Authors: SCIRE Community Team | Reviewer: Bonnie Nybo | Published: 18 January 2018 | Updated: 16 October 2024

Key Points

- Most people with SCI experience some bladder changes after injury, but the type and symptoms depend on the characteristics of the injury.

- There are two main types of bladder problems after SCI:

- Spastic (reflex) bladder involves unpredictable emptying caused by overactive bladder muscles. It happens with injuries above T12.

- Flaccid (non-reflex) bladder involves an inability to empty the bladder because of “floppy” and underactive bladder muscles. It happens with injuries below T12.

- People with SCI are also at risk of complications like urinary tract infections, autonomic dysreflexia (if above T6), kidney and bladder stones, and kidney damage.

- Bladder care after SCI involves developing a regular bladder routine that meets your unique bladder needs. This may include a variety of treatments, such as catheters, medications and injections.

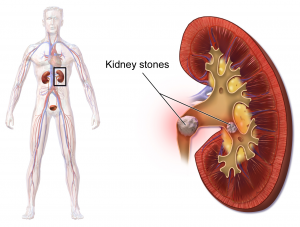

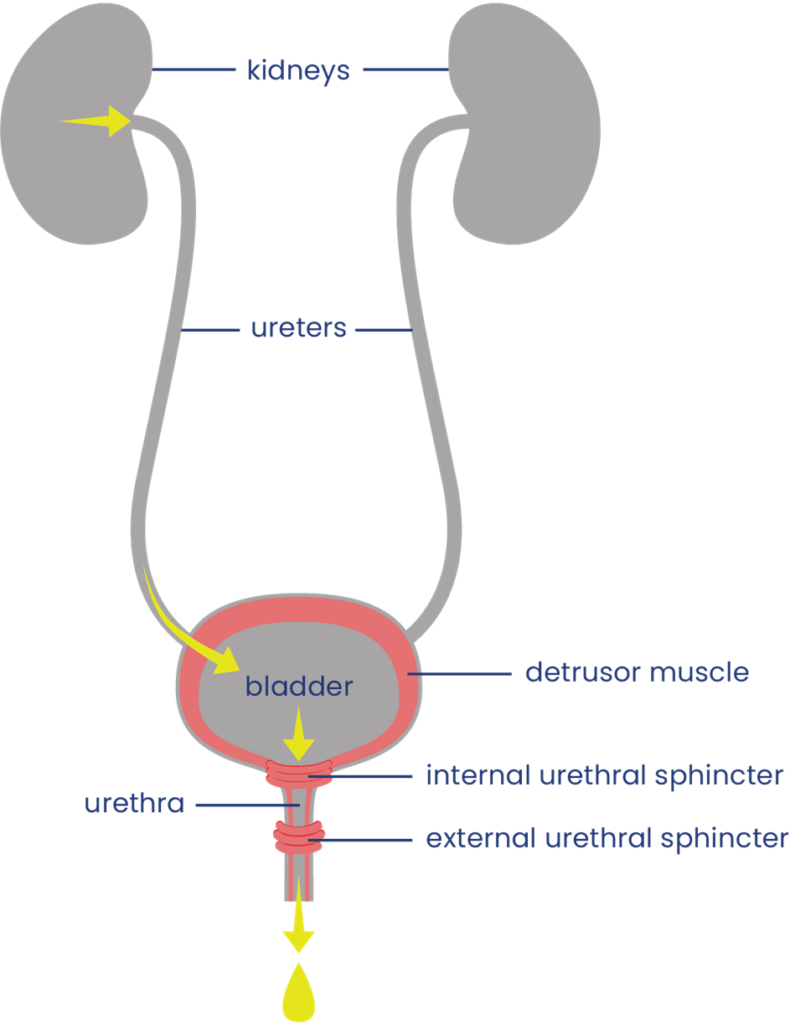

The urinary system

The urinary system helps the body filter and remove waste products and excess fluids. It consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, urethra, and bladder and sphincter muscles.

The urinary system helps the body filter and remove waste products and excess fluids. It consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, urethra, and bladder and sphincter muscles.

The kidneys filter the blood to produce urine, which is passed through narrow tubes called ureters to the bladder. The bladder is a sac that collects urine. Urine passes out of the body from the bladder through a tube called the urethra.

Filling and emptying of the bladder are partly controlled by the bladder muscles:

- The bladder wall muscle (detrusor muscle) is smooth muscle that covers the outside of the bladder. When it contracts, it squeezes the bladder and pushes urine out through the urethra. When it is relaxed, the bladder is loose and can be filled with urine.

- The bladder sphincter muscles (urethral sphincter or valve muscles) are two muscles which surround the exit of the bladder like a ring. When they tighten, they close off the urethra and hold urine in the bladder. When they relax, they allow urine to drain. The internal sphincter muscle is controlled unconsciously and the external sphincter muscle is controlled consciously.

Bladder function

When the bladder is not full, the bladder wall muscle is relaxed and urine produced by the kidneys passes through the ureters to fill the bladder. The bladder sphincter muscles are tightened so urine does not leak out.

When there is enough urine to stretch the bladder walls, a nerve signal is sent up the spinal cord to tell the brain that the bladder is full. Because the brain controls the external sphincter muscle, urine can be held until an appropriate time to empty.

When the bladder is to be emptied, signals are sent from the brain down the spinal cord to cause the coordinated squeezing of the bladder wall muscle and relaxation of the bladder sphincter muscles to allow urine to pass through the urethra and out of the body. Control of urination involves both bladder reflexes (in which emptying is triggered when the bladder is full) and voluntary control (in which urine can be held until a socially appropriate time to empty).

Neurogenic Bladder

Neurogenic bladder is bladder dysfunction caused by damage to the nerves, brain or spinal cord. After a spinal cord injury, nerve signals that normally allow the brain and bladder to communicate with one another cannot get through. This can affect bladder sensation and control.

Loss of bladder control

Signals from the brain are needed for the bladder muscles to contract and relax properly. If these signals cannot get through, the bladder muscles may contract too much, too little, or at the wrong times, depending on whether the person has spastic or flaccid bladder.

Reduced bladder sensation

Normally, signals that are sent up the spinal cord to the brain when the bladder is full. When the signals are interrupted, the ability to feel fullness and other sensations from the bladder may be reduced.

Bladder changes after SCI are different for everyone. Some people experience only mild changes to how the bladder works (such as greater sense of urgency when the bladder is full); while others experience complete loss of bladder sensation and control.

The symptoms of neurogenic bladder depend on the characteristics of the SCI, such as the level and completeness of the injury. There are two main types of neurogenic bladder after SCI, spastic bladder and flaccid bladder (see below).

Spastic Bladder

Spastic bladder (also called “reflex bladder” or “overactive bladder”) happens when the spinal cord is injured above T12. Spastic bladder happens because the brain can no longer control reflexes in the bladder muscles. This leads to tension in the bladder wall muscle when it is supposed to be relaxed and spasms of the bladder muscles which cause emptying.

Usually, the bladder sphincter muscles are also overactive and cannot coordinate very well with the bladder wall muscle. This is called detrusor dyssynergia or detrusor sphincter dyssynergia (DSD). When this happens, the bladder sphincter muscle tightens while the bladder wall muscle contracts, like squeezing a balloon that is tied off. This can cause high pressures within the bladder that can damage the bladder and kidneys.

Symptoms of spastic bladder:

- Loss of control of bladder emptying (incontinence), leading to random emptying (accidents), inability to empty when you want to and leaking

- Reflex emptying in response to things like touching the thigh or abdomen

- People with some bladder sensation may experience sudden strong urges or a frequent need to urinate

- Incomplete emptying of the bladder caused by poor coordination of the bladder wall muscle and bladder sphincter muscles (detrusor dyssynergia)

- Reduced or complete loss of bladder sensation

Flaccid bladder

Flaccid bladder (also called “non-reflex bladder” or “underactive bladder”) happens when the spinal cord is injured below T12-L1 (i.e cauda equina injuries). Flaccid bladder happens because there is a loss of both input from the brain and reflexes from the spinal cord. This causes the bladder wall muscle to stay loose and floppy all the time. When this happens, the bladder wall muscle cannot squeeze the bladder to empty urine.

Usually, the external sphincter muscle is also overly relaxed, causing leaking during activities like transfers and coughing. However, the internal sphincter muscle is often in spasm and does not relax enough to allow urine to pass out of the body easily.

Symptoms of flaccid bladder:

- Inability to empty the bladder, including loss of reflex emptying

- Incomplete bladder emptying, leading to some urine remaining in the bladder after emptying (urinary retention)

- Damage to the walls of the bladder when they are overstretched

- Backflow of urine back to the kidneys (reflux), which can damage the kidneys

- Reduced or complete loss of bladder sensation

Bladder examination

Bladder changes are diagnosed primarily through a bladder examination. A bladder examination typically involves several components:

- Your health provider will ask you questions about your medical history, symptoms, bladder routine, and current treatments.

- You may be asked to complete a “urinary diary” and/or detailed questionnaires about your bladder care. This often involves recording how often you empty your bladder, how much urine is produced each time, and details about your fluid intake (what you drink, when and how much).

- A physical examination may involve an inspection of the abdominal, pelvic and genital areas, as well as neurological testing of your reflexes, muscle strength, and sensation.

Other testing

Other testing may also be done if your health providers need further information.

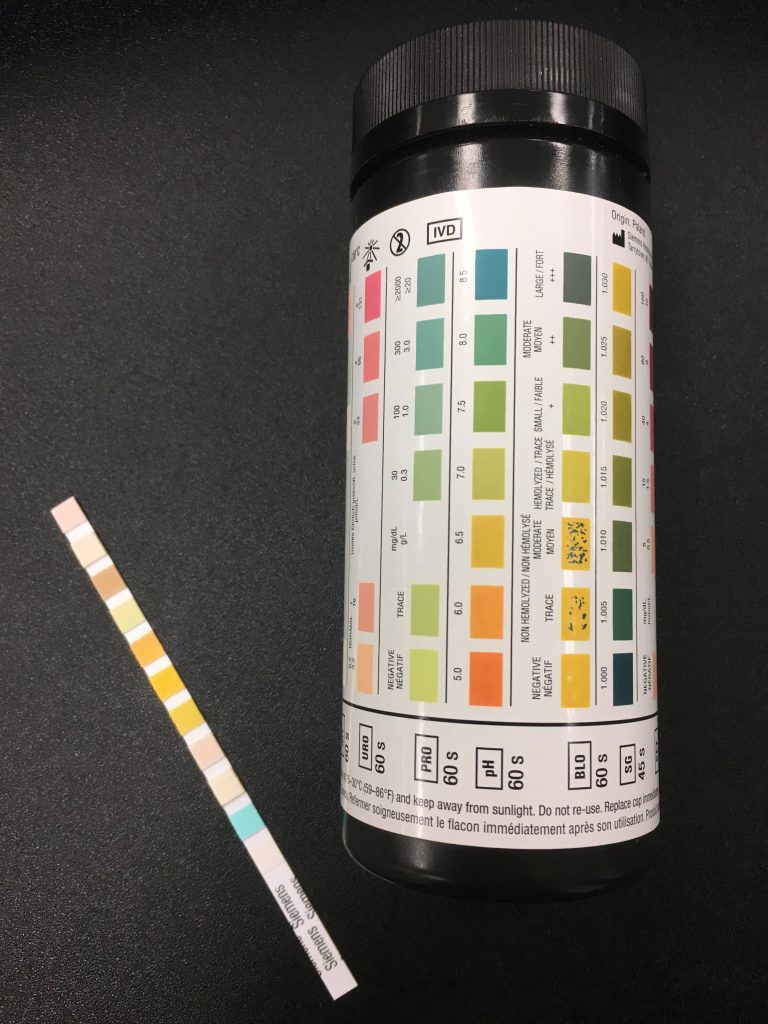

The dipstick or urine test strip is a basic diagnostic tool for identifying presence of substances or infection in urine.3

Urine culture

A urine culture and sensitivity test involves collecting urine in a sterile container to test for infection. Urine samples are usually collected mid-stream while emptying so the test is more accurate. If the sample is collected from an indwelling catheter, the catheter should be changed first. Samples are never taken from a urine drainage bag.

Blood tests

Blood tests may be done if there is concern about kidney function, kidney damage, or an infection. This usually involves testing for blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is an imaging technique that uses sound waves to visualize deep tissues. Ultrasound imaging may be done over the kidneys (known as renal ultrasound) to detect damage, kidney stones and infections.

Urodynamic testing

Urodynamic testing includes special tests that can be used to look at bladder pressures and urine flow. It can test how the bladder acts when it fills and empties, how well it coordinates, and the pressure within the bladder. This test may involve urinating into a special container that can measure the flow and volume of urine, insertion of a catheter to measure the leftover urine, and inserting water into the bladder to measure your ability to prevent emptying. It may also involve placing a small catheter into the rectum that measures the electrical activity of muscles.

Typical urodynamic measures

Bladder Capacity: The amount of urine the bladder can hold.

Voiding Efficiency: The amount of urine voided compared to the amount in the bladder before voiding. More efficiency means less urine is left in the bladder.

Bladder Compliance: The ability of the bladder to stretch in response to an increased amount of urine in the bladder. Without enough stretch there will be large increases in pressure, which is damaging to the urinary tract.

Imaging

Other imaging, such as x-ray, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are sometimes used for further investigation of bladder problems.

Cystoscopy

Cystoscopy (sometimes known as a “bladder scope”) is the use of a very small camera that can be inserted into the urethra to look at the urinary tract. Cystoscopy can be used to identify bladder stones, bladder health issues or damage including bladder cancer. It can also perform therapeutic procedures if needed such as removing tissue or stones.

Early bladder care

In the early hospital phase right after injury, the circulatory system is stabilizing, and the prevention of infections and other complications is the priority. During this phase, an indwelling catheter is placed in the bladder to constantly drain urine from the bladder. The catheter will be changed regularly and maintained in a sterile way by your nurse.

After the acute phase, bladder care will involve transitioning to more long-term bladder care techniques and developing a suitable bladder routine.

Bladder Routine

A bladder routine is a regular routine of bladder techniques and treatments that are done every day to maintain bladder function and health. This usually involves techniques to regularly empty the bladder, prevent leaks, and avoid serious complications long-term.

Every person’s routine is different and often involves trial and error to find the methods that best meet your unique symptoms, abilities, preferences, and lifestyle. There is a wide range of different techniques and treatments that may make up your routine, including catheters, medications, and methods of stimulation like electrical stimulation. Keep in mind that spastic bladder and flaccid bladder happen for different reasons and are managed differently.

Other things to consider when developing a bladder routine:

- Timing and amount of fluids

- Caffeine and alcohol consumption

- Scheduling of bladder emptying (such as how long between catheterizations, before going to bed or certain activities, after drinking fluids)

- What type of equipment to use, such as type of catheter and collection bag for different situations

- What to do if you have a bladder infection or other new health problem

- Regular assessment of bladder care with your health team

Spastic bladder management

The goals of spastic bladder management are to reduce overactivity in the bladder wall muscle which causes accidents, leaking, and wetness; as well as preventing high pressures within the bladder. This may include treatments such as:

- Indwelling catheters, condom catheters, and/or intermittent catheterization to drain the bladder

- Reflex voiding may help to empty the bladder for some people

- Anticholinergic medications may help to relax the bladder muscles

- Botulinum toxin (Botox) injections to help relax the bladder muscles

- Bladder augmentation surgery to increase the capacity of the bladder to hold urine

Flaccid bladder management

The goals of flaccid bladder management are to regularly empty the bladder to prevent overfilling and increased pressure in the bladder; and to prevent leaking and wetness. This may include treatments such as:

- Intermittent catheterization or indwelling catheters

- Condom catheters or pouches may be used to catch leaks but not for emptying

- Alpha-adrenergic blockers may help to relax the bladder sphincter muscles

- Botulinum toxin (Botox) injections

- Surgical techniques such as sphincterotomy or stents

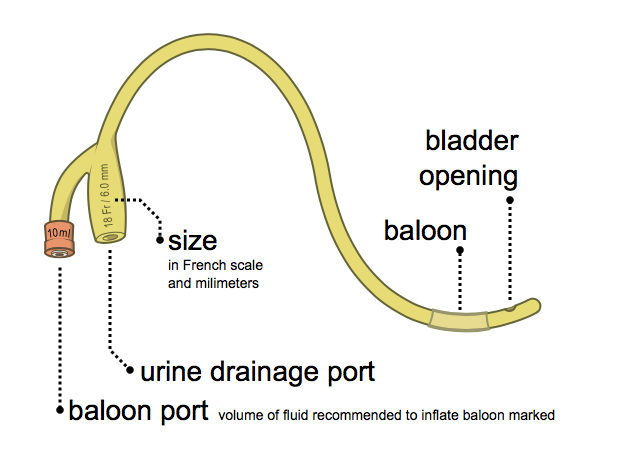

Urinary catheters are pieces of equipment that are used to drain urine from the bladder. There are many different ways that catheters are used.

Intermittent catheterization

Intermittent catheterization is when a catheter is inserted and removed through the urethra to drain the bladder at regular intervals throughout the day. Bladder emptying with intermittent catheterization must be done hygienically and on a regular schedule.

Intermittent catheterization is usually used by people who have enough hand function to perform the procedure independently. It is the closest method to normal bladder function, where the bladder fills continuously for a period of time and then empties all at once.

Indwelling catheters

Indwelling catheters (such as Foley catheters) are catheters that are inserted directly into the bladder and remain in place to continually drain the bladder. Indwelling catheters may be inserted through the urethra (urethral catheters) or through a surgically created hole through the abdomen (suprapubic catheters).

Indwelling catheters are usually used if inserting your own catheter independently is difficult or there are concerns about leaking between sessions of emptying.

Condom catheters (only for males)

Condom catheters are catheters that resemble a condom and are placed over the penis and connected through tubes to a collection device. Condom catheters are usually used by people that leak in between emptying or for individuals who have the ability to trigger emptying by causing a spasm of their bladder (reflex voiding).

One of the main concerns of condom catheters is incomplete bladder drainage, which can cause kidney damage. A careful medical examination is needed to ensure that condom catheters are a safe option for use.

Refer to our article on Urinary Catheters for more information!

Catching leaks

Some people may use medical “penis pouches” (loosely fitted bags that can be placed around the penis), pads, or other devices to catch small leaks in between catheterizations. These will depend on the person and their risk of other problems like pressure injuries, and should be discussed in detail with your health providers before use.

Reflex voiding is a technique that can be used by some people with spastic bladder to stimulate urination. Reflex voiding is usually done by tapping over the bladder lightly and repeatedly with the fingertips or the side of the hand to stimulate reflexes in the bladder muscles. This technique can be used to help improve bladder emptying during intermittent catheterization and when using condom catheters. However, only a small number of people can use this technique safely without increasing the pressure too high in the bladder. Speak to your health team for more information about this technique.

Many reflex voiding techniques are not recommended

Older techniques for reflex voiding such as the Valsalva maneuver (increasing abdominal pressure by holding the breath and bracing) and the Credé technique (applying manual pressure onto the bladder through the abdomen) are no longer recommended because they can cause too much pressure in the bladder, which can damage the kidneys.

Several medications may be used to help manage bladder problems after SCI. These may help to relax overactive muscles or cause the bladder muscles to contract, depending on the type of bladder change experienced. A number of other medications may also be used for different aspects of bladder treatment after SCI.

Inserting liquid medications into the bladder

Some medications may be dissolved in a liquid solution and introduced into the bladder through a catheter after emptying. The solution is then left in the bladder until the next urination. This is called an intravesical instillation. Intravesical instillations may be used because their effects are more specific to the bladder, instead of throughout the whole body as with oral medications.

Anticholinergic medications

Anticholinergic medications (sometimes called antimuscarinic medications) are used to relax muscle spasms in the bladder wall muscle. This can help to reduce pressure within the bladder, increase the ability of the bladder to hold urine, and help reduce incontinence.

Anticholinergic medications (sometimes called antimuscarinic medications) are used to relax muscle spasms in the bladder wall muscle. This can help to reduce pressure within the bladder, increase the ability of the bladder to hold urine, and help reduce incontinence.

There are many different types of anticholinergic medications, with the most common being:

- oxybutynin (Ditropan, Ditropal XL, Oxytrol, Uromax)

- tolterodine (Detrol)

- fesoterodine (Toviaz)

- trospium chloride (TCL, Trosec)

- propiverine hydrochloride (Mictonorm)

- darifenacin (Enablex)

- solifenacin (Vesicare)

These can be taken by mouth or administered directly into the bladder in a liquid form.

Alpha-adrenergic blockers

Alpha-adrenergic blockers are medications that are used to encourage the bladder sphincter muscles to relax to allow urine to flow out of the body. This can help with bladder emptying and help prevent urinary retention. Common alpha-adrenergic blockers that may be used include tamulosin, mosixylyte, terazosin, and phenoxybenzamine.

Botulinum toxin injections

Injecting small doses of some strains of botulinum toxin (Botox) into muscles can help to reduce muscle spasms. Injections into the bladder wall muscle or the external sphincter muscle can help to relax these muscles to help prevent leaking and incontinence or to improve bladder emptying. The effects of these injections can last for 6 to 12 months.

Injecting small doses of some strains of botulinum toxin (Botox) into muscles can help to reduce muscle spasms. Injections into the bladder wall muscle or the external sphincter muscle can help to relax these muscles to help prevent leaking and incontinence or to improve bladder emptying. The effects of these injections can last for 6 to 12 months.

Read our article on Botulinum Toxin for more information!

Other medications

Capsaicin, a chemical commonly found in hot peppers, and its derivative resiniferatoxin, may be administered as a liquid into the bladder to help reduce urinary frequency, leaking, and bladder pressures related to bladder wall muscle overactivity, and increase bladder capacity.

- Nociceptin/orphanin phenylalanine glutamine is another medication with effects similar to capsaicin and resiniferatoxin. It may also be given into the bladder to reduce overactivity in the bladder wall muscle.

- Medications that are normally used to treat spasticity may also help with bladder problems related to spastic bladder. For example, baclofen and clonidine may help with bladder function after SCI.

- Phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitors such as tadalafil and vardenafil may help to reduce overactivity in the bladder wall muscle and increase bladder capacity.

- 4-Aminopyridine (fampridine) improves the transfer of nerve signals, which may help individuals regain sensation and control of the bladder sphincter muscles to improve emptying.

Bladder surgery is usually only considered if other less-invasive treatments are not effective. Surgical procedures that may be used include the Mitrofanoff procedure, bladder augmentation, sphincterotomy (for males), and urethral stents.

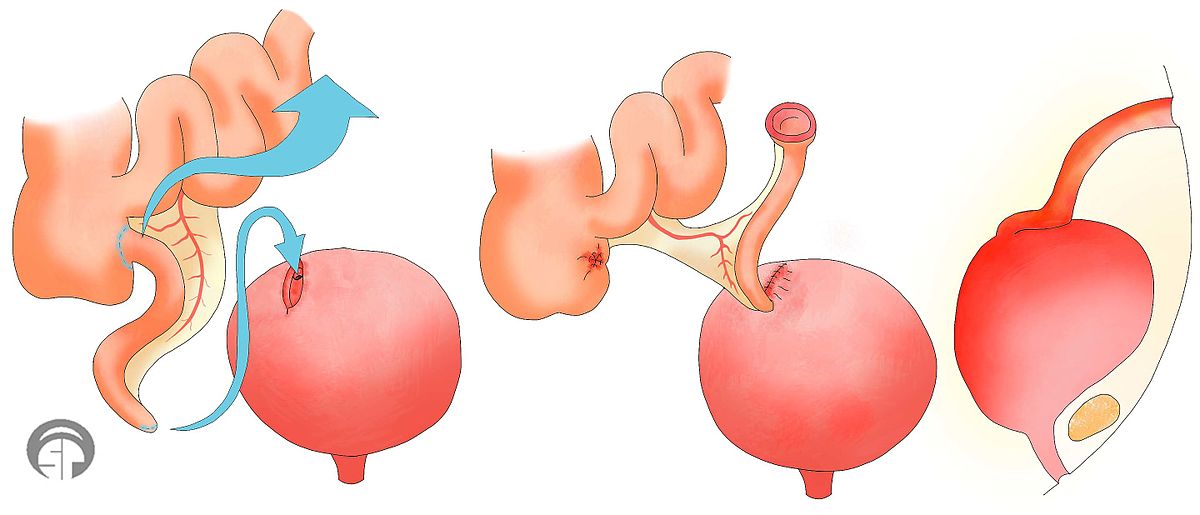

Mitrofanoff procedure

The Mitrofanoff procedure involves the use of the appendix or part of the intestine to create a channel between the abdomen and bladder. The channel self-seals shut when the catheter is removed. This channel can be used for insertion of a catheter for intermittent catheterization. The urine can then be drained into a cup or toilet. This may be useful for people who have difficulty self-catheterizing directly into the urethra and is often used for women (who have greater difficulty inserting catheters).

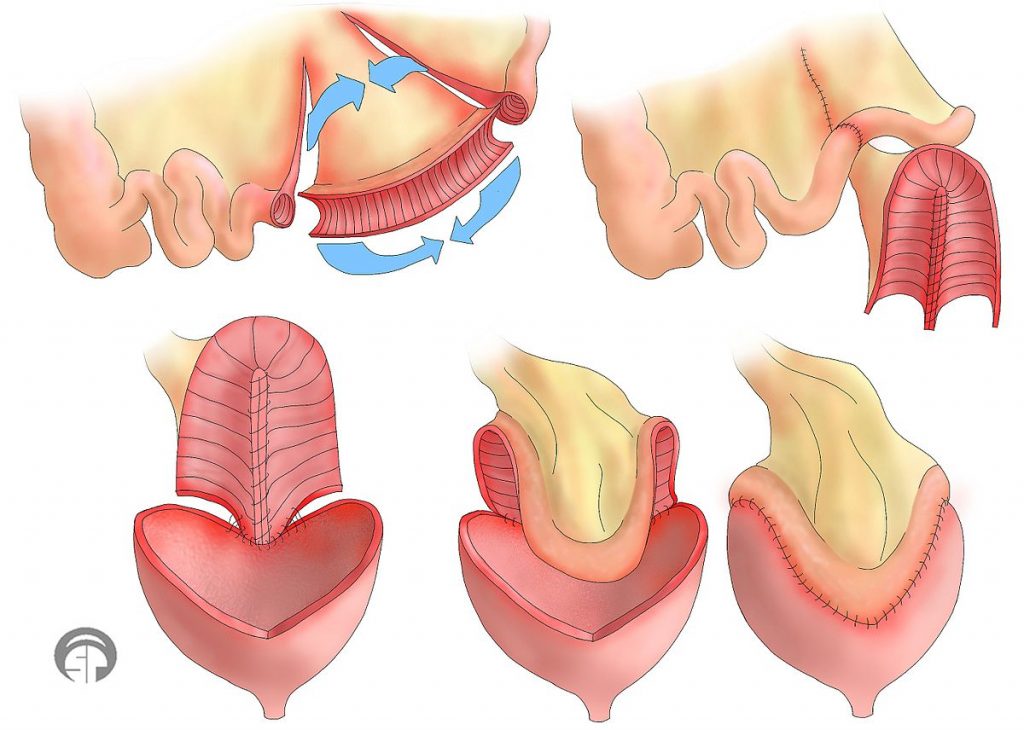

Bladder augmentation

Bladder augmentation (also called augmentation cystoplasty) is a procedure in which the bladder is made bigger to create more room to hold urine. This is done by removing a segment of the intestine and stitching this tissue to an incision into the bladder to make the bladder bigger. Bladder augmentation may help to reduce pressure in the bladder and help to prevent incontinence related to spastic bladder.

Bladder augmentation is a surgical procedure done to enlarge the bladder by using parts of the intestine.10

Sphincterotomy (for males)

Sphincterotomy is a surgical procedure where the internal sphincter muscle (the circular muscle that surrounds the outlet of the bladder) is cut to weaken the muscle. This is done to improve bladder emptying if this muscle is causing difficulties emptying. After a sphincterotomy, bladder emptying will happen; therefore, you must wear a collection device.

Urethral stents

Urethral stents are prosthetic tubes (usually coils of metal) with openings on both sides that are be inserted into the opening of the bladder to hold it open. This is done to allow for improved bladder emptying for people with difficulty emptying due to overactivity in the bladder sphincter muscles.

Electrical stimulation

Electrical stimulation can be used to help normalize the activity of the bladder muscles and control of bladder emptying. This may involve the implantation of a stimulator and electrodes that stimulate the sacral nerves that send brain signals to the bladder. This is sometimes referred to as neuromodulation.

Commercially available electrical bladder stimulation systems may be used for this purpose. However, these systems may be expensive and is not available in all locations.

Refer to our articles on Neuromodulation for more information!

Acupuncture

Acupuncture and electroacupuncture have also been suggested as treatment options to help with bladder function by influencing nerve signals related to bladder function.

Watch SCIRE’s video on bladder care to understand more about managing your bladder as you age.11

Typically, people will experience changes in urination as they age. Some may need to go to the bathroom more often because the bladder can’t store as much urine, or find that the flow of urine is weaker. Others may experience more urine leaking because the muscles that keep the bladder closed are weaker or the bladder contracts when it is not supposed to. The kidneys that filter your blood and produce urine may not function as well, and the risk of developing kidney stones increases.

Women, both during and post-menopause may experience an increase in the frequency of UTIs.

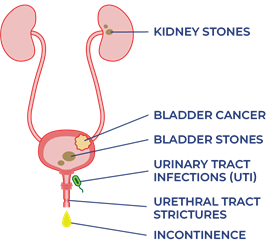

The aging bladder in SCI

For people aging with SCI, the long-term use of indwelling catheters to manage the bladder increases risk for bladder stones, bladder cancer, UTIs, and urinary tract deterioration. Long-term use of intermittent catheterization can increase risk for urethral strictures. People with neurogenic bladder can experience high pressures in the urinary tract and urine back up to the kidneys. Over time, this damages the structures of the urinary system and increases the risk for stones.

Bladder changes that people aging with SCI may experience:

- Increased UTIs

- Increased urine leaking (incontinence)

- Urethral strictures

- Bladder/kidney stones

- Increased risk of bladder cancer

- Damage to urinary tracts and kidneys

- Reduced kidney function

Bladder changes may also trigger spasticity and autonomic dysreflexia. Other aspects of aging like pain, osteoarthritis, decreased strength and mobility, and thinning of the skin, may also affect the ability to carry out bladder routines.

All of the changes from aging listed above could lead to a need to reassess bladder management strategies.

Refer to the “What other complications are related to bladder changes?” section for more information on specific bladder problems.

Managing bladder changes with age

If you experience changes to your bladder function as you age with SCI, consult regularly with a health care provider about your bladder management. Your family doctor, physiatrist, or urologist may be familiar with the check-ins necessary for bladder care as you age with a SCI.

Strategies to consider for the management of bladder changes may include:

- Changing the catheterization method to reduce UTIs, avoid urinary tract damage, or accommodate reduced hand and wrist function

- Screenings for bladder/kidney stones and urinary tract/kidney damage

- Regular screening for bladder cancer if indwelling catheter has been used for 5-10 years

- Consulting with professionals to determine the root cause of recurrent UTIs

- Antibiotic medication to treat UTIs (only use if experiencing symptoms to avoid developing antibiotic resistance)

- Supplements to prevent UTIs (i.e. D-mannose)

- Botulinum toxin (Botox) injections to relax bladder muscles

- Surgical procedures to make the bladder bigger, improve emptying, or make catheterization easier

- Additional caregiver help

- Quit or avoid smoking (smoking can up to quadruple risk for bladder cancer)

Many people with SCI change their bladder management as they age. In one study, half of participants changed their bladder management methods over 20 years. Over time, men who used condom drainage and women who used straining to manage their bladder were most likely to change their management methods. The use of indwelling catheters increased for men. A change to intermittent catheters or suprapubic indwelling catheters for bladder management increased for both men and women.

There is research looking at the potential for epidural and transcutaneous nerve stimulation to improve bladder function and management. This may be available depending on your location.

When do I need to review or change my bladder routine?

- Your current routine is not working anymore.

- The time and energy you spend on bladder management is limiting time spent with family/friends or doing things you love.

Questions to ask yourself to manage bladder changes

- What has changed (issues, challenges, barriers)?

- When did the change start?

- What is the root cause of the change? (medical illness, injury, surgery, mobility, weakness, cognitive changes, social changes, financial changes)

- What treatments or recommendations have been tried so far?

- What has worked and what has not?

- When was the most recent review of bladder with a family doctor or specialist such as a urologist or physiatrist?

Refer to the “Medications and injections”, “Bladder surgery and stents”, and “What other complications are related to bladder changes?” sections above for more information.)

Bladder changes are common after SCI. Bladder care is an important part of self-management after SCI to prevent complications and maintain good health and quality of life.

Bladder care after SCI involves developing a regular bladder routine that meets your unique bladder needs. This may include a variety of techniques and treatments, such as catheters, medications, injections and other treatments. Speak to your health team about which bladder management options are best for you. Regular follow up with your doctor is recommended yearly.

For a review of how we assess evidence at SCIRE Community and advice on making decisions, please see SCIRE Community Evidence.

This page has been adapted from the SCIRE Professional “Bladder Management” Module:

Hsieh J, McIntyre A, Iruthayarajah J, Loh E, Ethans K, Mehta S, Wolfe D, Teasell R. (2014). Bladder Management Following Spinal Cord Injury. In Eng JJ, Teasell RW, Miller WC, Wolfe DL, Townson AF, Hsieh JTC, Connolly SJ, Noonan VK, Loh E, McIntyre A, editors. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence. Version 5.0: p 1-196.

Available from: scireproject.com/evidence/bladder-management/

Biering-Sorensen F. Urinary tract infection in individuals with spinal cord lesion. Curr Opin Urol 2002;12(1):45-49.

Chancellor MB, Bennett C, Simoneau AR, Finocchiaro MV, Kline C, Bennett JK et al. Sphincteric stent versus external sphincterotomy in spinal cord injured men: Prospective randomized multicenter trial. J Urol 1999;161(6):1893-1898.

Chancellor MB, Karasick S, Strup S, Abdill CK, Hirsch IH, Staas WE. Transurethral balloon dilation of the external urinary sphincter: Effectiveness in spinal cord-injured men with detrusor-external urethral sphincter dyssynergia. Radiology 1993b;187(2):557-560.

Chancellor MB, Karusick S, Erhard MJ, Abdill CK, Liu JB, Goldberg BB, Staas WE. Placement of a wire mesh prosthesis in the external urinary sphincter of men with spinal cord injuries. Radiology 1993c;187(2):551-555.

Chartier-Kastler E, Amarenco G, Lindbo L, Soljanik I, Andersen HL, Bagi P, Gjodsbol K, Domurath B. A prospective, randomized, crossover, multicenter study comparing quality of life using compact versus standard catheter for intermittent self-catheterization. J Urol 2013;190:942-947.

Cheng P-T, Wong M-K, Chang P-L. A therapeutic trial of acupuncture in neurogenic bladder of spinal cord injured patients-A preliminary report. Spinal Cord 1998;36(7):476-480.

Creasey GH, Grill JH, Korsten M, HS U, Betz R, Anderson R et al. An implantable neuroprosthesis for restoring bladder and bowel control to patients with spinal cord injuries: A multicenter trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001;82(11):1512-1519.

Das A, Chancellor MB, Watanabe T, Sedor J, Rivas DA. Intravesical capsaicin in neurologic impaired patients with detrusor hyperreflexia. J Spinal Cord Med 1996;19(3):190-193.

DeSeze M, Wiart L, de Seze MP, Soyeur L, Dosque JP, Blajezewski S et al. Intravesical capsaicin versus resiniferatoxin for the treatment of detrusor hyperreflexia in spinal cord injured patients: A double-blind, randomized, controlled study. J Urol 2004;171(1):251-255.

DeSeze M, Wiart L, Joseph PA, Dosque JP, Mazaux JM, Barat M. Capsaicin and neurogenic detrusor hyperreflexia: A double-blind placebo-controlled study in 20 patients with spinal cord lesions. Neurourol Urodyn 1998;17(5):513-523.

DeVivo, M.J. Sir Ludwig Guttman Lecture: Trends in SCI rehabilitation outcomes from model systems in the United States:1973-2006. Spinal Cord 2007;45(11):713-721.

Evans RJ. Intravesical therapy for overactive bladder. Current Urology Reports 2005;6:429-433.

Farag FF, Martens FM, Rijkhoff NJ, Heesakkers JP. Dorsal genital nerve stimulation in patients with detrusor overactivity: A systematic review. Curr Urol Rep 2012;12(5):385-388.

Foxman B. Epidemiology of urinary tract infections: Incidence, morbidity, and economic costs. Dis Mon;49(2):53-70.

Gobeaux N, Yates DR, Denys P, Even‐Schneider A, Richard F, Chartier‐Kastler E. Supratrigonal cystectomy with hautmann pouch as treatment for neurogenic bladder in spinal cord injury patients: Long‐term functional results. Neurourology and urodynamics 2012;31(5):672-676.

Goldman HB, Amundsen CL, Mangel J, Grill J, Bennet M, Gustafson KJ, Grill WM. Dorsal genital nerve stimulation for the treatment of overactive bladder symptoms. Neurourol Urodyn 2008;27(6):499-503.

Greenstein A, Rucker KS, Katz PG. Voiding by increased abdominal pressure in male spinal cord injury patients–long term follow up. Paraplegia 1992;30(4):253-255.

Grijalva I, Garcia-Perez A, Diaz J, Aguilar S, Mino D, Santiago-Rodriguez E, et al. High doses of 4-aminopyridine improve functionality in chronic complete spinal cord injury patients with MRI evidence of cord continuity. Arch Med Res 2010;41:567-575.

Groah SL, Weitzenkamp DA, Lammertse DP, Whiteneck GG, Lezotte DC, Hamman RF. Excess risk of bladder cancer in spinal cord injury: evidence for an association between indwelling catheter use and bladder cancer. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002;83(3):346-351.

Groah SL, Weitzenkamp DA, Lammertse DP, Whiteneck GG, Lezotte DC, Hamman RF. Excess risk of bladder cancer in spinal cord injury: evidence for an association between indwelling catheter use and bladder cancer. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002;83(3):346-351.

Gurung PM, Attar KH, Abdul-Rahman A, Morris T, Hamid R, Shah PJ. Long-term outcomes of augmentation ileocystoplasty inpatients with spinal cord injury: A minimum of 10 years of follow-up. BJU Int 2012;109(8):1236-1242.

Hackler RH. Long-term Suprapubic cystostomy drainage in spinal cord injury patients. Br J Urol 1982;54(2):120-121.

Hakenberg OW, Ebermayer J, Manseck A, Wirth MP. Application of the Mitrofanoff principle for intermittent self-catheterization in quadriplegic patients. Urology 2001;58(1):38-42.

Hansen J, Media S, Nohr M, Biering-Sorensen F, Sinkjaer T, Rijkhoff NJ. Treatment of neurogenic detrusor overactivity in spinal cord injured patients by conditional electrical stimulation. J Urol 2005;173(6):2035-2039.

Hassouna M, Elmayergi N, Abdelhady M. Update on sacral neuromodulation: Indications and outcomes. Curr Urol Rep 2003 Oct;4(5):391-398.

Hikita K, Honda M, Kawamoto B, Panagiota T, Inoue S, Hinata N. Botulinum toxin type A injection for neurogenic detrusor overactivity: Clinical outcome in Japanese patients. International J Urol 2013;20(1):94-99.

Hohenfellner M, Humke J, Hampel C, Dahms S, Matzel K, Roth S, Thuroff JW, Schultz-Lampel D. Chronic sacral neuromodulation for treatment of neurogenic bladder dysfunction: Long-term results with unilateral implants. Urology 2001;58(6):887-892.

Horvath EE, Yoo PB, Amundsen CL, Webster GD, Grill WM. Conditional and continuous electrical stiulation increase cystometric capacity in persons with spinal cord injury. Neurourol Urodyn 2010;29(3): 401-407.

Juma S, Mostafavi M, Joseph A. Sphincterotomy: Long-term complications and warning signs. Neurourol Urodyn 1995;14(1):33-41

Katsumi HK, Kalisvaart JF, Ronningen LD, Hovey Rm. Urethral versus suprapubic catheter: Choosing the best bladder management for male spinal cord injury patients with indwelling catheters. Spinal Cord 2010;48(4):325-329.

Katz PG, Greenstein A, Severs SL, Zampieri TA, Singh SK. Effect of implanted epidural stimulator on lower urinary tract function in spinal-cord-injured patients. Eur Urol 1991;20(2):103-106.

Kaufman JM, Fam B, Jacobs SC, Gabilondo F, Yalla S, Kane JP et al. Bladder cancer and squamous metaplasia in spinal cord injury patients. J Urol 1977;118(6):967-971.

Kim JH, Rivas DA, Shenot PJ, Green B, Kennelly M, Erickson JR et al. Intravesical resiniferatoxin for refractory detrusor hyperreflexia: A multicenter, blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Spinal Cord Med 2003;26(4):358-363.

Kirkham AP, Knight SL, Craggs MD, Casey AT, Shah PJ. Neuromodulation through sacral nerve roots 2 to 4 with a Finetech-Brindley sacral posterior and anterior root stimulator. Spinal Cord 2002;40(6):272-281.

Kirkham APS, Shah NC, Knight SL, Shah PJR, Craggs MD. The acute effects of continuous and conditional neuromodulation on the bladder in spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2001;39(8):420-428.

Kutzenberger J, Domurath B, Sauerwein D. Spastic bladder and spinal cord injury: Seventeen years of experience with sacral deafferentation and implantation of an anterior root stimulator. Artif Organs 2005;29(3):239-241.

Lazzeri M, Calo G, Spinelli M, Guerrini R, Salvadori S, Beneforti P et al. Urodynamic effects of intravesical nociceptin/orphanin FQ in neurogenic detrusor overactivity: A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Urology 2003;61(5):946-950.

Lazzeri M, Spinelli M, Beneforti, P, Zanollo A, Turini D. Intravesical resiniferatoxin for the treatment of detrusor hyperreflexia refractory to capsaicin in patients with chronic spinal cord diseases. Scandinavian J Urol and nephrology 1998;32(5):331-334.

Locke JR, Hill DE, Walzer Y. Incidence of squamous cell carcinoma in patients with long-term catheter drainage. J Urol 1985;133(6):1034-1035.

Lombardi G, Del PG. Clinical outcome of sacral neuromodulation in incomplete spinal cord injured patients suffering from neurogenic lower urinary tract symptoms. Spinal Cord 2009;47:486-491.

Nicolle LE, Bradley S, Colgan R, Rice JC, Schaeffer A, Hooton TM. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2005;40(5):643-654.

Ord J, Lunn D, Reynard J. Bladder management and risk of bladder stone formation in spinal cord injured patients. Journal d’urologie 2003;170(5):1734-1737.

Pan D, Troy A, Rogerson J, Bolton D, Brown D, Lawrentschuk N. Long-term outcomes of external sphincterotomy in a spinal injured population. J Urol 2009;181:705-709.

Perkash I, Kabalin JN, Lennon S, Wolfe V. Use of penile prostheses to maintain external condom catheter drainage in spinal cord injury patients. Paraplegia 1992;30(5):327-332.

Perkash I. Efficacy and safety of terazosin to improve voiding in spinal cord injury patients. J Spinal Cord Med 1995;18(4):236-239.

Petersen T, Nielsen J, Schrøder H. Intravesical capsaicin in patients with detrusor hyper-reflexia: A placebo-controlled cross-over study. Scandinavian J Urol and nephrology 1999;33(2):104-110.

Popovic MR. Sacral root stimulation. Spinal Cord. 2002 Sep;40(9):431.

Sanford MT, Suskind AM. Neuromodulation in neurogenic bladder. Transl Androl Urol. 2016 Feb;5(1):117-26.

Sheriff MK, Foley S, McFarlane J, Nauth-Misir R, Craggs M, Shah PJ. Long-term suprapubic catheterisation: Clinical outcome and satisfaction survey. Spinal Cord 1998;36(3):171-176.

Sievert KD, Amend B, Gakis G, Toomey P, Badke A, Kaps HP, Stenzl A. Early sacral neuromodulation prevents urinary incontinence after complete spinal cord injury. Ann Neurol 2010;67:74-84.

Woodbury MG, Hayes KC, Askes HK. Intermittent catheterization practices following spinal cord injury: A national survey. Can J Urol 2008;15(3):4065-4071.

Wyndaele JJ, Madersbacher H, Kovindha A. Conservative treatment of the neuropathic bladder in spinal cord injured patients. Spinal Cord 2001;39(6):294-300.

Wyndaele JJ. Conservative treatment of patients with neurogenic bladder. European Urology Supplements 2008;7(8):557-565.

Evidence for “How does aging affect the bladder with SCI?” is based on:

Charlifue S, Jha A, Lammertse D. Aging with Spinal Cord Injury. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2010;21(2):383-402. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2009.12.002

Raz R. Hormone Replacement Therapy or Prophylaxis in Postmenopausal Women with Recurrent Urinary Tract Infection. J Infect Dis. 2001;183(s1):S74-S76. doi:10.1086/318842

West DA, Cummings JM, Longo WE, Virgo KS, Johnson FE, Parra RO. Role of chronic catheterization in the development of bladder cancer in patients with spinal cord injury. Urology. 1999;53(2):292-297. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(98)00517-2

Zhang Z, Liao L. Risk factors predicting upper urinary tract deterioration in patients with spinal cord injury: a prospective study. Spinal Cord. 2014;52(6):468-471. doi:10.1038/sc.2014.63

Pavlicek D, Krebs J, Capossela S, et al. Immunosenescence in persons with spinal cord injury in relation to urinary tract infections -a cross-sectional study-. Immunity & Ageing. 2017;14(1):22. doi:10.1186/s12979-017-0103-6

Image Credits:

- The Urinary System ©SCIRE, CC BY-NC 4.0

- Modified from: Nephron Anatomy ©BruceBlaus, CC BY-SA 4.0

- Dipstick ©SCIRE, CC BY-NC 4.0

- Foley catheter EN ©Ikej Renesz, CC BY-SA 3.0

- Cewnik zewnetrzny 0211 ©Sobol2222 assumed (based on copyright claims), CC0 1.0

- Medications ©Steve Buissinne, CC0 1.0

- Syringe ©Arek Socha, CC0 1.0

- Chili ©PublicDomainPictures, CC0 1.0

- Mitrofanoff ©Aphelpsmd, CC BY-SA 4.0

- Ileocystoplasty JPEG ©Aphelpsmd, CC BY-SA 4.0

- Aging Bladder Thumbnail ©SCIRE, CC BY-NC 4.0

- Urinary System Aging Changes ©SCIRE, CC BY-NC 4.0