Author: Sharon Jang | Reviewer: Lisa Kristalovich | Published: 6 July 2022 | Updated: ~

Key Points

- After spinal cord injury (SCI), many people are still able to drive.

- In order to return to driving, an in-depth driving assessment needs to be conducted by a driving rehabilitation specialist or occupational therapist.

- There are many different types of modifications that can be made to a vehicle based on your needs and limitations.

Being able to drive is an important skill that is helpful for day-to-day activities. Research has shown that being able to drive is related to many benefits, such as:

Being able to drive is an important skill that is helpful for day-to-day activities. Research has shown that being able to drive is related to many benefits, such as:

- Improved happiness with life

- Decreased depression

- Increased access to health vehicle services in the community

- Increased engagement in daily activities, such as running errands

- A greater sense of independence

In addition, research has found that driving is associated with being able to work post-SCI. After SCI, one of the biggest barriers to working is a lack of transportation. Being able to drive on your own can address this issue, and promote working.

Many people can still drive after SCI. One study noted that many people with a C4 injury or below are able to independently drive. Although a formal driving assessment is often required before you are able to drive, some positive signs that you will be able to drive again include:

- Stable SCI – there are no changes to your function

- You don’t need narcotics to control your pain

- Good vision/corrected vision

- Controlled muscle spasms

- Ability to transfer on and off a toilet

Research also shows that tetraplegics are able to drive as well as able-bodied individuals but have slower reaction times. Nonetheless, many people with SCI are able to drive.

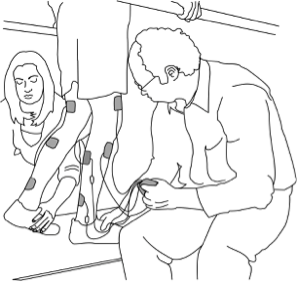

Before getting on the road again, a formal driving assessment is often done by an occupational therapist or a driving rehabilitation specialist. During these assessments, the specialist will go over your medical history, driving history, and goals for driving. In addition, they will evaluate many aspects of your health and functioning, which include the following:

Vision

The specialist will assess if you are seeing things correctly with a vision test.

Physical abilities

Many aspects of your physical abilities will be assessed, including:

- The strength and amount of movement in your limbs for controlling the vehicle

- How much are you able to rotate your head and neck to check for vehicles

- How quickly you are able to react to other vehicles, pedestrians, and other objects on the road (i.e., your reaction time)

- Balance, which is used for getting in and out of the vehicle and being able to sit still while making turns

- Hand-eye coordination

Cognition

Driving requires a lot of focus. Some tests will be done to evaluate how well and fast your brain is working. Some of these include:

- Memory, which can influence remembering the rules of the road and navigating the road

- Visual processing, or how fast you understand and interpret what you see happening on the road

- Visual spatial abilities, or being able to identify where things are on the road and judging their distance

- Visual perception, or your brain’s ability to make sense of what you see

- Attention, which is required for paying attention to the road

- Judgement and decision making, which are used in cases of knowing when to go/stop, when to switch lanes, etc.

Mood/behaviours

Mood and behaviours may also be evaluated during an assessment. Some traits may be red flags for driving, including being overly anxious on the road, being impulsive, and being highly irritable.

After you find out what kind of equipment you need to adapt your vehicle, you must learn to use it to drive in a safe manner. Driver rehab provides training and supervised practice using your newly modified vehicle. Some topics that may be covered in driver rehab include:

- How to use your adaptive driving equipment or perform different driving techniques

- Cognitive strategies to address issues with memory, attention, etc.

- Visual strategies to address perception, sight, etc.

- Anxiety management

- A reintroduction to the driving environment

Often, you will need to participate in driver rehab sessions until you are able to demonstrate proficiency with using your vehicle modifications under typical driving conditions. In some areas of the world, a road test may be required to get your full license.

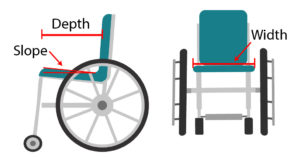

Many vehicles can be adapted for driving after SCI. However, the ideal vehicle for you is dependent on your wants and needs. For example, paraplegics tend to transfer into the driver seat of the vehicle, while among tetraplegics, half will transfer to the drivers seat and half will drive in their wheelchair. If you are driving in your wheelchair, you will need a larger vehicle to accommodate the wheelchair. However, if you are transferring into the vehicle seat, you might want a vehicle that is closer to the ground for an easier transfer and wheelchair loading. Larger vehicles like trucks and SUVs may require extra equipment to help with transfers and wheelchair loading.

One study has looked at the measurements of various vehicles. In regards to the height between the ground and the driver seat, they found that the average height is:

- 22 inches for a sedan

- 28 inches for a mid-height vehicle (vans, small-medium SUVs)

- 36 inches for a high-profile vehicle (large truck or SUV)

This study also found that the average difference in height between the driver’s seat and wheelchair seat is 3.7 inches, and ranged from -3.5 inches to 16 inches. This means that for some vehicles, the wheelchair seat may be above the vehicle seat, while in others, they can be up to 16 inches below the vehicle seat. Your ability to transfer is a consideration in what kind of vehicle to buy. Other considerations include how much space you want in your vehicle, where you will be driving your vehicle, and how/where you will be storing your wheelchair if you plan on transferring into the driver seat of the vehicle.

Collision warning braking support is available for some vehicles and can aid in collision prevention.

A vehicle can be adapted in many ways with the use of adaptive driving equipment, or technology used to make your vehicle more accessible. In general, driving is broken into 4 parts:

- transferring in and out of the vehicle

- loading your wheelchair

- using primary controls (steering, accelerating, braking)

- using secondary controls (e.g., controlling the windshield, signals, radio)

In addition, there are various safety features that can be added to the vehicle to help you drive if you have any limitations. Some driver rehabilitation centers will also complete a vehicle modification assessment. During this assessment, a driving specialist will help you select the equipment to get you and your wheelchair into the vehicle safely.

Transferring in and out of the vehicle

A ramp can be installed to allow for ease of vehicle entry/exit.

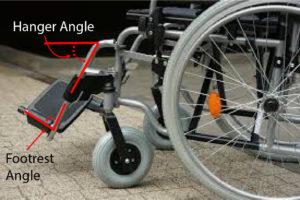

When getting in and out of your vehicle, the first consideration is whether you are able to transfer into the driver seat, or if you will stay in your wheelchair. Although it is possible to drive from your wheelchair, some additional considerations include:

- the original driver seat in the vehicle has been designed to withstand a vehicle crash, and is in an optimal position to be used with the air bag and seatbelt

- the seatbelt may not fit ideally when in your wheelchair due to the design of a wheelchair

Transferring from a manual wheelchair into the driver seat and manually loading the wheelchair

There are many ways to get into your vehicle from a wheelchair. The following is a general overview of the steps.

- Transfer into the seat. This can be done using a transfer board, hanging onto a grab bar/ handle, or placing a hand on the seat. Some people choose to transfer by placing their right leg into the vehicle before transferring, or they keep both their legs outside of the vehicle.

Decide where you will place your wheelchair: in the front passenger seat, or the back seats. Those with weaker shoulder muscles should consider loading their wheelchair into the front seats.

Decide where you will place your wheelchair: in the front passenger seat, or the back seats. Those with weaker shoulder muscles should consider loading their wheelchair into the front seats.- Remove the wheels from the wheelchair. This is commonly done by pressing the center button in the middle of the wheel. Place the tires in the vehicle.

- Some people remove the cushion and the side guard from the wheelchair. Place these in the vehicle.

- Load the wheelchair frame into the vehicle. Reclining the front seat can help you get the frame over your body and into the vehicle.

Driving from the driver seat

Swivel-style car seats can come out of the car or turn inside of the car.

If you have difficulties with transfering or loading your wheelchair there are many adaptations that can be used. Swivel seats are seats that turn and come out of the vehicle, giving you more space to transfer in. Alternatively, a transfer seat can be used. A transfer seat can move up or down in height, can turn, and can be moved in the vehicle for more space. This is done by placing the original driver seat on top of a motorized plate. However, it is important to note that swivel seats are only compatible with some SUV’s, trucks, and minivans, and transfer seats are only compatible with minivans or full sized vans. If you only need a bit of assistance getting in and out of a vehicle, additional grab bars can be installed into a vehicle.

Driving from your wheelchair

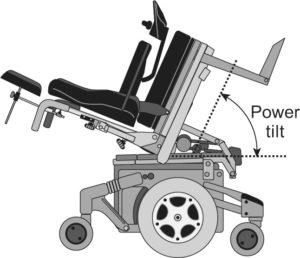

If it is decided that it is best for you to drive from your wheelchair, you will need a wheelchair accessible vehicle. To have enough height for a wheelchair to enter, the vehicle is raised up and the floor is lowered. A ramp is then installed. It may come out from the floor or fold out. Once in your vehicle, it is important to make sure that your wheelchair is stiff enough to provide a stable driving platform, and will not move when you are driving.

Wheelchair tie downs should be used to secure the wheelchair when driving.

Your wheelchair will also need to be secured in place while driving. This can be done with a manual locking system and the help of another person. There are also automated docking systems which anchors your wheelchair without the help of another person. These systems have an additional piece that connects to your wheelchair. The part on your wheelchair clicks into the docking system on the floor of your vehicle. Automated docking systems are controlled electronically. A button installed in your vehicle releases the docking system lock. The part that attaches to your wheelchair weighs 10-19 lbs, and is permanently attached to your wheelchair. Many people using a manual wheelchair have a hard time managing the extra weight on the wheelchair, so this system is usually used with power wheelchairs.

Primary Controls (steering, braking, acceleration)

To help with steering and driving, different handles can be added onto the steering wheel. A spinner knob can be added to make it easier to control the steering wheel. For people with no hand function, a tri-pin add on may be helpful. A tri-pin handle consists of one larger straight prong, and two smaller straight prongs. The larger prong sits in your hand, and your wrist sits between the two smaller prongs. This allows you to use your shoulder and elbow muscles to steer.

Rods can be connected to the accelerator and brakes to allow for hand control driving.

To accelerate and brake, rods are connected to the pedals, and the rod is connected to a handle beside the steering wheel. The handle is pushed forward to brake. Different motions, including depressing, rocking, pulling, or twisting can be used to control the gas. These hand controls are not removable, but the pedals remain in place so an able-bodied person can drive. The vehicle can be shared!

With the advancement of technology, there electronic-based steering adaptations. Some of these technologies include:

- Power-controlled levers and rods for accelerating/braking: similar to mechanical rods and levers, but with a motor built in to make the movement easier

- Reduced effort steering: modifications made to the vehicle to reduce the strength required to turn the steering wheel

- Using joysticks or other electronic wheels to drive the vehicle: a modification can be made to the vehicle so that it is controlled by a computer. The vehicle is then driven with a wheel or joystick that is connected to the computer.

Secondary Controls (windshield wipers, turn signals, etc)

Secondary controls on a button system.

Secondary controls are used to interact with other drivers on the road (such as signaling and using the horn), and to manage the vehicle (e.g., use the windshield wipers, changing the transmission gear, starting the vehicle, managing the heating/air conditioning etc). A lot of these functions can be adapted so that they are controlled with the push of a button. For example, buttons can be placed on the head rest so that they can be pressed with the head, or on the door so that it can be pressed with the elbow. Buttons can activate a single function, or can be used to trigger several functions. The multiple buttons can be programmed to the function of your desire, and can be connected to the steering wheel or other location that is convenient to you. These adaptations come in a variety of set-ups, and will require customization to your needs.

Funding considerations

There are often costs associated with the various parts of getting back on the road. In general, fees are required for the initial driving assessment, rehabilitation both in a clinic setting and on the road, and for adaptive equipment. In Canada, there is often no funding for these costs; this is often paid out of pocket unless you have an injury claim or other funding source. As a result, funding can be a big barrier to returning to driving.

For more information on the related fees, contact your local driving rehabilitation center for.

Considerations when looking to buy a vehicle to adapt

When looking to buy a vehicle to adapt after your injury, some things to consider include:

Transfer abilities

What are your transfer abilities? Will you be staying in your wheelchair to drive or will you transfer to the driver seat? If you are able to transfer, how easy is it for your to transfer to a higher surface? Do you need a ramp to get in and out of the vehicle?

Wheelchair storage

If you are planning on transferring out of your wheelchair, where will you store it? In the front seat or back?

Adaptive equipment required

Does the equipment you need only fit in a certain type of vehicle, such as a van? Can the vehicle accommodate the hand controls you need?

Passengers

If you plan on driving others, will there be enough space for passengers in the vehicle once it has been adapted?

Parking

Will the vehicle fit in the parking space you have?

Some driver rehabilitation centers will also complete a vehicle modification assessment. This assessment will help you select the equipment you need to get you and your wheelchair into the vehicle safely. There is usually a fee for a vehicle modification assessment.

Considerations when driving an adapted vehicle

Two studies interviewed people with disabilities who drove adapted vehicles. Some challenges that were identified by the drivers included:

Pain

Pain was experienced in the wrists when driving long distances, especially with a twist accelerator. Shoulder pain was also reported after driving for a long time. You may want to consider what position your arms are in, what movements are used, and if you can do this over a long period of time.

Trunk strength

Having a weak core resulted in some drivers needing to slow down or brace themselves when driving at high speeds or on winding roads. People with a higher spinal cord injury level often need extra trunk support, as they are unable to use their arms for support when hand controls are being used.

Fatigue

Driving can be tiring in comparison to driving able-bodied, as more focus is required for driving an adapted vehicle.

Accessibility of the environment

Some drivers found that the location they drove to was inaccessible, and they were unable to et out of their vehicle. For example, some garages had a step to get out of them, had a steep hill to the entrance, or if there is not enough space to open a ramp.

After an SCI, many people continue to drive with the use of adaptive driving equipment. There are many modifications that can be made to a vehicle to suit your needs and enable you to drive again. However, prior to hitting the road, you will need to be evaluated by a driving rehabilitation specialist or occupational therapist. This evaluation will help the clinician understand your needs and limitations, and help them determine the best adaptations for you. Although getting back to driving may be a lengthy process, it can be beneficial for your sense of independence, and partaking in activities that you want to do again.

For a review of how we assess evidence at SCIRE Community and advice on making decisions, please see SCIRE Community Evidence.

Evidence for “Why is driving after SCI important?” is based on:

Mtetwa, L., Classen, S., & van Niekerk, L. (2016). The lived experience of drivers with a spinal cord injury: A qualitative inquiry. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 46(3), 55–62.

Norweg, A., Jette, A. M., Houlihan, B., Ni, P., & Boninger, M. L. (2011). Patterns, predictors, and associated benefits of driving a modified vehicle after spinal cord injury: Findings from the national spinal cord injury model systems. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 92(3), 477–483.

Evidence for “How do I know if I can drive?” is based on:

Anschutz, J. (2015). Driving After Spinal Cord Injury. Spinal Cord Injury Model System, (October). Retrieved from https://msktc.org/lib/docs/Factsheets/SCI_Driving.pdf

Kiyono, Y., Hashizume, C., Matsui, N., Ohtsuka, K., & Takaoka, K. (2001). Vehicle-driving abilities of people with tetraplegia. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 82(10), 1389–1392.

Norweg, A., Jette, A. M., Houlihan, B., Ni, P., & Boninger, M. L. (2011). Patterns, predictors, and associated benefits of driving a modified vehicle after spinal cord injury: Findings from the national spinal cord injury model systems. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 92(3), 477–483.

Peters, B. (2001). Driving performance and workload assessment of drivers with tetraplegia: An adaptation evaluation framework. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 38(2), 215–224.

Evidence for “What is a driving assessment based on?” is based on:

Anschutz, J. (2015). Driving After Spinal Cord Injury. Spinal Cord Injury Model System, (October). Retrieved from https://msktc.org/lib/docs/Factsheets/SCI_Driving.pdf

van Roosmalen, L., Paquin, G. J., & Steinfeld, A. M. (2010). Quality of Life Technology: The State of Personal Transportation. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, 21(1), 111–125.

Evidence for “What kind of vehicle can I drive?” is based on:

Haubert, L. L., Mulroy, S. J., Hatchett, P. E., Eberly, V. J., Maneekobkunwong, S., Gronley, J. K., & Requejo, P. S. (2015). Vehicle transfer and wheelchair loading techniques in independent drivers with paraplegia. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 3(139), 1-7.

van Roosmalen, L., Paquin, G. J., & Steinfeld, A. M. (2010). Quality of Life Technology: The State of Personal Transportation. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, 21(1), 111–125.

Evidence for “What adaptations are available for my vehicle?” is based on:

Haubert, L. L., Mulroy, S. J., Hatchett, P. E., Eberly, V. J., Maneekobkunwong, S., Gronley, J. K., & Requejo, P. S. (2015). Vehicle transfer and wheelchair loading techniques in independent drivers with paraplegia. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 3(139), 1-7.

van Roosmalen, L., Paquin, G. J., & Steinfeld, A. M. (2010). Quality of Life Technology: The State of Personal Transportation. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, 21(1), 111–125.

Evidence for ” What are some considerations when using and buying an adapted vehicle?” is based on:

Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation (2021). Vehicles and Driving. https://www.christopherreeve.org/living-with-paralysis/home-travel/driving

Hutchinson, C., Berndt, A., Gilbert-Hunt, S., George, S., & Ratcliffe, J. (2020). Modified motor vehicles: the experiences of drivers with disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(21), 3043–3051. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1583778

Mtetwa, L., Classen, S., & van Niekerk, L. (2016). The lived experience of drivers with a spinal cord injury: A qualitative inquiry. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 46(3), 55–62.

Image credits

- Wheelchair holiday bea disabled summer ©LonelyTaws, Pixabay License

- Eye ©Veronika Krpciarova, CC BY 3.0

- Stretch ©Andrejs Kirma, CC BY 3.0

- Brain ©Amethyst Studio, CC BY 3.0

- Mood ©shuai tawf, CC BY 3.0

- Adapted wheel with spinner, ©SCIRE Community Team

- Honda Odyssey (2018-present) ©Kevauto, CC BY-SA 4.0

- Eighth-generation Civic sedan ©OSX, CC 0

- Ford F-150 crew cab – 05-28-2011 ©IFVEHICLE, CC 0

- Collision warning brake support ©Ford Motor Company, CC BY 2.0

- Adapted Van ©SCIRE Community Team

- Haubert, L. L., Mulroy, S. J., Hatchett, P. E., Eberly, V. J., Maneekobkunwong, S., Gronley, J. K., & Requejo, P. S. (2015). Vehicle transfer and wheelchair loading techniques in independent drivers with paraplegia. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 3(139), 1-7.

- A disabled man in a wheelchair getting out of a vehicle ©CDC/Amanda Mills, CC 0

- BraunAbility Turny Evo Handicap Swivel Vehicle Seat Transfer Seat ©BraunAbility, 2020

- BraunAbility B&D Transfer Seat ©BraunAbility, 2020

- Special, vehicle, wheelchair ©CDC/Amanda Mills, CC 0

- QRT-360 ©Q’Straint, 2021

- Sure-Grip Tri-pin Spinner Knob ©Indemedical, 2021

- Adapted driving levers and rods. ©SCIRE Community Team

- Bever 8-touch Keypad ©Bever Mobility Products Inc

- Money ©Mahabbah, CC BY 3.0

Decide where you will place your wheelchair: in the front passenger seat, or the back seats. Those with weaker shoulder muscles should consider loading their wheelchair into the front seats.

Decide where you will place your wheelchair: in the front passenger seat, or the back seats. Those with weaker shoulder muscles should consider loading their wheelchair into the front seats.

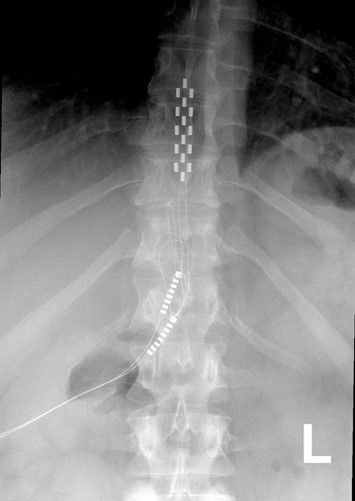

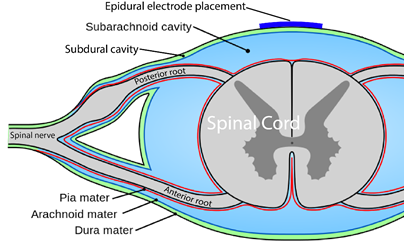

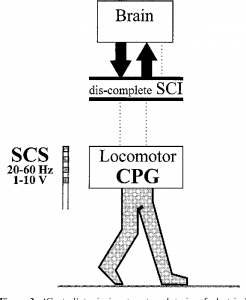

You are probably familiar with the term “epidural” already, as it is often mentioned in relation to childbirth. If a new mother says she had an epidural, what she usually means is that she had pain medication injected into the epidural space for the purpose of managing pain during birth.

You are probably familiar with the term “epidural” already, as it is often mentioned in relation to childbirth. If a new mother says she had an epidural, what she usually means is that she had pain medication injected into the epidural space for the purpose of managing pain during birth.

Neuromodulation methods to manage bladder function have usually involved stimulation of the sacral nerves (which are outside of the spinal cord), not with epidural spinal cord stimulation. This is reflected in the fact that almost no research exists regarding the effects of epidural stimulation on bowel and bladder function in the previous century.

Neuromodulation methods to manage bladder function have usually involved stimulation of the sacral nerves (which are outside of the spinal cord), not with epidural spinal cord stimulation. This is reflected in the fact that almost no research exists regarding the effects of epidural stimulation on bowel and bladder function in the previous century.

One of the consequences of SCI is the loss of muscle mass below the injury and a tendency to accumulate fat inside the abdomen (abdominal fat or visceral fat) and under the skin (subcutaneous fat). These changes and lower physical activity after SCI increase the risk for several diseases.

One of the consequences of SCI is the loss of muscle mass below the injury and a tendency to accumulate fat inside the abdomen (abdominal fat or visceral fat) and under the skin (subcutaneous fat). These changes and lower physical activity after SCI increase the risk for several diseases. The first use of epidural stimulation was as a treatment for chronic pain in the 1960s. Since then, it has been widely used for chronic pain management in persons without SCI. However, it is important to recognize that the chronic pain experienced by those without SCI is different from the chronic neuropathic pain experienced after SCI. This may explain, to some extent, why epidural stimulation has not been as successful in pain treatment for SCI. The mechanism by which electrical stimulation of the spinal cord can help with pain relief is unclear. Some research suggests that special nerve cells that block pain signals to the brain may be activated by epidural stimulation.

The first use of epidural stimulation was as a treatment for chronic pain in the 1960s. Since then, it has been widely used for chronic pain management in persons without SCI. However, it is important to recognize that the chronic pain experienced by those without SCI is different from the chronic neuropathic pain experienced after SCI. This may explain, to some extent, why epidural stimulation has not been as successful in pain treatment for SCI. The mechanism by which electrical stimulation of the spinal cord can help with pain relief is unclear. Some research suggests that special nerve cells that block pain signals to the brain may be activated by epidural stimulation. Using epidural stimulation to improve respiratory function is useful because it contracts the diaphragm and other muscles that help with breathing. Also, these muscles are stimulated in a way that imitates a natural pattern of breathing, reducing muscle fatigue. More common methods of improving respiratory function do not use epidural stimulation, but rather, directly stimulate the nerves that innervate the respiratory muscles. While such methods significantly improve quality of life and function in numerous ways, they are not without issues, including muscle fatigue from directly stimulating the nerves.

Using epidural stimulation to improve respiratory function is useful because it contracts the diaphragm and other muscles that help with breathing. Also, these muscles are stimulated in a way that imitates a natural pattern of breathing, reducing muscle fatigue. More common methods of improving respiratory function do not use epidural stimulation, but rather, directly stimulate the nerves that innervate the respiratory muscles. While such methods significantly improve quality of life and function in numerous ways, they are not without issues, including muscle fatigue from directly stimulating the nerves. In another study with two middle-aged females 5-10 years post-injury, one reported no change in sexual function and the other reported the ability to experience orgasms with epidural stimulation, which was not possible since her injury.

In another study with two middle-aged females 5-10 years post-injury, one reported no change in sexual function and the other reported the ability to experience orgasms with epidural stimulation, which was not possible since her injury. Botulinum toxin (Botox) injections and surgically implanted intrathecal Baclofen pumps are the most common ways to manage spasticity. Baclofen pumps are not without issues, however. Many individuals do not qualify for this treatment if they have seizures or blood pressure instability, and pumps require regular refilling.

Botulinum toxin (Botox) injections and surgically implanted intrathecal Baclofen pumps are the most common ways to manage spasticity. Baclofen pumps are not without issues, however. Many individuals do not qualify for this treatment if they have seizures or blood pressure instability, and pumps require regular refilling. In a study with a single participant (weak evidence) investigating walking, an individual implanted with an epidural stimulator also reported improvement in body temperature control, however details were not provided. More research is required to understand the role of epidural stimulation for temperature regulation.

In a study with a single participant (weak evidence) investigating walking, an individual implanted with an epidural stimulator also reported improvement in body temperature control, however details were not provided. More research is required to understand the role of epidural stimulation for temperature regulation.

In severe SCI, individuals may suffer from chronic low blood pressure and orthostatic hypotension (fall in blood pressure when moving to more upright postures). These conditions can have significant effects on health and quality of life. Some recent studies have looked at how epidural stimulation affects cardiovascular function to improve orthostatic hypotension. Overall, they show (weak evidence) that epidural stimulation immediately increases blood pressure in individuals with low blood pressure while not affecting those who have normal blood pressure. They also showed that there is a training effect with repeated stimulation. This means that after consistently using stimulation for a while, normal blood pressure can occur even without stimulation when moving from lying to sitting.

In severe SCI, individuals may suffer from chronic low blood pressure and orthostatic hypotension (fall in blood pressure when moving to more upright postures). These conditions can have significant effects on health and quality of life. Some recent studies have looked at how epidural stimulation affects cardiovascular function to improve orthostatic hypotension. Overall, they show (weak evidence) that epidural stimulation immediately increases blood pressure in individuals with low blood pressure while not affecting those who have normal blood pressure. They also showed that there is a training effect with repeated stimulation. This means that after consistently using stimulation for a while, normal blood pressure can occur even without stimulation when moving from lying to sitting. For individuals with tetraplegia, even some recovery of hand function can mean a big improvement in quality of life. Research into using epidural stimulation to improve hand function consists of one case study (weak evidence) involving two young adult males who sustained motor complete cervical spinal cord injury over 18 months prior.

For individuals with tetraplegia, even some recovery of hand function can mean a big improvement in quality of life. Research into using epidural stimulation to improve hand function consists of one case study (weak evidence) involving two young adult males who sustained motor complete cervical spinal cord injury over 18 months prior. Being able to control your trunk (or torso) is important for performing everyday activities such as picking things up or reaching for items. One study found that using epidural stimulation can increase the amount of distance you are able to lean forward. The improvement in forward reach occurred immediately when the stimulation was turned on. The two participants in this study were also able to reach more side to side as well, but the improvement was minor.

Being able to control your trunk (or torso) is important for performing everyday activities such as picking things up or reaching for items. One study found that using epidural stimulation can increase the amount of distance you are able to lean forward. The improvement in forward reach occurred immediately when the stimulation was turned on. The two participants in this study were also able to reach more side to side as well, but the improvement was minor.

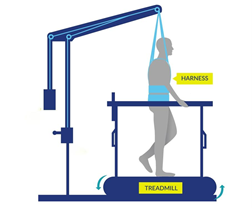

Some studies have also found that with extensive practice (e.g., 80 sessions), independent standing (i.e., standing without the help of another person, but holding onto a bar) may be achieved without epidural stimulation. Gaining the ability to stand may also occur with stand training combined with epidural stimulation. However, the findings with regard to the effect of stand training with epidural stimulation have been mixed. For example, one study showed that stand training for 5 days a week over a 4 month period with epidural stimulation resulted in independent standing for up to 10 minutes in an individual with a complete C7 injury, while another study has suggested that independent standing for 1.5 minutes can be achieved with epidural stimulation and 2 weeks of non-step specific training in an individual with complete T6 injury.

Some studies have also found that with extensive practice (e.g., 80 sessions), independent standing (i.e., standing without the help of another person, but holding onto a bar) may be achieved without epidural stimulation. Gaining the ability to stand may also occur with stand training combined with epidural stimulation. However, the findings with regard to the effect of stand training with epidural stimulation have been mixed. For example, one study showed that stand training for 5 days a week over a 4 month period with epidural stimulation resulted in independent standing for up to 10 minutes in an individual with a complete C7 injury, while another study has suggested that independent standing for 1.5 minutes can be achieved with epidural stimulation and 2 weeks of non-step specific training in an individual with complete T6 injury. Earlier research has found that epidural stimulation can help with the development of walking-like movements, but these movements do not resemble “normal” walking. Instead, they resemble slight up and down movements of the leg. Recent studies have shown that with 10 months of practicing activities while lying down on the back and on the side, in addition to standing and stepping training, people are able to take a step without assistance from another person or body weight support. While some individuals in these studies have been able to regain some walking function, they are walking at a very slow pace, ranging from 0.19 meters per second to 0.22 meters per second. This is much slower than the 0.66 meters per second required for community walking. For example, of the 4 participants in one study, two were able to walk on the ground with a walker, one was only able to walk on a treadmill, and one was able to walk on the ground while holding the hands of another person. These differences in walking abilities gained by participants were not expected.

Earlier research has found that epidural stimulation can help with the development of walking-like movements, but these movements do not resemble “normal” walking. Instead, they resemble slight up and down movements of the leg. Recent studies have shown that with 10 months of practicing activities while lying down on the back and on the side, in addition to standing and stepping training, people are able to take a step without assistance from another person or body weight support. While some individuals in these studies have been able to regain some walking function, they are walking at a very slow pace, ranging from 0.19 meters per second to 0.22 meters per second. This is much slower than the 0.66 meters per second required for community walking. For example, of the 4 participants in one study, two were able to walk on the ground with a walker, one was only able to walk on a treadmill, and one was able to walk on the ground while holding the hands of another person. These differences in walking abilities gained by participants were not expected.

In Canada, the cost for an institution to install an epidural stimulation system for back pain in those without spinal cord injury, which is a common procedure, was $21,595 CAD. The cost incurred by a Canadian citizen undergoing implantation in Canada is $0 as it is covered by publicly funded health care.

In Canada, the cost for an institution to install an epidural stimulation system for back pain in those without spinal cord injury, which is a common procedure, was $21,595 CAD. The cost incurred by a Canadian citizen undergoing implantation in Canada is $0 as it is covered by publicly funded health care.

As of 2019, many different models of exoskeletons exist, and this number continues to grow as research and technology progresses. However, it is important to note that only three have been approved by the FDA for sale in North America and only two have been approved for home use, while the other is only approved for research and rehabilitation purposes. The two that are approved for home use are the ReWalk and the Indego, while the Ekso has been approved for research and rehabilitation purposes. The current models of exoskeletons have the ability to move from 0.2-2.6 km/hr, and weigh between 12-38 kg.

As of 2019, many different models of exoskeletons exist, and this number continues to grow as research and technology progresses. However, it is important to note that only three have been approved by the FDA for sale in North America and only two have been approved for home use, while the other is only approved for research and rehabilitation purposes. The two that are approved for home use are the ReWalk and the Indego, while the Ekso has been approved for research and rehabilitation purposes. The current models of exoskeletons have the ability to move from 0.2-2.6 km/hr, and weigh between 12-38 kg.

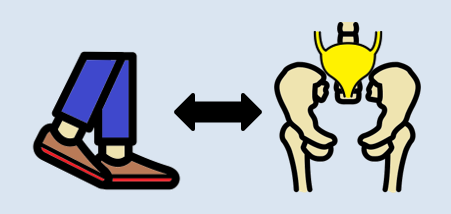

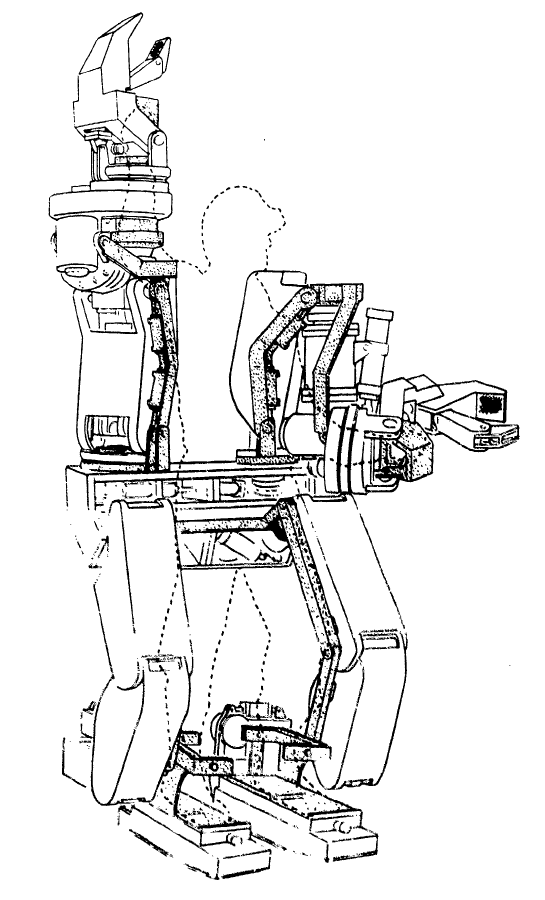

In 1972, a team from Yugoslavia developed the first functional exoskeleton: the kinematic walker. This device was the first of its kind; a powered robot consisting of a single hydraulic actuator (motor), which reduced its size. The kinematic walker was designed as a walking orthotic, and allowed for smooth movements to be made. Some movements the exoskeleton was able to perform included flexion and extension of the hip, knee, and ankle, in addition to abduction and adduction of the legs. Although this exoskeleton only weighed 12 kg, it required a separate power source and a computer, which were externally located from the exoskeleton.

In 1972, a team from Yugoslavia developed the first functional exoskeleton: the kinematic walker. This device was the first of its kind; a powered robot consisting of a single hydraulic actuator (motor), which reduced its size. The kinematic walker was designed as a walking orthotic, and allowed for smooth movements to be made. Some movements the exoskeleton was able to perform included flexion and extension of the hip, knee, and ankle, in addition to abduction and adduction of the legs. Although this exoskeleton only weighed 12 kg, it required a separate power source and a computer, which were externally located from the exoskeleton.

Some research (weak evidence) suggests that walking in an exoskeleton can provide good exercise for the heart and upper and lower limb strength in those with incomplete SCI. More details about the effect of exoskeletons on fitness are discussed below in the section:

Some research (weak evidence) suggests that walking in an exoskeleton can provide good exercise for the heart and upper and lower limb strength in those with incomplete SCI. More details about the effect of exoskeletons on fitness are discussed below in the section: oting a reduction in pain, but not enough to significantly impact everyday life (i.e., clinical significance). On the other hand, some weak evidence studies have found no effect of exoskeleton walking on pain.

oting a reduction in pain, but not enough to significantly impact everyday life (i.e., clinical significance). On the other hand, some weak evidence studies have found no effect of exoskeleton walking on pain.

Currently, there are only two exoskeleton models that have been approved for community use in North America. As such, there is limited evidence for using an exoskeleton in the community. In order to use an exoskeleton independently, individuals should be able to put on and take off the exoskeleton without professional help. Weak evidence has shown that individuals with paraplegia are able to independently put on and take off these devices, although those with tetraplegia are not. Additionally, weak evidence has shown that the time it takes to put on and take off an exoskeleton can be reduced with practice. Regarding walking speed in indoor versus outdoor environments, one weak evidence study has found that there are no significant differences in speed.

Currently, there are only two exoskeleton models that have been approved for community use in North America. As such, there is limited evidence for using an exoskeleton in the community. In order to use an exoskeleton independently, individuals should be able to put on and take off the exoskeleton without professional help. Weak evidence has shown that individuals with paraplegia are able to independently put on and take off these devices, although those with tetraplegia are not. Additionally, weak evidence has shown that the time it takes to put on and take off an exoskeleton can be reduced with practice. Regarding walking speed in indoor versus outdoor environments, one weak evidence study has found that there are no significant differences in speed.

There are some devices that facilitate pushing by amplifying your efforts (a mechanical advantage) using gears or levers. Using a device with a mechanical advantage will allow you to go further with a given push. One example of a device that provides mechanical advantage is a lever-propelled wheelchair. There are some lever devices that can be connected to your wheel (others require replacement of the rear wheels) that allow the user to propel by pushing the lever forward. Using a lever has two purported benefits: 1) using a longer lever to propel a wheelchair requires less force, and 2) using a lever enables a more favorable movement pattern of the hands, wrists, and shoulder. Together these may reduce the risk of injury. An example of this device is the NuDrive.

There are some devices that facilitate pushing by amplifying your efforts (a mechanical advantage) using gears or levers. Using a device with a mechanical advantage will allow you to go further with a given push. One example of a device that provides mechanical advantage is a lever-propelled wheelchair. There are some lever devices that can be connected to your wheel (others require replacement of the rear wheels) that allow the user to propel by pushing the lever forward. Using a lever has two purported benefits: 1) using a longer lever to propel a wheelchair requires less force, and 2) using a lever enables a more favorable movement pattern of the hands, wrists, and shoulder. Together these may reduce the risk of injury. An example of this device is the NuDrive. A PAPAW is a manual wheelchair with motorized rear wheels. The wheels are powered by a battery, which is attached to the back of the wheelchair. This type of wheelchair is controlled by normal pushing movements using the pushrims. PAPAWs assist individuals with limited strength or arm function by amplifying the force applied to the wheels. Each push on the pushrim by the user is sensed and proportionally amplified to increase the force to continue the forward movement. This also occurs for braking and turning (e.g., the wheels would detect a backwards force and apply a stronger braking force). This allows for users to go further with a given push, or to brake more efficiently with less force. When desired, the power assist function can be turned off. One limitation of using PAPAWs is the significantly increased weight of the wheelchair, which is especially noticeable when turned off. Another limitation is that the pushrims are damaged more easily, as this is where the sensors are located. Some examples of PAPAWs include the Alber E-motion and the Quickie Xtender.

A PAPAW is a manual wheelchair with motorized rear wheels. The wheels are powered by a battery, which is attached to the back of the wheelchair. This type of wheelchair is controlled by normal pushing movements using the pushrims. PAPAWs assist individuals with limited strength or arm function by amplifying the force applied to the wheels. Each push on the pushrim by the user is sensed and proportionally amplified to increase the force to continue the forward movement. This also occurs for braking and turning (e.g., the wheels would detect a backwards force and apply a stronger braking force). This allows for users to go further with a given push, or to brake more efficiently with less force. When desired, the power assist function can be turned off. One limitation of using PAPAWs is the significantly increased weight of the wheelchair, which is especially noticeable when turned off. Another limitation is that the pushrims are damaged more easily, as this is where the sensors are located. Some examples of PAPAWs include the Alber E-motion and the Quickie Xtender.

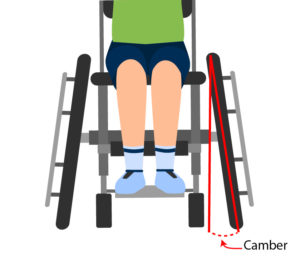

Rear mounted propulsion device generally connect to the bar underneath the wheelchair seat (i.e., the camber tube). These devices can power the wheelchair so that no manual propulsion is required, although turning and braking still require constant user control. Currently, there are two models commercially available that are light, compact, and easily attached: the SmartDrive and the Smoov. The SmartDrive is controlled with a wristband worn by the user. A double tap of the wristband (or similar accelerometer-sensed motion of the hand/arm when tapping the wheel or other surface) will activate the motor and begin accelerating the wheelchair. Another tap sets the speed, while the next double tap will stop the motor. Gripping on the handrim is usually still needed to slow down and stop the chair. Users are not required to propel the wheelchair once it is in motion; they are only required to steer. Good reaction time is required to operate the device; a learning curve is involved when first using the device. The Smoov operates via a frame mounted control knob to set the desired speed. Starting and stopping the motor is accomplished through tapping the knob. Turning, slowing, and stopping are similar to the SmartDrive operation.

Rear mounted propulsion device generally connect to the bar underneath the wheelchair seat (i.e., the camber tube). These devices can power the wheelchair so that no manual propulsion is required, although turning and braking still require constant user control. Currently, there are two models commercially available that are light, compact, and easily attached: the SmartDrive and the Smoov. The SmartDrive is controlled with a wristband worn by the user. A double tap of the wristband (or similar accelerometer-sensed motion of the hand/arm when tapping the wheel or other surface) will activate the motor and begin accelerating the wheelchair. Another tap sets the speed, while the next double tap will stop the motor. Gripping on the handrim is usually still needed to slow down and stop the chair. Users are not required to propel the wheelchair once it is in motion; they are only required to steer. Good reaction time is required to operate the device; a learning curve is involved when first using the device. The Smoov operates via a frame mounted control knob to set the desired speed. Starting and stopping the motor is accomplished through tapping the knob. Turning, slowing, and stopping are similar to the SmartDrive operation. Other rear-mounted systems, such as the Spinergy ZX-1, convert manual wheelchairs into a power wheelchair. The user backs up into the device, which connects to the wheelchair with a push of the button. This add-on lifts up the rear wheels of the wheelchair, converting it into a power wheelchair that is controlled with a joystick.

Other rear-mounted systems, such as the Spinergy ZX-1, convert manual wheelchairs into a power wheelchair. The user backs up into the device, which connects to the wheelchair with a push of the button. This add-on lifts up the rear wheels of the wheelchair, converting it into a power wheelchair that is controlled with a joystick.

The characteristics of your mobility device can also affect how you function in day-to-day life. For example, small tweaks to your wheelchair set-up can make it easier or more difficult to maneuver and propel yourself. The characteristics of your device may also affect the environments and situations that you can use it in, such as whether it can be used outside, during sports, or can be put in and out of a car independently.

The characteristics of your mobility device can also affect how you function in day-to-day life. For example, small tweaks to your wheelchair set-up can make it easier or more difficult to maneuver and propel yourself. The characteristics of your device may also affect the environments and situations that you can use it in, such as whether it can be used outside, during sports, or can be put in and out of a car independently. There are a variety of styles of wheelchairs and scooters, each with their own benefits and drawbacks. Properties of various mobility devices, such as the turning radius, the length and width, and the stability of the device may impact the types of activities that a wheelchair user can participate in. For example, a wheelchair that has a wide turning radius may not be able to maneuver in smaller stores with narrow aisles. Additionally, some devices perform better in inclement weather than others. This may be a consideration for individuals living in areas where it is often rains or snows.

There are a variety of styles of wheelchairs and scooters, each with their own benefits and drawbacks. Properties of various mobility devices, such as the turning radius, the length and width, and the stability of the device may impact the types of activities that a wheelchair user can participate in. For example, a wheelchair that has a wide turning radius may not be able to maneuver in smaller stores with narrow aisles. Additionally, some devices perform better in inclement weather than others. This may be a consideration for individuals living in areas where it is often rains or snows.

Standing

Standing

Folding wheelchairs are designed to be folded vertically and take up minimal storage space. This allows for easy portability (such as fitting the wheelchair into a car). However, these wheelchairs also have many moving parts that may break down or loosen over time, and are heavier than rigid wheelchairs. Folding wheelchair often have flip up, swing away or swing in footrests so they may be used by individuals that do not use the wheelchair full time, can stand or take some steps, or by those who foot propel.

Folding wheelchairs are designed to be folded vertically and take up minimal storage space. This allows for easy portability (such as fitting the wheelchair into a car). However, these wheelchairs also have many moving parts that may break down or loosen over time, and are heavier than rigid wheelchairs. Folding wheelchair often have flip up, swing away or swing in footrests so they may be used by individuals that do not use the wheelchair full time, can stand or take some steps, or by those who foot propel.

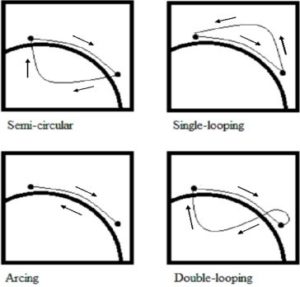

Propulsion pattern: the pattern you push your wheelchair with (e.g., where do your hands go when you push and after you’re done pushing) may also have an influence on your risk of injury. Some weak evidence suggests that using the semi-circular and double-loop-over may reduce the risk of nerve injury and are the most optimal ways to push your wheelchair. Further evidence (weak) has indicated that arcing may be more efficient for short bouts of high intensity pushing (like when going uphill).

Propulsion pattern: the pattern you push your wheelchair with (e.g., where do your hands go when you push and after you’re done pushing) may also have an influence on your risk of injury. Some weak evidence suggests that using the semi-circular and double-loop-over may reduce the risk of nerve injury and are the most optimal ways to push your wheelchair. Further evidence (weak) has indicated that arcing may be more efficient for short bouts of high intensity pushing (like when going uphill).

There are some situations in which FES may be unsafe to use. This not a complete list, speak to a health provider about your health history and whether FES is safe for you.

There are some situations in which FES may be unsafe to use. This not a complete list, speak to a health provider about your health history and whether FES is safe for you. Studies have shown that both FES arm exercise and FES cycling helps to maintain or improve strength after SCI. However, FES cycling may be more effective for maintaining strength after injury than improving strength that has already been lost. This is supported by moderate evidence from five studies.

Studies have shown that both FES arm exercise and FES cycling helps to maintain or improve strength after SCI. However, FES cycling may be more effective for maintaining strength after injury than improving strength that has already been lost. This is supported by moderate evidence from five studies. Fifteen studies have looked at FES for improving many different aspects of fitness after SCI. Taken altogether, these studies provide weak evidence that FES training done at least 3 days per week for 2 months helps to improve many aspects of cardiovascular fitness after SCI.

Fifteen studies have looked at FES for improving many different aspects of fitness after SCI. Taken altogether, these studies provide weak evidence that FES training done at least 3 days per week for 2 months helps to improve many aspects of cardiovascular fitness after SCI. Although it is commonly thought that increased muscle bulk from FES will reduce the risk of pressure sores, there are not very many studies which have looked at whether this actually happens. One study provides weak evidence that FES cycling for 2 years reduced the number of pressure ulcers that occurred after SCI. Another study showed that regular FES cycling showed a trend toward reducing seat pressures.

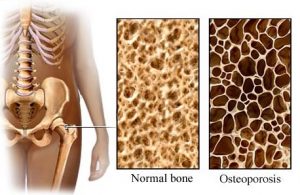

Although it is commonly thought that increased muscle bulk from FES will reduce the risk of pressure sores, there are not very many studies which have looked at whether this actually happens. One study provides weak evidence that FES cycling for 2 years reduced the number of pressure ulcers that occurred after SCI. Another study showed that regular FES cycling showed a trend toward reducing seat pressures. Research studies show that FES cycling does not prevent bone loss after SCI (moderate evidence from two studies). However, it may help to increase bone density that has already been lost, although the evidence for this is conflicting (based on six studies). It is not clear whether any gains in bone density last long-term or if continued FES treatment is needed for them to be maintained.

Research studies show that FES cycling does not prevent bone loss after SCI (moderate evidence from two studies). However, it may help to increase bone density that has already been lost, although the evidence for this is conflicting (based on six studies). It is not clear whether any gains in bone density last long-term or if continued FES treatment is needed for them to be maintained.