoveries is unclear. Rehabilitation techniques can have an effect on regaining motor function. For example, step/walk training alone can help improve the ability to make voluntary movements, walking and blood pressure among individuals with incomplete injuries. In much of the current research, epidural stimulation is paired with extensive training (typically around 80 sessions) before and after the epidural stimulator is implanted. Furthermore, these studies do not compare the effects of epidural stimulation to a control group who receives a fake stimulation (a placebo) which would help to see if stimulation truly has an effect. Without this comparison, we are unable to clearly understand the extent of recovery that is attributable to epidural stimulation versus the effects of training. However, evidence now shows that voluntary movement and cardiovascular function can be improved from the first time epidural stimulation is used, if the stimulation parameters are specific for the function and person, which supports the role of epidural stimulation in improving function.

Access to new medical treatment for those requiring it cannot come soon enough. Experimental therapies are typically expensive and not covered by health care. Rigorous and sufficient testing is required before treatments become standard practice and receive health care coverage. Epidural stimulation for improving function in SCI is a unique example because epidural stimulation technology has been used widely to treat intractable back pain in individuals without SCI. The benefit of this is that, if/when epidural stimulation for individuals with SCI is shown to be safe and effective, the move from experimental clinical practice could happen relatively quickly as a number of hurdles from regulatory bodies have already been overcome. That said, current barriers to accessing epidural stimulation noted in a survey study of doctors include a lack of strong evidence research showing benefits, a lack of guidelines for the right stimulation settings, and an inability to determine who will benefit from it.

In Canada, the cost for an institution to install an epidural stimulation system for back pain in those without spinal cord injury, which is a common procedure, was $21,595 CAD. The cost incurred by a Canadian citizen undergoing implantation in Canada is $0 as it is covered by publicly funded health care.

In Canada, the cost for an institution to install an epidural stimulation system for back pain in those without spinal cord injury, which is a common procedure, was $21,595 CAD. The cost incurred by a Canadian citizen undergoing implantation in Canada is $0 as it is covered by publicly funded health care.

In the United States, the cost for an institution to install an epidural stimulation system for back pain in those without spinal cord injury ranged between $32,882 USD (Medicare) and $57,896 USD (Blue Cross Blue Shield). The cost incurred for American citizens in the US will vary widely depending on their insurance coverage.

In contrast, for individuals with SCI, an epidural stimulation system is reported to cost over $100,000 USD in Thailand, and higher in other countries. Prospective clients should be aware that the epidural stimulation offered by these clinics may not be the same as that in the research reported in this article.

The recommended course for those wishing to try epidural stimulation is to register in a clinical trial. Regardless, persons interested in pursuing surgery at a private clinic or registering for clinical trials will find it useful to refer to the clinical trial guidelines published by ICORD (https://icord.org/research/iccp-clinical-trials-information/) for information on what they should be aware of when considering having an epidural stimulator implanted. Research studies that involve epidural stimulation can be found by searching the clinicaltrials.gov database.

Overall, there is evidence that epidural stimulation can improve function and health after SCI in numerous ways. However, because of the invasive nature of epidural stimulator implantation, research in this area involves few participants, no control groups, and no randomization, so it is classified as weak evidence. It is therefore important to keep in mind that while these recent reports are encouraging, more rigorous studies with more participants are needed to confirm the benefits and risks of this treatment to determine its place in SCI symptom management.

Epidural stimulation is not “plug and play” technology. Each implanted device needs to be tailored to the spine of the recipient. Some individuals respond to certain stimulation settings while others may respond better to other settings. Furthermore, over time, the need to change stimulation settings or even reposition the implant to maintain effectiveness may be required. Extensive physical training appears to be required for epidural stimulation to be most effective in improving standing or walking. The additional benefit of epidural stimulation to walk training is not always clear from the literature.

For a review of how we assess evidence at SCIRE Community and advice on making decisions, please see SCIRE Community Evidence.

Parts of this page have been adapted from the SCIRE Project (Professional) “Spasticity”, “Bladder Management”, and “Pain Management” chapters:

Hsieh JTC, Connolly SJ, McIntyre A, Townson AF, Short C, Mills P, Vu V, Benton B, Wolfe DL (2016). Spasticity Following Spinal Cord Injury. In Eng JJ, Teasell RW, Miller WC, Wolfe DL, Townson AF, Hsieh JTC, Connolly SJ, Curt A, Mehta S, Sakakibara BM, editors. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence. Version 6.0.

Available from: scireproject.com/evidence/rehabilitation-evidence/spasticity/

Hsieh J, McIntyre A, Iruthayarajah J, Loh E, Ethans K, Mehta S, Wolfe D, Teasell R. (2014). Bladder Management Following Spinal Cord Injury. In Eng JJ, Teasell RW, Miller WC, Wolfe DL, Townson AF, Hsieh JTC, Connolly SJ, Noonan VK, Loh E, McIntyre A, editors. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence. Version 5.0: p 1-196.

Available from: scireproject.com/evidence/rehabilitation-evidence/bladder-management/

Mehta S, Teasell RW, Loh E, Short C, Wolfe DL, Benton B, Hsieh JTC (2016). Pain Following Spinal Cord Injury. In Eng JJ, Teasell RW, Miller WC, Wolfe DL, Townson AF, Hsieh JTC, Connolly SJ, Loh E, McIntyre A, Querée M, editors. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence. Version 6.0: p 1-92.

Available from: scireproject.com/evidence/rehabilitation-evidence/pain-management/

Evidence for “What is epidural stimulation” is based on the following studies:

International Neuromodulation Society. (2010). Neuromodulation: An Emerging Field.

Toossi, A., Everaert, D. G., Azar, A., Dennison, C. R., & Mushahwar, V. K. (2017). Mechanically Stable Intraspinal Microstimulation Implants for Human Translation. Annals of Biomedical Engineering, 45(3), 681–694. Retrieved from http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10439-016-1709-0

Evidence for “How does epidural stimulation work?” is based on the following studies:

Evidence for “How are epidural stimulation electrodes implanted?” is based on the following studies:

Lu, D. C., Edgerton, V. R., Modaber, M., AuYong, N., Morikawa, E., Zdunowski, S., … Gerasimenko, Y. (2016a). Engaging Cervical Spinal Cord Networks to Reenable Volitional Control of Hand Function in Tetraplegic Patients. Neurorehabilitation & Neural Repair, 30(10), 951–962. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27198185

Lu, D. C., Edgerton, V. R., Modaber, M., AuYong, N., Morikawa, E., Zdunowski, S., … Gerasimenko, Y. (2016b). Engaging Cervical Spinal Cord Networks to Reenable Volitional Control of Hand Function in Tetraplegic Patients. Neurorehabilitation & Neural Repair, 30(10), 951–962.

Evidence for “Are there restrictions or precautions for using epidural stimulation?” is based on the following studies:

Moore, D. M., & McCrory, C. (2016). Spinal cord stimulation. BJA Education, 16(8), 258–263. Retrieved from https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2058534917300975

Wolter, T. (2014). Spinal cord stimulation for neuropathic pain: current perspectives. Journal of Pain Research, 7, 651–663.

Evidence for “Are there risks and side effects of epidural stimulation?” is based on the following studies:

Eldabe, S., Buchser, E., & Duarte, R. V. (2015). Complications of Spinal Cord Stimulation and Peripheral Nerve Stimulation Techniques: A Review of the Literature. Pain Medicine, 17(2), pnv025. Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/painmedicine/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/pm/pnv025

Taccola, G., Barber, S., Horner, P. J., Bazo, H. A. C., & Sayenko, D. (2020). Complications of epidural spinal stimulation: lessons from the past and alternatives for the future. Spinal Cord, 58(10), 1049–1059. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-0505-8

Evidence for “Epidural stimulation and bladder and bowel function” is based on the following studies:

Herrity, A. N., Williams, C. S., Angeli, C. A., Harkema, S. J., & Hubscher, C. H. (2018). Lumbosacral spinal cord epidural stimulation improves voiding function after human spinal cord injury. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 1–11. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-26602-2

Herrity, April N., Aslan, S. C., Ugiliweneza, B., Mohamed, A. Z., Hubscher, C. H., & Harkema, S. J. (2021). Improvements in Bladder Function Following Activity-Based Recovery Training With Epidural Stimulation After Chronic Spinal Cord Injury. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, 14(January), 1–14.

Hubscher, C. H., Herrity, A. N., Williams, C. S., Montgomery, L. R., Willhite, A. M., Angeli, C. A., & Harkema, S. J. (2018). Improvements in bladder, bowel and sexual outcomes following task-specific locomotor training in human spinal cord injury. Plos One, 1–26.

Darrow, D., Balser, D., Netoff, T. I., Krassioukov, A., Phillips, A., Parr, A., & Samadani, U. (2019). Epidural Spinal Cord Stimulation Facilitates Immediate Restoration of Dormant Motor and Autonomic Supraspinal Pathways after Chronic Neurologically Complete Spinal Cord Injury. Journal of Neurotrauma, 2336, neu.2018.6006. Retrieved from https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/neu.2018.6006

Beck, L., Veith, D., Linde, M., Gill, M., Calvert, J., Grahn, P., … Zhao, K. (2020). Impact of long-term epidural electrical stimulation enabled task-specific training on secondary conditions of chronic paraplegia in two humans. Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine, 0(0), 1–6. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/10790268.2020.1739894

Evidence for “Epidural stimulation and body composition” is based on the following studies:

Terson de Paleville, D. G. L., Harkema, S. J., & Angeli, C. A. (2019). Epidural stimulation with locomotor training improves body composition in individuals with cervical or upper thoracic motor complete spinal cord injury: A series of case studies. The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine, 42(1), 32–38.

Evidence for “Epidural stimulation and pain” is based on the following studies:

Guan, Y. (2012). Spinal cord stimulation: neurophysiological and neurochemical mechanisms of action. Current Pain and Headache Reports, 16(3), 217–225.

Marchand, S. (2015). Spinal cord stimulation analgesia. PAIN, 156(3), 364–365.

Tasker, R. R., DeCarvalho, G. T., & Dolan, E. J. (1992). Intractable pain of spinal cord origin: clinical features and implications for surgery. Journal of Neurosurgery.

Cioni, B., Meglio, M., Pentimalli, L., & Visocchi, M. (1995). Spinal cord stimulation in the treatment of paraplegic pain. Journal of Neurosurgery, 82(1), 35–39.

Warms, C. A., Turner, J. A., Marshall, H. M., & Cardenas, D. D. (2002). Treatments for chronic pain associated with spinal cord injuries: many are tried, few are helpful. Clinical Journal of Pain, 18(3), 154–163.

Reck, T. A., & Landmann, G. (2017). Successful spinal cord stimulation for neuropathic below-level spinal cord injury pain following complete paraplegia: a case report. Spinal Cord Series and Cases, 3, 17049.

Evidence for “Epidural stimulation and respiratory function” is based on the following studies:

Hachmann, J. T., Grahn, P. J., Calvert, J. S., Drubach, D. I., Lee, K. H., & Lavrov, I. A. (2017). Electrical Neuromodulation of the Respiratory System After Spinal Cord Injury. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 92(9), 1401–1414. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28781176

DiMarco, A. F., Kowalski, K. E., Geertman, R. T., & Hromyak, D. R. (2006). Spinal cord stimulation: a new method to produce an effective cough in patients with spinal cord injury. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 173(12), 1386–1389.

DiMarco, A. F., Kowalski, K. E., Geertman, R. T., & Hromyak, D. R. (2009). Lower thoracic spinal cord stimulation to restore cough in patients with spinal cord injury: results of a National Institutes of Health-sponsored clinical trial. Part I: methodology and effectiveness of expiratory muscle activation. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 90(5), 717–725.

Harkema, S. J., Wang, S., Angeli, C. A., Chen, Y., Boakye, M., Ugiliweneza, B., & Hirsch, G. A. (2018). Normalization of Blood Pressure With Spinal Cord Epidural Stimulation After Severe Spinal Cord Injury. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 12, 83.

DiMarco, A. F., Kowalski, K. E., Hromyak, D. R., & Geertman, R. T. (2014). Long-term follow-up of spinal cord stimulation to restore cough in subjects with spinal cord injury. The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine, 37(4), 380–388.

Evidence for “Epidural stimulation and sexual function” is based on the following studies:

Harkema, S., Gerasimenko, Y., Hodes, J., Burdick, J., Angeli, C., Chen, Y., … Edgerton, V. R. (2011). Effect of epidural stimulation of the lumbosacral spinal cord on voluntary movement, standing, and assisted stepping after motor complete paraplegia: A case study. The Lancet, 377(9781), 1938–1947.

Darrow, D., Balser, D., Netoff, T. I., Krassioukov, A., Phillips, A., Parr, A., & Samadani, U. (2019). Epidural Spinal Cord Stimulation Facilitates Immediate Restoration of Dormant Motor and Autonomic Supraspinal Pathways after Chronic Neurologically Complete Spinal Cord Injury. Journal of Neurotrauma, 2336, neu.2018.6006. Retrieved from https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/neu.2018.600

Evidence for “Epidural stimulation and spasticity” is based on the following studies:

Nagel, S. J., Wilson, S., Johnson, M. D., Machado, A., Frizon, L., Chardon, M. K., … Howard, M. A. 3rd. (2017). Spinal Cord Stimulation for Spasticity: Historical Approaches, Current Status, and Future Directions. Neuromodulation: Journal of the International Neuromodulation Society, 20(4), 307–321.

Dekopov, A. V., Shabalov, V. A., Tomsky, A. A., Hit, M. V., & Salova, E. M. (2015). Chronic spinal cord stimulation in the treatment of cerebral and spinal spasticity. Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery.

Dimitrijevic, M. R., Illis, L. S., Nakajima, K., Sharkey, P. C., & Sherwood, A. M. (1986). Spinal cord stimulation for the control of spasticity in patients with chronic spinal cord injury: II. Neurophysiologic observations. Central Nervous System Trauma, 3(2), 145–152. Retrieved from http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=med2&AN=3490313

Midha, M., & Schmitt, J. K. (1998). Epidural spinal cord stimulation for the control of spasticity in spinal cord injury patients lacks long-term efficacy and is not cost-effective. Spinal Cord, 36(3), 190–192. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/3100532

Barolat, G., Singh-Sahni, K., Staas, W. E. J., Shatin, D., Ketcik, B., & Allen, K. (1995). Epidural spinal cord stimulation in the management of spasms in spinal cord injury: a prospective study. Stereotactic & Functional Neurosurgery, 64(3), 153–164.

Dekopov, A. V., Shabalov, V. A., Tomsky, A. A., Hit, M. V., & Salova, E. M. (2015). Chronic spinal cord stimulation in the treatment of cerebral and spinal spasticity. Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery.

Pinter, M. M., Gerstenbrand, F., & Dimitrijevic, M. R. (2000). Epidural electrical stimulation of posterior structures of the human lumbosacral cord: 3. Control Of spasticity. Spinal Cord, 38(9), 524–531. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/3101040

Evidence for “Epidural stimulation and temperature regulation” is based on the following studies:

Edgerton, V. R., & Harkema, S. (2011). Epidural stimulation of the spinal cord in spinal cord injury: current status and future challenges. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 11(10), 1351–1353. Retrieved from http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=med7&AN=21955190

Harkema, S. J., Gerasimenko, Y., Hodes, J., Burdick, J., Angeli, C., Chen, Y., … Edgerton, V. R. (2011). Supplementary index: Effect of epidural stimulation of the lumbosacral spinal cord on voluntary movement, standing, and assisted stepping after motor complete paraplegia: A case study. The Lancet, 377(9781), 1938–1947. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21601270

Evidence for “Epidural stimulation and cardiovascular function” is based on the following studies:

Bloom, O., Wecht, J. M., Legg Ditterline, B. E., Wang, S., Ovechkin, A. V., Angeli, C. A., … Harkema, S. J. (2020). Prolonged Targeted Cardiovascular Epidural Stimulation Improves Immunological Molecular Profile: A Case Report in Chronic Severe Spinal Cord Injury. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, 14(October), 1–11.

Evidence for “Epidural stimulation and hand function” is based on the following study:

Lu, D. C., Edgerton, V. R., Modaber, M., AuYong, N., Morikawa, E., Zdunowski, S., … Gerasimenko, Y. (2016a). Engaging Cervical Spinal Cord Networks to Reenable Volitional Control of Hand Function in Tetraplegic Patients. Neurorehabilitation & Neural Repair, 30(10), 951–962. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27198185

Evidence for “Epidural stimulation and movement: trunk control” is based on the following studies:

Evidence for “Epidural stimulation and movement: voluntary movements” is based on the following studies:

Rejc, E., Angeli, C. A., Bryant, N., & Harkema, S. J. (2017). Effects of Stand and Step Training with Epidural Stimulation on Motor Function for Standing in Chronic Complete Paraplegics. Journal of Neurotrauma, 34, 1787–18023. Retrieved from www.liebertpub.com

Angeli, C. A., Edgerton, V. R., Gerasimenko, Y. P., & Harkema, S. J. (2014). Altering spinal cord excitability enables voluntary movements after chronic complete paralysis in humans. Brain, 137(Pt 5), 1394–1409. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3999714/

Peña Pino, I., Hoover, C., Venkatesh, S., Ahmadi, A., Sturtevant, D., Patrick, N., Freeman, D., Parr, A., Samadani, U., Balser, D., Krassioukov, A., Phillips, A., Netoff, T. I., & Darrow, D. (2020). Long-Term Spinal Cord Stimulation After Chronic Complete Spinal Cord Injury Enables Volitional Movement in the Absence of Stimulation. Frontiers in systems neuroscience, 14, 35. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsys.2020.00035

Evidence for “Epidural stimulation and movement: walking and standing” is based on the following studies:

Grahn, P. J., Lavrov, I. A., Sayenko, D. G., Straaten, M. G. Van, Gill, M. L., Strommen, J. A., … Lee, K. H. (2017). Enabling Task-Specific Volitional Motor Functions via Spinal Cord Neuromodulation in a Human with Paraplegia. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 92(4), 544–554. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.02.014

Harkema, S. J., Gerasimenko, Y., Hodes, J., Burdick, J., Angeli, C., Chen, Y., … Edgerton, V. R. (2011). Supplementary index: Effect of epidural stimulation of the lumbosacral spinal cord on voluntary movement, standing, and assisted stepping after motor complete paraplegia: A case study. The Lancet, 377(9781), 1938–1947. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21601270

Rejc, E., Angeli, C. A., Atkinson, D., & Harkema, S. J. (2017). Motor recovery after activity-based training with spinal cord epidural stimulation in a chronic motor complete paraplegic. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 13476. Retrieved from www.nature.com/scientificreports

Rejc, E., Angeli, C., & Harkema, S. (2015). Effects of Lumbosacral Spinal Cord Epidural Stimulation for Standing after Chronic Complete Paralysis in Humans. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource], 10(7), e0133998. Retrieved from http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=med8&AN=26207623

Grahn, P. J., Lavrov, I. A., Sayenko, D. G., Straaten, M. G. Van, Gill, M. L., Strommen, J. A., … Lee, K. H. (2017). Enabling Task-Specific Volitional Motor Functions via Spinal Cord Neuromodulation in a Human with Paraplegia. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 92(4), 544–554. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.02.014

Gill, M. L., Grahn, P. J., Calvert, J. S., Linde, M. B., Lavrov, I. A., Strommen, J. A., … Zhao, K. D. (2018). Neuromodulation of lumbosacral spinal networks enables independent stepping after complete paraplegia. Nature Medicine, 24(11), 1677–1682. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0175-7

Angeli, C. A., Boakye, M., Morton, R. A., Vogt, J., Benton, K., Chen, Y., … Harkema, S. J. (2018). Recovery of Over-Ground Walking after Chronic Motor Complete Spinal Cord Injury. New England Journal of Medicine, 379(13), 1244–1250. Retrieved from http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=medl&AN=30247091

van de Port, I. G., Kwakkel, G., & Lindeman, E. (2008). Community ambulation in patients with chronic stroke: How is it related to gait speed? Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 40(1), 23–27.

Wagner, F. B., Mignardot, J.-B., Le Goff-Mignardot, C. G., Demesmaeker, R., Komi, S., Capogrosso, M., … Courtine, G. (2018). Targeted neurotechnology restores walking in humans with spinal cord injury. Nature, 563(7729), 65–71. Retrieved from http://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-018-0649-2

Angeli, C. A., Edgerton, V. R., Gerasimenko, Y. P., & Harkema, S. J. (2014). Altering spinal cord excitability enables voluntary movements after chronic complete paralysis in humans. Brain, 137(Pt 5), 1394–1409. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3999714/

Carhart, M. R., He, J., Herman, R., D’Luzansky, S., & Willis, W. T. (2004). Epidural spinal-cord stimulation facilitates recovery of functional walking following incomplete spinal-cord injury. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems & Rehabilitation Engineering, 12(1), 32–42. Retrieved from http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=med5&AN=15068185

Harkema, S. J., Wang, S., Angeli, C. A., Chen, Y., Boakye, M., Ugiliweneza, B., & Hirsch, G. A. (2018). Normalization of Blood Pressure With Spinal Cord Epidural Stimulation After Severe Spinal Cord Injury. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 12, 83.

Legg Ditterline, B. E., Aslan, S. C., Wang, S., Ugiliweneza, B., Hirsch, G. A., Wecht, J. M., & Harkema, S. (2020). Restoration of autonomic cardiovascular regulation in spinal cord injury with epidural stimulation: a case series. Clinical Autonomic Research, (0123456789), 2–5. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s10286-020-00693-2

Evidence for “Costs and availability of epidural stimulation” is based on the following studies:

Solinsky, R., Specker-Sullivan, L., & Wexler, A. (2020). Current barriers and ethical considerations for clinical implementation of epidural stimulation for functional improvement after spinal cord injury. Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine, 43(5), 653–656.

Kumar, K., & Bishop, S. (2009). Financial impact of spinal cord stimulation on the healthcare budget: a comparative analysis of costs in Canada and the United States. Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine.

Image credits

- Image by SCIRE Community Team

- Image by SCIRE Community Team

- Image by SCIRE Community Team

- Image by SCIRE Community Team

- Adapted from image made by Mysid Inkscape, based on plate 770 from Gray’s Anatomy (1918, public domain).

- Pregnant woman holding tummy. [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)] via Google Images.

- Edited from Nervous system, Musculature. ©Servier Medical Art. CC BY 3.0.

- Neurons ©NIH Image Gallery. CC BY-NC 2.0.

- Image by SCIRE Community

- bladder by fauzan akbar from the Noun Project

- Large Intestine by BomSymbols from the Noun Project

- Feet by Matt Brooks from the Noun Project

- hip by priyanka from the Noun Project

- visceral fat by Olena Panasovska from the Noun Project

- Lightning by FLPLF from the Noun Project

- Lungs by dDara from the Noun Project

- Love by Jake Dunham from the Noun Project

- Male by Centis MENANT from the Noun Project

- Female by Centis MENANT from the Noun Project

- Image by SCIRE Community

- Temperature by Adrien Coquet from the Noun Project

- Heart by Nick Bluth from the Noun Project

- Image by SCIRE Community

- Hand by Sergey Demushkin from the Noun Project

- Torso by Ronald Vermeijs from the Noun Project

- Yoga posture by Gan Khoon Lay from the Noun Project

- Standing by Rafo Barbosa from the Noun Project

- Walking by Samy Menai from the Noun Project

- Image by SCIRE Community

- Canada by Yohann Berger from the Noun Project

- United States of America by Yohann Berger from the Noun Project

Botulinum toxin is given with an injection into the affected spastic muscle or bladder.

Botulinum toxin is given with an injection into the affected spastic muscle or bladder.

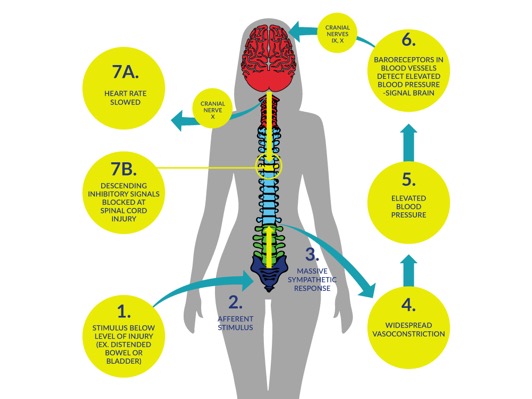

Autonomic dysreflexia can be life threatening when severe. If left untreated, uncontrolled elevated blood pressure can lead to serious conditions like stroke, heart attack, detached retinas, seizures, and even death.

Autonomic dysreflexia can be life threatening when severe. If left untreated, uncontrolled elevated blood pressure can lead to serious conditions like stroke, heart attack, detached retinas, seizures, and even death.

When the body below the SCI detects strong stimulation, it activates the sympathetic nervous system, causing the constriction of blood vessels in the lower body. This causes blood pressure to rise.

When the body below the SCI detects strong stimulation, it activates the sympathetic nervous system, causing the constriction of blood vessels in the lower body. This causes blood pressure to rise.

If the steps above do not reduce blood pressure and it remains high (150 mmHg or above), seek emergency medical attention by calling an ambulance or visiting an emergency department. Emergency medical treatments involve the use of medications that rapidly lower blood pressure. The health providers may also run a series of tests to identify the cause of the episode if one has not been found.

If the steps above do not reduce blood pressure and it remains high (150 mmHg or above), seek emergency medical attention by calling an ambulance or visiting an emergency department. Emergency medical treatments involve the use of medications that rapidly lower blood pressure. The health providers may also run a series of tests to identify the cause of the episode if one has not been found. Bladder problems are the most common triggers of autonomic dysreflexia. Methods that may be used to prevent bladder problems from triggering autonomic dysreflexia include:

Bladder problems are the most common triggers of autonomic dysreflexia. Methods that may be used to prevent bladder problems from triggering autonomic dysreflexia include: Bowel problems are another common trigger of autonomic dysreflexia. Methods that may be used to prevent bowel problems from triggering autonomic dysreflexia include:

Bowel problems are another common trigger of autonomic dysreflexia. Methods that may be used to prevent bowel problems from triggering autonomic dysreflexia include: Pressure ulcers, ingrown toenails, and burns can all be additional causes of autonomic dysreflexia. Methods that may be used to prevent skin problems from triggering autonomic dysreflexia include:

Pressure ulcers, ingrown toenails, and burns can all be additional causes of autonomic dysreflexia. Methods that may be used to prevent skin problems from triggering autonomic dysreflexia include:

There are some situations in which FES may be unsafe to use. This not a complete list, speak to a health provider about your health history and whether FES is safe for you.

There are some situations in which FES may be unsafe to use. This not a complete list, speak to a health provider about your health history and whether FES is safe for you. Studies have shown that both FES arm exercise and FES cycling helps to maintain or improve strength after SCI. However, FES cycling may be more effective for maintaining strength after injury than improving strength that has already been lost. This is supported by moderate evidence from five studies.

Studies have shown that both FES arm exercise and FES cycling helps to maintain or improve strength after SCI. However, FES cycling may be more effective for maintaining strength after injury than improving strength that has already been lost. This is supported by moderate evidence from five studies. Fifteen studies have looked at FES for improving many different aspects of fitness after SCI. Taken altogether, these studies provide weak evidence that FES training done at least 3 days per week for 2 months helps to improve many aspects of cardiovascular fitness after SCI.

Fifteen studies have looked at FES for improving many different aspects of fitness after SCI. Taken altogether, these studies provide weak evidence that FES training done at least 3 days per week for 2 months helps to improve many aspects of cardiovascular fitness after SCI. Studies show that FES improves walking speed and distance in people with both incomplete and complete SCI. Some of these studies also showed that regular use of FES carried over to improve walking even without FES. This is supported by weak evidence from eight studies.

Studies show that FES improves walking speed and distance in people with both incomplete and complete SCI. Some of these studies also showed that regular use of FES carried over to improve walking even without FES. This is supported by weak evidence from eight studies. Although it is commonly thought that increased muscle bulk from FES will reduce the risk of pressure sores, there are not very many studies which have looked at whether this actually happens. One study provides weak evidence that FES cycling for 2 years reduced the number of pressure ulcers that occurred after SCI. Another study showed that regular FES cycling showed a trend toward reducing seat pressures.

Although it is commonly thought that increased muscle bulk from FES will reduce the risk of pressure sores, there are not very many studies which have looked at whether this actually happens. One study provides weak evidence that FES cycling for 2 years reduced the number of pressure ulcers that occurred after SCI. Another study showed that regular FES cycling showed a trend toward reducing seat pressures. Research studies show that FES cycling does not prevent bone loss after SCI (moderate evidence from two studies). However, it may help to increase bone density that has already been lost, although the evidence for this is conflicting (based on six studies). It is not clear whether any gains in bone density last long-term or if continued FES treatment is needed for them to be maintained.

Research studies show that FES cycling does not prevent bone loss after SCI (moderate evidence from two studies). However, it may help to increase bone density that has already been lost, although the evidence for this is conflicting (based on six studies). It is not clear whether any gains in bone density last long-term or if continued FES treatment is needed for them to be maintained.