Author: SCIRE Community Team | Reviewer: Patricia Mills | Published: 12 April 2017 | Updated: 18 October 2017, 10 October 2024

This page provides information about pain and outlines common treatments for pain after spinal cord injury (SCI).

Key Points

- Pain is a common health concern after spinal cord injury.

- Pain can come from any part of the body, including the muscles, joints, organs, skin, and nerves.

- Nerve pain from an SCI is called neuropathic pain, and is a common cause of chronic pain after SCI.

- There are a wide range of treatments for pain, including mind-body treatments, physical treatments, medications, and surgeries.

- Managing pain after SCI can be challenging. You may need to try several strategies before you find what works best for you.

Pain is very common after SCI. Everyone experiences some form of pain after SCI and many people experience pain that is long-lasting and severe.

Pain can be very distressing and can get in the way of work, staying healthy, mood, and sleep. Because of this, pain is often considered to be the most challenging health problem to manage after SCI.

Pain after SCI can arise from any part of the body, but it is often nerve pain from the injury to the spinal cord itself that causes the most severe and troubling pain after SCI.

Listen to Matt’s experience with his gradual pain reduction after suffering from constant pain.

Muscle, joint, and bone pain

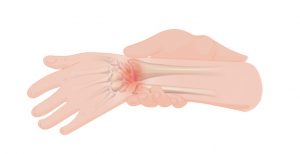

Pain from the muscles, joints, and bones is called musculoskeletal pain. This type of pain is felt in areas where there is normal sensation, such as above the level of SCI in an individual who has a complete injury, and also below the level of SCI in an individual with an incomplete injury and preservation of sensation below the level of injury. Musculoskeletal pain may feel ‘dull’, ‘achy’, or ‘sharp’ and usually happens during certain movements or positions. After SCI, musculoskeletal pain often comes from shoulder and wrist injuries, neck and back strain, or muscle spasms.

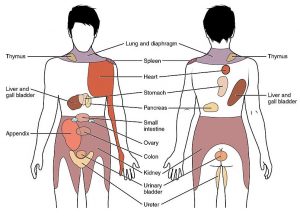

Internal organ pain

Pain from the internal organs (like the stomach, bladder, or heart) is called visceral pain (pronounced ‘VISS-err-el’). This type of pain can also be felt after SCI from areas with normal sensation. Visceral pain is usually felt in the abdomen, pelvis, or back but it is often hard to pinpoint exactly where it is coming from. This type of pain often feels ‘dull’, ‘tender’, or like ‘cramping’. Visceral pain is often caused by problems like constipation, bladder overfilling, or bladder infections.

Nerve pain (Neuropathic pain)

Pain from the nerves is called neuropathic pain. Neuropathic pain can be felt anywhere in the body, including below the level of SCI, even when there is no other feeling in the area. Neuropathic pain often has unique and unusual qualities compared to other types of pain:

- It may feel like it is ‘hot’, ‘burning’, ‘tingling’, ‘pricking’, ‘sharp’, ‘shooting’, ‘squeezing’, or like ‘painful cold’, ‘pins and needles’, or ‘an electric shock’

- It may happen spontaneously (‘out of the blue’)

- It may happen in response to things that do not normally cause pain (like the brush of clothing on the skin)

- It may be felt in areas far away from where the damaged nerve is (such as pain in the hand from a nerve injury in the neck)

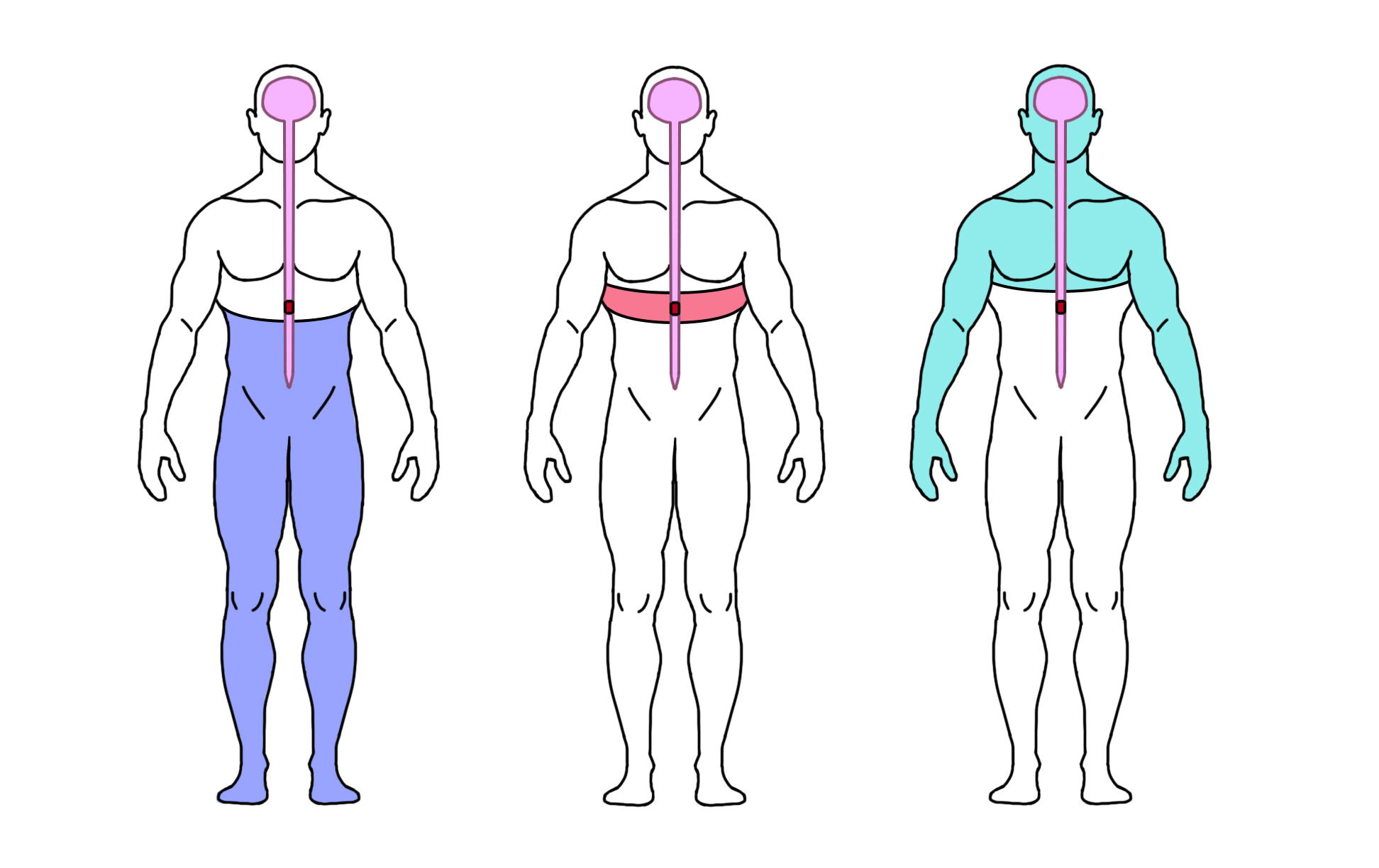

There are three main types of nerve pain after spinal cord injury:

At-level SCI pain is nerve pain felt at or near the level of SCI, usually as a band of pain around the torso or neck, or along the arms or legs.

Below-level SCI pain is nerve pain felt in any area below the SCI (including areas without other sensation).

Other neuropathic pain is nerve pain that is unrelated to the SCI and is felt above the level of the SCI. For example, an injury to nerves outside of the spine like nerve compression at the level of the wrist (i.e., carpal tunnel syndrome).

What is chronic pain?

Chronic pain, or persistent pain, is pain that is present for a long time (usually 6 months or more). Chronic pain is very different from pain experienced right after an injury (called acute pain). Long term or unrelieved pain can change how pain is experienced in the nervous system. This can lead to pain that is very complex and often challenging to treat. Chronic pain requires a very different approach to how it is understood and managed.

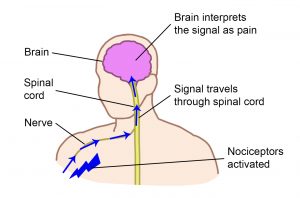

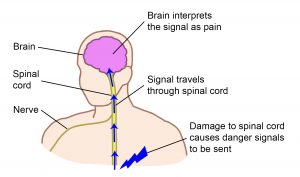

Pain happens differently depending on where it comes from in the body.

Pain from the body tissues

Nociceptors are special sensors in the body tissues (like the skin and muscles) that detect possible damage to the body.

When nociceptors are activated, they send signals through the nerves and spinal cord to the brain.

In the brain, these signals are recognized and interpreted together with other nerve signals from the brain and body, resulting in the experience of pain.

Pain from the nerves

Pain from the nerves is different. When the nerves themselves are injured, there are no nociceptors involved. Instead, the signals about potential damage come from somewhere along the pathway of nerves from the body to brain.

Damage to the nerves (including the spinal cord) can cause signals related to pain to be sent inappropriately, resulting in many of the unique features of neuropathic pain.

Pain can be turned up or down

The pain pathway is complex. Pain signals are not static but can be turned up or down (or modulated) by other nerve signals from both the body and brain. In other words, the pain experience can change depending on other factors, such as worsening during a urinary tract infection, or improving with distraction during enjoyable activities.

Nerve signals from the body, such as those involved in touch, can alter pain signals. This is like how rubbing the skin over a sore area of the body makes it feel better. Nerve signals from the brain, like those involved in emotions and thoughts, can also affect feelings of pain. For example, fear can make pain worse but feeling calm or even distracted can reduce pain.

This happens because of the many different nerve connections involved in the experience of pain.

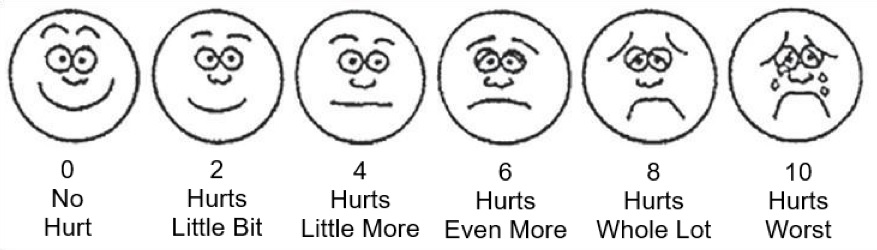

Since pain is a personal experience, the only way to measure pain is by asking you about your pain. One of the most common ways of measuring pain is using a simple scale from 0 to 10 (0 is “no pain” and 10 is “the worst pain”). There are also a number of questionnaires and other rating scales used to measure pain.

Other common questions about pain may include:

- Where is the pain located?

- What does the pain feel like? (Is it sharp, dull, or achy? or like tingling, pins and needles, or burning?)

- What makes the pain worse or better?

- How does the pain change throughout the day?

- How easily is pain provoked and how long does it last once started?

- How much does the pain interfere with your life?

These questions can help your healthcare team identify new pains, monitor changes over time, and determine if treatments are working.

There are many different treatment options for pain after SCI, ranging from conventional pain-relieving medications to a number of complementary and alternative medicine.

Treatments for pain after SCI may include:

- Addressing the cause of the pain (such as emptying the bladder or relieving constipation)

- Psychological and mind-body therapies

- Personal pain management strategies (such as relaxation and distraction)

- Physical treatments (such as physical therapy, massage, and heat)

- Electrical and magnetic treatments (such as TENS)

- Exercise

- Medications

- Surgery

- Other treatments

Finding the right treatment often involves trial and error to find what works best. It is important to discuss your treatment options with your health providers, including possible side effects and risks, other options, and your personal preferences.

Medications are often the first treatments for managing pain after SCI. Speak with your health providers for detailed information about any medication you are considering taking.

Medications for muscle, joint, and bone pain

Except for spasticity (muscle spasms below the level of SCI), most musculoskeletal pain after SCI is treated with common medications such as over-the-counter pain relievers. Because of this, the research evidence supporting the use of these medications is often based on research done in people without SCI and on expert opinion.

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen (Paracetamol) works to reduce pain and fever through mechanisms in the nervous system that are not well understood. Acetaminophen is usually taken by mouth and is a common first treatment for musculoskeletal pain after SCI.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen, and diclofenac reduce pain and inflammation by affecting chemicals in the inflammatory response. NSAIDs may be taken by mouth, or in some cases, applied to the skin over small areas. NSAIDs can sometimes worsen stomach problems, so they are used as a second-line treatment after SCI.

Corticosteroid injections

Corticosteroids mimic the effects of the hormone cortisol to reduce inflammation. Corticosteroids are injected into painful joints to relieve pain caused by inflammation, on an as-needed basis.

Antispasticity medications

Antispasticity medications such as Baclofen and Botulinum toxin (Botox) may be used to help relax painful muscle spasms caused by spasticity. Medications like Baclofen are usually taken by mouth. Medications can also be injected into the affected muscles (in the case of Botox) or into the spinal canal (in the case of Baclofen, via a pump that is surgically implanted).

Opioids

Opioid medications are a type of narcotic pain medication that binds to opioid receptors in the body, reducing pain messages sent to the brain. Opioids may be used for muscle, joint, and bone pain and sometimes for neuropathic pain after SCI. However, opioids can worsen constipation, induce sleep disordered breathing, and may be linked to dependence when used long-term. Therefore, although they are effective for managing pain in the short term, the goal is usually to get off opioids once the acute pain is controlled and avoid their use for chronic pain management.

See what Matt has to say about his initial thoughts about medications following an SCI.

Matt describes his experience with the withdrawal effects of stopping medication.

Medications for neuropathic pain

Neuropathic pain is treated with different types of medications than musculoskeletal pain. The strongest evidence supports using the anticonvulsants Gabapentin and Pregabalin and the antidepressants Amitriptyline, Nortriptyline, and Desipramine (all the same class of drug) for treating neuropathic pain after SCI. There are also many other medications that need further study for pain after SCI.

Anticonvulsants

Anticonvulsants, originally used for epileptic seizures, are thought to reduce neuropathic pain by calming hyperactive nerve cells in the spinal cord.

Antidepressants

Normally used to treat depression, certain types of antidepressants, for example, a class of drugs called tricyclic antidepressants such as Amitriptyline, are also used for neuropathic pain. Antidepressants increase the availability of the chemicals norepinephrine and serotonin in the body that may help to control pain signals in the spinal cord.

Anesthetic medications

Anesthetic medications like Lidocaine and Ketamine provide short-term pain relief by blocking the transmission of nerve signals involved in sensation and pain. These may be applied directly to the skin or given by injection, catheter, or intravenous line.

Clonidine

Clonidine is a drug that is normally used for lowering blood pressure. Clonidine may also stimulate parts of the spinal cord that decrease pain signals.

Capsaicin

Capsaicin is a chemical compound found in hot peppers that may reduce pain. Capsaicin reduces the action of a molecule called substance P that transmits pain signals in the body. Capsaicin is applied to the skin to reduce pain in small areas.

Cannabinoid medications

Cannabinoid medications like Nabilone contain chemicals called cannabinoids that are present in cannabis (marijuana). Cannabinoids also occur naturally in the body and play a role in reducing pain signals in the nervous system. Cannabinoid medications may be taken by mouth or inhaled.

Physical treatments like exercise, massage, and electrotherapy may be used as part of physical or occupational therapy sessions or at home. Research evidence suggests that regular exercise, shoulder exercise, acupuncture, and TENS may help reduce some types of pain after SCI. However, many of the other physical treatments have not been studied extensively among people with SCI and we do not know for sure how effective they are.

Regular exercise

Regular exercise, such as aerobic exercise, strength training, and exercise programs, can help a person stay healthy, reduce stress, and improve mood, which can help to treat pain.

Read our content on Movement and Exercise for more information!

Exercise for shoulder pain

Exercise is often used to treat pain from shoulder injuries. Shoulder exercise focuses on strengthening, stretching, and improving movement of the shoulder joint.

Read our article on Shoulder Injury and Pain for more information!

Massage

Massage is commonly used to help manage muscle pain.

Manual therapy

Hands-on techniques that involve mobilizing the soft tissues and joints to restore movement and reduce pain may be used for musculoskeletal pain. Manipulation techniques (‘thrust’ techniques) are not usually done after SCI because they can increase the risk of broken bones.

Heat

Heat is a common treatment for pain in the muscles and joints. Heat may reduce pain by stimulating sensory pathways that dampen pain signals. Heat should be used cautiously (or not used at all) in areas of reduced sensation or sensitive skin to avoid burns.

Acupuncture and dry needling

Acupuncture is an alternative practice derived from traditional Chinese medicine that involves the insertion of needles into specific points on the body. Acupuncture may help to stimulate the release of chemicals in the nervous system that reduce pain.

Dry needling (sometimes called intramuscular stimulation) is a technique for releasing muscle tension by stimulating sensitive points with an acupuncture needle.

Read our article on Acupuncture for more information!

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS)

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is the most common form of electrotherapy used in rehabilitation settings. TENS delivers electrical stimulation through electrodes placed on an area where pain is felt. The electrical stimulation may help to block pain signals in the spinal cord.

Read our article on TENS for more information!

Epidural stimulation

Epidural stimulation or spinal cord stimulation involves the surgical placement of electrodes on the spinal cord. While the mechanism is unclear, it is thought that the electric currents produced by the electrodes stimulate areas of the spinal cord to interrupt the pain signals being sent to the brain. Weak evidence suggests that only some individuals receive pain reduction, with the greatest reduction seen in individuals with an incomplete SCI.

A study reported that satisfaction for epidural stimulation in pain reduction significantly drops off over time, with only 18% of participants being satisfied after 3 years. The research for epidural stimulation in pain reduction is still limited, with relatively few studies specifically focused on individuals with SCI.

Read our article on Epidural Stimulation for more information!

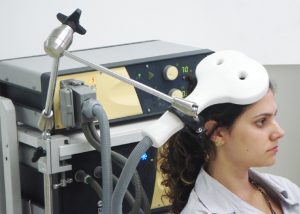

Future treatment options

Transcranial electrical stimulation and transcranial magnetic stimulation are treatment options that have been researched extensively but are not regularly available at this time. These treatments are both supported by strong evidence to be effective for treating neuropathic pain after SCI.

Transcranial electrical stimulation

Transcranial electrical stimulation involves electrodes placed on the scalp to deliver electrical stimulation to areas of the brain that may help to reduce pain.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) involves the use of an electromagnetic coil placed over the head to produce magnetic pulses that stimulate areas of the brain to reduce pain.

Psychological and mind-body therapies are used to address the many non-physical contributors to pain. These can range from treatment from a psychologist or physician to a number of complementary therapies. These treatments have an important and often underused role in pain management. Most of the psychological and mind-body therapies have not been studied extensively for pain after SCI and need further study before we know how effective they are.

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is a psychological therapy that is usually done with a therapist or other health provider. Cognitive behavioural therapy aims to change personal beliefs and coping skills through practices involving thoughts, emotions, and behaviours.

Biofeedback

Biofeedback involves electrically monitoring bodily functions so the individual can learn to regain voluntary control of this function. Electroencephalography (EEG), a non-invasive technology measuring electrical brain activity, has been used to provide feedback on brain states related to chronic pain.

Visual imagery

Visual imagery techniques guide individuals through a series of images to change perceptions and behaviours related to pain.

Hypnosis

Hypnosis is an alternative treatment for chronic pain.

Other treatments

Other psychological and behavioural treatments for chronic pain after SCI, such as meditation, mindfulness, and relaxation techniques, have not yet been studied. Treatments for substance abuse, depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder may also have an important role in pain management.

Surgery for pain is not common and is usually only considered when other treatments have not worked. The risks of surgery should be discussed carefully with your health team before going forward with any procedure. Research on surgery is challenging to conduct and each case is different so support is often based on weak evidence and expert opinion.

Surgery for the cause of the pain

Surgery for the cause of the pain

If the pain has a clear physical cause (such as a spinal instability or a torn muscle) surgery to correct the problem may help to reduce pain. This is done on a case-by-case basis depending on the problem.

Dorsal rhizotomy (DREZ procedure)

Dorsal rhizotomy (DREZ procedure) is a surgical procedure where parts of the nerves close to the spinal cord are cut to interrupt pain signals from being sent to the brain. This is a permanent procedure that can be used for the management of neuropathic pain after SCI.

Myelotomy

Dorsal longitudinal T-myelotomy is a surgical procedure where a small cut is made down the length of a thoracic spinal cord segment to disrupt nerve signals that cause spasticity and pain.

Watch SCIRE’s video about managing pain as you age.

Most people are familiar with the increase in aches and pains as they age. The gradual weakening and degeneration of the muscles, bones, ligaments, and tendons that comes with aging can eventually result in pain. However, the early stages of this degeneration do not usually have obvious symptoms. Pain can also happen because of other health conditions/disease (e.g. cancer, arthritis). Levels of pain can also be affected by mood, stress, and social support of family and friends.

Aging and pain in SCI

Nerve (or neuropathic) pain is the most common type of pain after an SCI. There is some evidence that in general, neuropathic pain is stable as people with SCI age. However, experiences of neuropathic pain for people with SCI are incredibly varied and individual. Over time, one may experience increases, decreases, or new neuropathic pain.

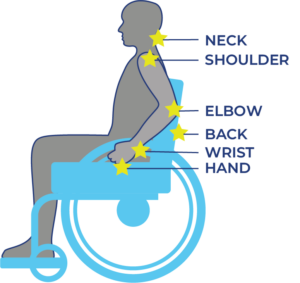

Musculoskeletal pain is caused by problems in the muscles, joints or bones. It is a common problem for all people as they get older, including those with SCI. Most people aging with SCI experience increased musculoskeletal pain in the upper extremities (shoulder and arm). Other common pain spots include the elbows, wrists, and hands. Issues with posture and seating can cause neck and back pain.

Musculoskeletal pain is caused by problems in the muscles, joints or bones. It is a common problem for all people as they get older, including those with SCI. Most people aging with SCI experience increased musculoskeletal pain in the upper extremities (shoulder and arm). Other common pain spots include the elbows, wrists, and hands. Issues with posture and seating can cause neck and back pain.

Overuse injuries develop with age from many years of transfers, pressure relief maneuvers, wheelchair use, and other movements that require weight-bearing and repetitive strain. Because the upper extremities are not designed for such a high physical load, people develop injuries (e.g., tendonitis, bursitis) and pain from overuse.

Research shows that on average, people with SCI experience more arthritis and joint breakdown in the shoulder than the general population.

Pain is also commonly caused by other aging-related health conditions like osteoarthritis of joints beyond that described of the shoulder, skin breakdown, and constipation, etc.

Refer to our article on Shoulder Injury and Pain for more information!

Managing changes in pain with age

To manage changes in musculoskeletal pain from aging with SCI, consult with your doctor, as well as physical and occupational therapists. They can conduct an injury assessment and help find ways to reduce and prevent pain.

Strategies may include:

- Modifying and optimizing movements and wheelchair skills to prevent injury and reduce pain.

- Strength exercises and stretching to stabilize the shoulder joint and improve muscle imbalances.

- Changes in use of assistive devices and technology to prevent further injury/pain and rest the affected joints/muscles.

- Changes in the work and home environment to reduce effort and pain in daily activities.

- Changes in wheelchair setup for propulsion efficiency and ease.

- Medication to relieve pain.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness.

If experiencing a change in neuropathic pain, consult with a health care provider to determine together what may be causing the change and how to manage it.

Refer to the “What physical treatments are used for pain after SCI?”, and “What psychological and mind-body therapies are used for pain after SCI?” sections above for more information on managing pain.

Pain is a common health concern following spinal cord injury and can come from various parts of the body such as: muscle, joints, organs, skin, and nerves. Options such as physical treatment, psychological treatment, medication related treatment, or surgical treatments can be implemented for pain management.

While managing pain can be challenging, working with your health professionals to find a plan that works for you is an effective strategy for adjusting to life with an SCI.

For a review of how we assess evidence at SCIRE Community and advice on making decisions, please see SCIRE Community Evidence.

Mehta S, Teasell RW, Loh E, Short C, Wolfe DL, Hsieh JTC (2014). Pain Following Spinal Cord Injury. In Eng JJ, Teasell RW, Miller WC, Wolfe DL, Townson AF, Hsieh JTC, Connolly SJ, Noonan VK, Loh E, McIntyre A, editors. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence. Version 5.0: p 1-79.

Available from: https://scireproject.com/evidence/pain-management/

Merskey H, Bogduk N, IASP Task Force on Taxonomy. Part III: Pain Terms, a Current List with Definitions and Notes on Usage. In: Merskey H, Bogduk N, (eds). Classification of chronic pain. Seattle: IASP Press;1994: 209–214.

Bryce TN, Biering-Sorensen F, Finnerup NB, Cardenas DD, Defrin R, Lundeberg T, Norrbrink C, Richards JS, Siddall P, Stripling T, Treede RD, Waxman SG, Widerström-Noga E, Yezierski RP, Dijkers M. International spinal cord injury pain classification: Part I. Background and description. March 6-7, 2009. Spinal Cord. 2012;50(6):413-7.

Loh E, Guy SD, Mehta S, Moulin DE, Bryce TN, Middleton JW, Siddall PJ, Hitzig SL, Widerström-Noga E, Finnerup NB, Kras-Dupuis A, Casalino A, Craven BC, Lau B, Côté I, Harvey D, O’Connell C, Orenczuk S, Parrent AG, Potter P, Short C, Teasell R, Townson A, Truchon C, Bradbury CL, Wolfe D. The CanPain SCI clinical practice guidelines for rehabilitation management of neuropathic pain after spinal cord: introduction, methodology and recommendation overview. Spinal Cord. 2016 Aug;54 Suppl 1:S1-6.

Ragnarsson KT. Management of pain in persons with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord Med 1997;20:186-99.

Rose M, Robinson JE, Ells P, Cole JD. Letter to the editor. Pain following spinal cord injury: Results from a postal survey. Pain 1988;34:101-2.

Widerström-Noga EG, Turk DC. Types and effectiveness of treatments used by people with chronic pain associated with spinal cord injuries: Influence of pain and psychosocial characteristics. Spinal Cord 2003;41:600-9.

Norrbrink Budh C, Lundeberg T. Non-pharmacological pain-relieving therapies in individuals with spinal cord injury: A patient perspective. Complement Ther Med. 2004;12:189-97.

Mehta S, Guy S, Lam T, Teasell R, Loh E. Antidepressants Are Effective in Decreasing Neuropathic Pain After SCI: A Meta-Analysis. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation. 2015;21(2):166-173. doi:10.1310/sci2102-166.

Wollaars MM, Post MW, van Asbeck FW, Brand N. Spinal cord injury pain: the influence of psychologic factors and impact on quality of life. Clin J Pain. 2007 Jun;23(5):383-91.

Craig A, Tran Y, Siddall P, Wijesuriya N, Lovas J, Bartrop R, Middleton J. Developing a model of associations between chronic pain, depressive mood, chronic fatigue, and self-efficacy in people with spinal cord injury. J Pain. 2013 Sep;14(9):911-20. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.03.002. Epub 2013 May 23.

Raichle KA, Hanley M, Jensen MP, Cardenas DD. Cognitions, coping, and social environment predict adjustment to pain in spinal cord injury. J Pain. 2007 Sep;8(9):718-29. Epub 2007 Jul 5.

Davidoff G, Roth E, Guarracini M, Silwa J, Yarkony G. Function-limiting dysesthetic pain syndrome among traumatic spinal cord injury patients: a cross-sectional study. Pain 1987; 29: 39–48.

Cohen M, McArthur D, Vulpe M, Schandler S, Gerber K. Comparing chronic pain from spinal cord injury to chronic pain of other origins. Pain 1988; 35: 57–63.

Rose M, Robinson J, Ells P, Cole J. Pain following spinal cord injury: results from a postal survey. Pain 1988; 34: 101–102.

Britell C, Mariano A. Chronic pain in spinal cord injury. Phys Med Rehabil 1991; 5: 71–82.

Mariano A. Chronic pain and spinal cord injury. Clin J Pain. 1992; 8: 87–92.

Cairns D, Adkins R, Scott M. Pain and depression in acute traumatic spinal cord injury: origins of chronic problematic pain? Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1996; 77: 329–335.

Modirian E, Pirouzi P, Soroush M, Karbalaie-Esmaeili S, Shojaei H, Zamani H. Chronic pain after spinal cord injury: results of a long-term study. Pain Med 2010; 11: 1037–1043

Burke DC, Woodward JM. Pain and phantom sensations in spinal paralysis. In Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW (Eds). Handbook of Clinical Neurology (pp. 489-499). Amsterdam, North Holland Publishing Co. 1976.

Rose M, Robinson JE, Ells P, Cole JD. Letter to the editor. Pain following spinal cord injury: Results from a postal survey. Pain 1988;34:101-2.

Turner JA, Cardenas DD, Warms CA, McClellan CB. Chronic pain associated with spinal cord injuries: A community survey. Arch Phys Med Rehab 2001;82:501-9.

Ahn SH, Park HW, Lee BS, Moon HW, Jang SH, Sakong J, et al. Gabapentin effect on neuropathic pain compared among patients with spinal cord injury and different durations of symptoms. Spine 2003;28:341-6.

Moulin DE, Clark AJ, Gilron I, Ware MA, Watson CPN, Sessle BJ, et al. Pharmacological management of chronic neuropathic pain. Consensus statement and guidelines from the Canadian pain society. Pain Res Manag 2007;12:13-21.

To TP, Lim TC, Hill ST, Frauman AG, Cooper N, Kirsa SW, et al. Gabapentin for neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2002;40:282-5.

Tai Q, Kirshblum S, Chen B, Millis S, Johnston M, DeLisa JA. Gabapentin in the treatment of neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury: A prospective, randomized, double-blind, crossover trial. J Spinal Cord Med 2002;25:100-5.

Levendoglu F, Ogun CO, Ozerbil O, Ogun TC, Ugurlu H. Gabapentin is a first line drug for the treatment of neuropathic pain in spinal cord injury. Spine 2004;29:743-51.

Siddall PJ, Cousins MJ, Otte A, Griesing T, Chambers R, Murphy TK. Pregabalin in central neuropathic pain associated with spinal cord injury: A placebo-controlled trial. Neurol 2006;67:1792-800.

Arienti C, Daccò S, Piccolo I, Redaelli T. Osteopathic manipulative treatment is effective on pain control associated to spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2011;49:515-9.

Cardenas DD, Nieshoff EC, Suda K, Goto S, Sanin L, Kaneko T, Spom J, Parsons B, Soulsby M, Yang R, Whalen E, Scavone J, Suzuki M, Knapp L. A randomized trial of pregabalin in patients with neuropathic pain due to spinal cord injury. Neurology. 2013;80:533-39.

Sandford PR, Lindblom LB, Haddox JD. Amitriptyline and carbamazepine in the treatment of dysesthetic pain in spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehab 1992;73:300-1.

Cardenas DD, Warms CA, Turner JA, Marshall H, Brooke MM, Loeser JD. Efficacy of amitriptyline for relief of pain in spinal cord injury: results of a randomized controlled trial. Pain 2002;96:365-73.

Vranken JH, Hollmann MW, Van der Vegt MH, Kruis MR, Heesen M, Vos K, et al. Duloxetine in patients with central neuropathic pain caused by spinal cord injury or stroke: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pain 2011;152:267-73.

Rintala DH, Holmes SA, Courtade D, Fiess RN, Tastard LV, Loubser PG. Comparison of the effectiveness of amitriptyline and gabapentin on chronic neuropathic pain in persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehab 2007;88:1547-60.

Hocking G, Cousins MJ. Ketamine in chronic pain management: An evidence-based review. Anesth Analg 2003;97:1730-9.

Loubser PG, Donovan WH. Diagnostic spinal anaesthesia in chronic spinal cord injury pain. Paraplegia 1991;29:36.

Kvarnstrom A, Karlsten R, Quiding H, Gordh T. The analgesic effect of intravenous ketamine and lidocaine on pain after spinal cord injury. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2004;48:498-506.

Eide PK, Stubhaug A, Stenehjem AE. Central dysethesia pain after traumatic spinal cord injury dependent on N-Methyl-Diaspartate receptor activation. Neurosurgery 1995;37:1080-7.

Herman RM, D’Luzansky SC, Ippolito R. Intrathecal baclofen suppresses central pain in patients with spinal lesions: A pilot study. Clin J Pain 1992;8:338-45.

Boviatsis EJ, Kouyialis AT, Korfias S, Sakas DE. Functional outcome of intrathecal baclofen administration for severe spasticity. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2005;107:289-95.

Plassat R, Perrouin Verbe B, Menei P, Menegalli D, Mathé JF, Richard I. Treatment of spasticity with intrathecal baclofen administration: Long-term follow-up, review of 40 patients. Spinal Cord 2004;42:686-93.

Loubser PG, Akman NM. Effects of intrathecal baclofen on chronic spinal cord injury pain. J Pain Symptom Manage 1996;12:241-7.

Uchikawa K, Toikawa H, Liu M. Subscapularis motor point block for spastic shoulders in patients with cervical cord injury. Spinal Cord 2009;47:249-51.

Marciniak C, Rader L, Gagnon C. The use of botulinum toxin for spasticity after spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehab 2008;87:312-7.

Attal N, Guirimand F, Brasseur L, Gaude V, Chauvin M, Bouhassira D. Effects of IV morphine in central pain: a randomized placebo-controlled study. Neurol 2002;58:554-63.

Norrbrink C, Lundeberg T. Tramadol in neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin J Pain 2009;25:177-84.

Eide PK, Stubhaug A, Stenehjem AE. Central dysethesia pain after traumatic spinal cord injury dependent on N-Methyl-Diaspartate receptor activation. Neurosurgery 1995;37:1080-7.

Hagenbach U, Luz S, Ghafoor N, Berger JM, Grotenhermen F, Brenneisen R et al. The treatment of spasticity with delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol in persons with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2007;45:551-62.

Rintala DH, Fiess RN, Tan G, Holmes SA, and Bruel BM. Effect of dronabinol on central neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury: A pilot study. Am J Phys Med Rehab 2010;89:840-8.

Siddall PJ, Molloy AR, Walker S, Mather LE, Rutkowski SB, Cousins MJ. The efficacy of intrathecal morphine and clonidine in the treatment of pain after spinal cord injury. Anesth Analg 2000;91:1493-8.

Uhle EI, Becker R, Gatscher S, Bertalanffy H. Continuous intrathecal clonidine administration for the treatment of neuropathic pain. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg 2000;75:167-75.

Sandford PR, Benes PS. Use of capsaicin in the treatment of radicular pain in spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2000;23:238-43.

Norrbrink Budh C, Lundeberg T. Non-pharmacological pain-relieving therapies in individuals with spinal cord injury: A patient perspective. Complement Ther Med. 2004;12:189-97.

Chase T, Jha A, Brooks CA, Allshouse A: A pilot feasibility study of massage to reduce pain in people with spinal cord injury during acute rehabilitation. Spinal Cord 2013;51:847-51.

Norrbrink C, Lundeberg T. Acupuncture and massage therapy for neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury: An exploratory study. Acupunc Med 2011;29:108-15.

Arienti C, Daccò S, Piccolo I, Redaelli T. Osteopathic manipulative treatment is effective on pain control associated to spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2011;49:515-9.

Dyson-Hudson TA, Shiflett SC, Kirshblum SC, Bowen JE, Druin EL. Acupuncture and trager psychophysical integration in the treatment of wheelchair user’s shoulder pain in individuals with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehab 2001;82:1038-46.

Dyson-Hudson TA, Kadar P, LaFountaine M, Emmons R, Kirshblum SC, Tulsky D et al. Acupuncture for chronic shoulder pain in persons with spinal cord injury: a small-scale clinical trial. Arch Phys Med Rehab 2007;88:1276-83.

Yeh ML, Chung YC, Chen KM, Tsou MY, and Chen HH. Acupoint electrical stimulation reduces acute postoperative pain in surgical patients with patient-controlled analgesia: A randomized controlled study. Altern Ther Health Med 2010;16:10.

Ginis KAM, Latimer AE, McKechnie K, Ditor DS, Hicks AL, Bugaresti J. Using exercise to enhance subjective well-being among people with spinal cord injury: The mediating influences of stress and pain. Rehab Psychol 2003;48:157-64.

Nawoczenski DA, Ritter-Soronen JM, Wilson CM, Howe BA, Ludewig PM. Clinical trial of exercise for shoulder pain in chronic spinal injury. Phys Ther 2006;86:1604-18.

Serra-Ano P, Pellicer-Chenoll M, Garcia-Masso X, Morales J, Giner-Pascual M, Gonzalez LM: Effects of resistance training on strength, pain and shoulder functionality in paraplegics. Spinal Cord 2012;50:827-831.

Jensen MP, Barber J, Romano JM, Hanley MA, Raichle KA, Molton IR, et al. Effects of self-hypnosis training and EMG biofeedback relaxation training on chronic pain in persons with spinal-cord injury. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 2009;57,239-68.

Jensen MP, Barber J, Williams-Avery RM, Flores L, Brown MZ. The effect of hypnotic suggestion on spinal cord injury pain. J Back Musculoskeletal Rehab 2000;14:3-10.

Jensen MP, Gertz KJ, Kupper AE, Braden AL, Howe JD, Hakimian S, Sherlin LH: Steps toward developing an EEG biofeedback treatment for chronic pain. App Psychophysiol Biofeedback 2013;38:101-8.

Perry KN, Nicholas MK, Middleton JW. Comparison of a pain management program with usual care in a pain management center for people with spinal cord injury-related chronic pain. Clin J Pain 2010;26:206-16.

Heutink M, Post MWM, Bongers-Janssen HMH, Dijkstra CA, Snoek GJ, Spijkerman DCM, Lindeman E: The CONECSI trial: Results of a randomized controlled trial of a multidisciplinary cognitive behavioral program for coping with chronic neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. Pain 2012;153:120-8.

Norrbrink Budh C, Kowalski J, Lundeberg T. A comprehensive pain management programme comprising educational, cognitive and behavioural interventions for neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury. J Rehab Med 2006;38:172-80.

Burns AS, Delparte JJ, Ballantyne EC, Boschen KA: Evaluation of an interdisciplinary program for chronic pain after spinal cord injury. Physical Medicine and Rehab 2013;5:832-8.

Soler MD, Kumru H, Pelayo R, Vidal J, Tormos JM, Fregni F, et al. Effectiveness of transcranial direct current stimulation and visual illusion on neuropathic pain in spinal cord injury. Brain 2010;133:2565-77.

Kumru H, Soler D, Vidal J, Tormos JM, Pascual-Leone A, Valls-Sole J. Evoked potentials and quantitative thermal testing in spinal cord injury patients with chronic neuropathic pain. Clinical Neurophysiology 2012;123:55-66.

Gustin SM, Wrigley PF, Gandevia SC, Middleton JW, Henderson LA, Siddall PJ. Movement imagery increases pain in people with neuropathic pain following complete thoracic spinal cord injury. Pain 2008;137:237-44.

Moseley GL. Using visual illusion to reduce at-level neuropathic pain in paraplegia. Pain 2007;130:294-8.

Capel ID, Dorrell HM, Spencer EP, Davis MW. The amelioration of the suffering associated with spinal cord injury with subperception transcranial electrical stimulation. Spinal Cord 2003;41:109-17.

Fregni F, Gimenes R, Valle AC, Ferreira MJ, Rocha RR, Natalle L et al. A randomized, sham-controlled, proof of principle study of transcranial direct current stimulation for the treatment of pain in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:3988-98.

Soler MD, Kumru H, Pelayo R, Vidal J, Tormos JM, Fregni F, et al. Effectiveness of transcranial direct current stimulation and visual illusion on neuropathic pain in spinal cord injury. Brain 2010;133:2565-77.

Tan G, Rintala DH, Thornby JI, Yang J, Wade W, Vasilev C. Using cranial electrotherapy stimulation to treat pain associated with spinal cord injury. J Rehab Res Dev 2006;43:461-74.

Davis R, Lentini R. Transcutaneous nerve stimulation for treatment of pain in patients with spinal cord injury. Surg Neurol 1975;4:100-1.

Jette F, Cote I, Meziane HB, Mercier C: Effect of single-session repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation applied over the hand versus leg motor area on pain after spinal cord injury. Neurorehabi Neural Repair 2013;27:636-643.

Defrin R, Grunhaus L, Zamir D, Zeilig G. The effect of a series of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulations of the motor cortex on central pain after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehab 2007;88:1574-80.

Cioni B, Meglio M, Pentimalli L, Visocchi M. Spinal cord stimulation in the treatment of paraplegic pain. J Neurosurg 1995;82:35-9.

Livshits A, Rappaport ZH, Livshits V, Gepstein R. Surgical treatment of painful spasticity after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2002;40:161-6.

Falci S, Best L, Bayles R, Lammertse D, Starnes C. Dorsal root entry zone microcoagulation for spinal cord injury-related central pain: operative intramedullary electrophysiological guidance and clinical outcome. J Neurosurg Spine 2002;97:193-200.

Chun HJ, Kim YS, Yi HJ. A modified microsurgical DREZotomy procedure for refractory neuropathic pain. World Neurosurgery 2011;75:551-7.

Sindou M, Mertens P, Wael M. Microsurgical DREZotomy for pain due to spinal cord and/or cauda equina injuries: long-term results in a series of 44 patients. Pain 2001;92:159-71.

Spaic M, Petkovic S, Tadic R, Minic L. DREZ surgery on conus medullaris (after failed implantation of vascular omental graft) for treating chronic pain due to spine (gunshot) injuries. Acta Neurochirurgica 1999;141:1309-12.

Spaic M, Markovic N, Tadic R. Microsurgical DREZotomy for pain of spinal cord and cauda equina injury origin: Clinical characteristics of pain and implications for surgery in a series of 26 patients. Acta Neurochirurgica 2002;144:453-62.

Rath SA, Seitz K, Soliman N, Kahamba JF, Antoniadis G, Richter HP. DREZ coagulations for deafferentation pain related to spinal and peripheral nerve lesions: Indication and results of 79 consecutive procedures. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg 1997;68:161-7.

Sampson JH, Cashman RE, Nashold BS, Jr., Friedman AH. Dorsal root entry zone lesions for intractable pain after trauma to the conus medullaris and cauda equina. J Neursurg 1995;82:28-34.

Nashold BS, Jr., Vieira J, el-Naggar AO. Pain and spinal cysts in paraplegia: Treatment by drainage and DREZ operation. Br J Neurosurg 1990;4:327-35.

Friedman AH, Nashold BS. DREZ lesions for relief of pain related to spinal cord injury. J Neurosurgery 1986;65:465-9.

Image credits

- Wrist pain ©Injurymap, CC BY-SA 4.0

- ©OpenStax College, CC BY 3.0

- Image ©SCIRE, CC BY-NC 4.0

- Image ©SCIRE, CC BY-NC 4.0

- Image ©SCIRE, CC BY-NC 4.0

- ©Intermedichbo, CC BY-SA 4.0

- Assorted Medications ©NIAID, CC BY 2.0

- Treatment ©Royal@design, CC BY 3.0 US

- Back Pain ©Matt Wasser, CC BY 3.0 US

- _DSC0452_19632© ©Eric Neitzel, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

- Her handiwork ©thepismire, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

- Neuro-ms ©Baburov, CC BY-SA 4.0

- PhysiologyLab2009-07 ©Fredric Shaffer, CC0 1.0

- Surgery ©Healthcare Symbols, CC0 1.0

- Aging With Pain Thumbnail ©SCIRE, CC BY-NC 4.0

- Aging Pain Points ©SCIRE, CC BY-NC 4.0