Author: Sharon Jang | Reviewer: Rachel Abel | Published: 25 May 2022 | Updated: ~

Finding adequate housing after a spinal cord injury (SCI) can be difficult, but is important for quality of life. This article addresses housing concerns and adaptations after SCI.

Key Points

- Having housing that is optimal for your needs can improve reintegration back into the community.

- Many factors play a role in where you are discharged to after being in the hospital. These factors include how well you can do basic self-care tasks, age, degree of impairment, and whether you have insurance.

- To make a house accessible, you can find/build a house that has been built for accessibility, or make your own adaptations for the home.

- There are a variety of adaptations and modifications that can be made in all rooms of the home to make it more accessible.

After a spinal cord injury (SCI), there is often an increased need for social support and accessibility in the environment. Due to these factors, careful planning and consideration are required for optimal housing. Housing is an important factor in transitioning back into the community, which is a strong predictor of quality of life. Some (weak) evidence has noted that housing can influence quality of life as it:

After a spinal cord injury (SCI), there is often an increased need for social support and accessibility in the environment. Due to these factors, careful planning and consideration are required for optimal housing. Housing is an important factor in transitioning back into the community, which is a strong predictor of quality of life. Some (weak) evidence has noted that housing can influence quality of life as it:

- Creates opportunities for community participation through its physical location (e.g., being close to community centers, libraries, shops, etc.).

- Creates a sense of safety.

- Promotes independence, if the house is accessible.

- Allows for socialization with family and friends.

If there is a mismatch between housing needs and the home a person is discharged to, weak evidence suggests that a variety of difficulties may arise, including:

- A loss of friendships.

- A lack of care or assistance.

- Negative experiences with other people, related to being in a wheelchair.

- A lack of control over daily activities.

- A lack of flexibility and restriction of participating in work and leisure.

Moving back into the community after SCI is both a test of the supportiveness of the environment, and the resilience and resourcefulness of the individual. These factors can determine the success of the transition back into the community. This article will specifically focus on optimizing housing after SCI.

After SCI, there are many factors that influence whether or not one can go home. These include:

- Not being psychologically ready.

- Inaccessible transportation or home.

- A lack of social support.

Where an individual will live after being discharged from a hospital or rehabilitation center is dependent on many factors, including:

How well you can perform basic self-care tasks independently

Self-care tasks include activities such as bathing, feeding, and dressing yourself. In research, this is often measured through a test called the Functional Independence Measure (FIM). Some weak evidence shows that lower levels of independence will increase the likelihood of moving into a nursing home, as one would require a higher level of care.

Degree of impairment

Those who are AIS D (i.e., those with movement and near-normal strength in at least half the muscles below the level of injury) have access to greater housing opportunities. This is related to the fact (weak evidence) that individuals with AIS D face less environmental barriers and require less housing adaptations.

Age

One weak evidence study has found that older individuals are 4% more likely to be discharged to an extensive care unit or nursing home.

Having pre-existing medical conditions

If one has pre-existing medical conditions prior to sustaining an SCI,weak evidence suggests that there is 10x greater chance of being discharged to a nursing home.

Insurance/private funding for equipment

One study indicated that being able to afford adaptive equipment may increase the chances of being discharged home. This is one of the most significant factors in returning home as funding is required for adaptive equipment, renovations, care, and other supplies. It is important that an individual is able to live independently in their homes.

When looking for a home after injury, one may choose to rent, buy, renovate, or build a home. If you decide to renovate or build a house, some ways you may design your home include creating a livable house or an adaptable house.

Livable housing

A house built with universal design includes no steps/stairs from the start. 7

Livable housing are houses that are developed to be fully accessible despite changing needs throughout one’s life. That is to say, they are built with accessibility in mind. This type of housing embraces the concept of universal design. Universal design is a concept in which buildings and products are created so that they are usable by all people without the need of adaptation or specialized design. Applied to a home, universal design could include designing a home without steps rather than having to add a ramp later, or having doorways wide enough to accommodate wheelchairs if needed. Universal design is most often implemented in the building phase, and is not implemented once the house is already built.

Adaptable housing

Adaptive housing are places of residence that have additional accessibility modifications for people with disabilities. This includes changes such as lowered cabinets, changing the kitchen to have leg room under the countertop, or changing the layout of the laundry room to make it more accessible.

Considerations prior to modifying your home

Talking with a peer prior to making modifications to your home can be greatly beneficial. 8

Modifying your home can be an exciting but costly process. Before you start making changes to your house, some things to consider include the following:

- What are you able and unable to do? Keep your abilities in mind and remind yourself of the key changes need to be done to help you to avoid over-designing your home.

- Who can you turn to for advice? While there are specialized companies that exist that can provide recommendations for your modifications, also be sure to chat with another peer with SCI for advice. They may have additional insight, or referrals to reputable specialized contractors. Additionally, occupational therapists are equipped with specialized knowledge to make a home more accessible.

- What equipment works best for you? Make sure you try out equipment to ensure that they will work for you before you buy!

There are many features that can be included or added to a home to make it more accessible. Below, we list some ways homes may be adapted. This list is not exhaustive. It is important that you discuss things with peers, and experts in home design/building to see what works best for you and your home. For more photos, please refer to SCI Saskatchewan’s Accessible Housing page.

In the kitchen above, note the stove dials on the front of the stove, the lowered sink, and the space to wheel under it.9

Kitchen

Kitchens can be inaccessible after SCI due to the inaccessibility of stoves, a lack of leg space under counters, and counters and sinks being too high. Some modifications that can be made in the kitchen include:

- Putting in lowered countertops.

- Ensuring there is space to wheel under the counter and stove.

- Using a wall-mounted oven so that it is at an appropriate height.

- Having drawers and cupboards with lever-style knobs (versus rounded knobs).

- Placing the stove next to the sink to facilitate easy transfer of a pot to a sink for draining.

- Having stoves with knobs at the front, which are easier to reach and use.

This bedroom has light switches at head height on both sides of the bed, and ample space around the bed for moving.10

Bedroom

Some modifications that can be made in the bedroom include:

- Ensuring there is enough space on both sides of the bed to wheel.

- Having a shorter bedframe or box spring to facilitate transfers from manual wheelchairs.

- Having hardwood or laminate flooring to maximize wheeling in the room, although a low pile carpet may be okay as well.

Placing a second, lower bar in the closet for easier reach.

An adapted roll in shower with grab bars and a handheld shower head (left), and a sink with space to wheel under (right).11-12

Bathroom

Bathrooms are often the number one barrier in a home, specifically the shower. Some things to consider include the toilet height, the sink height, and the shower/tub. Some newer buildings use toilets with higher seats as they are easier for older adults to stand up, but this can make transferring an issue. Some modifications that can be made in the bathroom include:

- Using non-slip tiles.

- Installing a grab-bar for toilet or shower transfers.

- Having adjustable angles on mirrors.

- Installing roll in showers, with sides of the shower on a slight angle towards the drain.

- Using a handheld shower head, with connection to a rail for adjustable height.

- Placing wheel-in sink – sinks with space under them for a wheelchair to fit.

- Adding a raised toilet seat or a taller toilet for easier transfer.

Living room

Living rooms can be busy spaces filled wit#q2nh furniture and electronics such as televisions. Some modifications that can be made to make the living room more accessible include:

- Using arm chairs with a straight back and arm may provide support for rising and sitting.

- Obtaining an electric reclining chair, which can help for repositioning and is easy to operate.

- Ensuring there is enough space between furniture to maneuver.

- Using hardwood flooring throughout the main common rooms.

- Having low windows so you can see out of them.

- Having an open concept living room/dining room for easy moving.

- Using gas fireplaces for easy lighting.

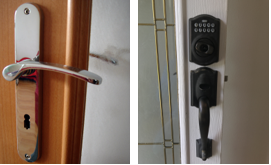

A lever-style door knob (left) and a lock key-pad (right) are some adaptations that can be used.13-14

Exterior

- Replace round doorknobs with lever door handles.

- Use a keyless entry/ use a code padlock in place of a traditional key.

- Use a folding ramp to go up a few stairs.

Other

- If building a ramp, ensure that the ramp is at least a 1:12 grade (i.e., for every one meter in elevation, the ramp should be 12 meters long).

- Create slip resistant surfaces with products such as non-slip strips, carpeting, or sand paint.

While renovations can make a home more accessible, it may not be in the budget for everyone. Instead, there are alternative lower cost strategies that can be used to improve accessibility in a home. These include the use of technology, addition of loops and straps, and modifications to existing home set-ups.

Smart devices. 15

Using technology for accessibility

With the advancement of technology, smart home features allow an individual to control various parts of the home through voice. With the use of devices such as the Google Home and Amazon Alexa, parts of the home such as lights, televisions, and the thermostat can be controlled with verbal commands. Alternatively, there are some models of powered wheelchairs that now come equipped with Bluetooth technology. This allows you to connect and control Bluetooth devices, such as lightbulbs, stereos, phones, and computers, with controls on a powered wheelchair.

A person opening a fridge door with their wrist. A loop has been added to the fridge door handle to facilitate this.16

Addition of loops and straps

A low-cost method of increasing accessibility of doors and drawers is through the addition of loops and straps. Loops and straps can be added to existing handles, such as on drawers, a fridge door, or on cabinets, to allow individuals to open these structures with their wrist or elbow. If possible, handles can also be swapped out for more accessible ones, such as bar-style handles.

Modifications to existing structures

While one can modify their home with extensive renovations, there are also minor things an individual can do to improve accessibility around the home. In the kitchen, consider removing cabinet doors lower down. This can allow for more leg room under sinks and countertops. Moreover, those with limited strength may want to consider rearranging the kitchen so that heavier objects (such as dishware), are lower down, or removing heavy objects altogether (e.g., by replacing ceramic dishware with plastic).

If doors are an issue in the home, typical door hinges may be replaced with Z-shaped or swing-away door hinges. These alternative hinges allow doors to open wider, which creates more space for a wheelchair to get through. As noted in the previous section, lever-style doorknobs can also be used to replace rounded doorknobs to facilitate the opening of doors.

Examples of adaptive equipment that can be used to control stove knobs.17-18

Adaptive equipment

In addition to renovations and modifications to the home, there are a variety of adaptive equipment that may make a home more accessible. For example, for those who are unable to reach or turn stove knobs, there are adaptive knob tuners available. Occupational therapists specialize in adapting spaces and equipment to meet each individual’s unique needs. For more information, refer to an occupational therapist.

Having housing that suits your unique needs after an SCI is important for community re-integration and your quality of life after injury. While there is the option of building a new house from scratch, it may be more feasible to adapt an existing home to increase accessibility and independence at home.

It is best to discuss all options with an occupational therapist or construction specialist to find out which modifications and equipment are suitable for you.

It is best to discuss all treatment options with your health providers to find out which treatments are suitable for you.

For a review of how we assess evidence at SCIRE Community and advice on making decisions, please see SCIRE Community Evidence.

Boucher N, Smith EM, Vachon J, Légaré I, Miller WC (2019). Housing and Attendant Services: Cornerstone of Community Reintegration after Spinal Cord Injury. In Eng JJ, Teasell RW, Miller WC, Wolfe DL, Townson AF, Hsieh JTC, Noonan VK, Loh E, McIntyre A, Querée M, Benton B, editors. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence. Version 6.0. Vancouver: p 1- 35.

Available from: SCIRE Professional Site

Evidence for “Why is housing important?” is based on:

Bergmark, B. A., Winograd, C. H., & Koopman, C. (2008). Residence and quality of life determinants for adults with tetraplegia of traumatic spinal cord injury etiology. Spinal Cord, 46(10), 684–689. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2008.15

Dickson, A., Ward, R., O’Brien, G., Allan, D., & O’Carroll, R. (2011). Difficulties adjusting to post-discharge life following a spinal cord injury: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Psychology, Health and Medicine, 16(4), 463–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2011.555769

Smith, B., & Caddick, N. (2015). The impact of living in a care home on the health and wellbeing of spinal cord injured people. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(4), 4185–4202. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120404185

Evidence for “What factors influence where I will live after the hospital?” is based on:

Azai, K., Young, J., McCallum, J., Miller, B., & Jongbloed, L. (2006). Factors influencing discharge location following high lesion spinal cord injury rehabilitation in British Columbia, Canada. Spinal Cord, 44(1), 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101778

Gulati, A., Yeo, C. J., Cooney, A. D., McLean, A. N., Fraser, M. H., & Allan, D. B. (2011). Functional outcome and discharge destination in elderly patients with spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord, 49(2), 215–218. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2010.82

Norin, L., Slaug, B., Haak, M., Jörgensen, S., Lexell, J., & Iwarsson, S. (2017). Housing accessibility and its associations with participation among older adults living with long-standing spinal cord injury. Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine, 40(2), 230–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790268.2016.1224541

Evidence for “How do I make my house accessible?” is based on:

Palmer, J., & Ward, S. (2013). The livable and adaptable house. Retrieved from: https://www.yourhome.gov.au/housing/livable-and-adaptable-house

Muir, K. (2020.) Adapting a home for wheelchair accessibility. Retrieved from: https://www.sralab.org/lifecenter/resources/adapting-home-wheelchair-accessibility

Evidence for “What does accessible housing look like?” is based on:

SCI Saskatchewan. Accessible housing. Retrieved from: https://scisask.ca/accessible-housing/

Muir, K. (2020.) Adapting a home for wheelchair accessibility. Retrieved from: https://www.sralab.org/lifecenter/resources/adapting-home-wheelchair-accessibility

Pettersson, C., Brandt, Å., Lexell, E. M., & Iwarsson, S. (2015). Autonomy and housing accessibility among powered mobility device users. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 69(5), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2015.015347

Image credits

- Woman in red and white long sleve shirt sitting on wheelchair ©Marcus Aurelius. Pexels License

- bathing ©ProSymbols, US. CC BY 3.0

- Modified from Outlines. ©Servier Medical Art. CC BY 3.0

- Birthday Candles. ©SCIRE Community Team

- Health. ©StringLabs, ID. CC BY 3.0

- ©SCIRE Community Team

- Architecture clouds daylight driveway. ©Pixabay. CC0

- Hamburg St Pauli Wheelchair Users. ©fsHH. Pixabay License.

- Wheelchair Accessible Kitchen ©SCIRE

- Inside our casita. ©Night Owl City. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

- After. ©Amanda Westmont. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

- Accessible Sink © Fairfax County CC BY-ND 2.0

- Door Handle. ©www.trek.today. CC BY 2.0

- Finished installation of a Schlage Key Pad Door lock system on a full light front door. ©Larry Spalding CC BY-SA 4.0

- Google home with home hub and home mini on table. ©Y2kcrazyjoker4 CC BY-SA 4.0

- Loop on fridge. ©Rachel Abel

- Stove knob reacher. ©Rachel Abel

- Adaptive stove knob turner. ©Rachel Abel