Author: SCIRE Community Team | Reviewer: Susan Andrews | Published: 3 November 2017 | Updated: ~

Key Points

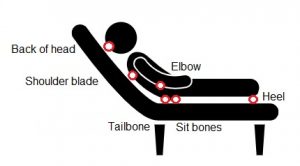

- A pressure injury (or pressure ulcer, wound, or sore) is damage to the skin and underlying tissues caused by pressure, friction, or shear. Pressure injuries are common on weight-bearing areas of the body like the sit bones and tailbone.

- Pressure injuries are a common complication of SCI that can have serious consequences including reduced independence and life-threatening infections.

- People with SCI are at greater risk of developing pressure injuries because of changes to the body and how it is used after SCI.

- Preventing pressure injuries is very important and involves checking the skin regularly, pressure relief, staying healthy, and early treatment of potential injuries.

- The most important factor in treating a pressure injury is identifying and removing the cause of the injury.

- Pressure injuries are treated using several treatments, including wound care and dressings, medications, electrical and light stimulation, debridement, and surgery.

A pressure injury (also known as pressure wound, pressure ulcer or bed sore) is a breakdown of the skin and the tissues under the skin that is caused by pressure, friction, or shear.

Pressure injuries are a common complication of SCI that happens because of changes to the body and how it is used after the injury. Pressure injuries usually happen on areas of the body that bear weight in sitting or lying, such as the sit bones, tailbone, heels, back of the knees, elbows, and shoulder blades.

Pressure injuries are common

Pressure injuries are common after SCI. They can affect as many as one third of people with SCI each year and almost every person with an SCI experiences at least one pressure injury in their lifetime. The risk of pressure injuries increases over time when living with an SCI long-term.

Pressure injuries can have serious consequences

Pressure injuries can have serious consequences for health, function, and quality of life, including:

- Difficult and lengthy healing

- Infections, including severe infections that lead to a life-threatening condition called sepsis

- Long and costly hospital stays and re-hospitalizations

- Reduced independence and mobility during healing

- Inability to participate in work and school during healing

- Reduced life satisfaction and quality of life

- A greater need for assistance from caregivers and family during healing

Prevention is essential to reduce risk

The best management for pressure injuries is prevention. In fact, many pressure injuries are preventable through a combination of good self-care, staying healthy, and regular check-ins with your health team. It is essential to learn how to recognize, prevent, and treat pressure injuries as soon as possible after SCI to help reduce your risk.

Find out what advice Josh has on pressure sores and routines you can follow to avoid them.

Pressure injuries happen because of many different factors from both inside and outside the body. There are a number of changes to the body after SCI that make pressure injuries more likely. These factors, combined with forces like pressure, friction, and shear, can cause pressure injury.

Pressure

Pressure injuries usually form on weight-bearing areas of the body that are in contact with supporting surfaces. This usually happens when sitting or lying in the same position for a long time or when positioned on a surface that does not support the weight properly (such as a hard chair).

Pressure usually happens in specific areas depending on the position, but most often affects the sit bones (ischial tuberosities), tailbone (sacrum and coccyx), heels, backs of the knees, elbows, back of the head, and shoulder blades.

Too much pressure can prevent blood from reaching the area, which is important for bringing oxygen and nutrients to the tissues. This can lead to skin damage or breakdown. Skin breakdown can happen quite quickly (in even 30 to 60 minutes) on a hard surface without changing positions regularly.

Friction and shear

Pressure injuries can also be caused by friction and shear. Friction can happen when the skin is rubbed on a course surface, such as sitting on an uneven wrinkle of clothing or rough surface. This can cause injury to the surface of the skin which can lead to skin breakdown.

Shear is a type of force where the skin goes one way and the body goes the opposite direction. This usually happens when the skin is caught on a surface while the body is moved. For example, when transferring in bed, the skin might be pulled along the bed while the person shifts positions, which causes shear. Shear strains and injures the tissues close to the bone.

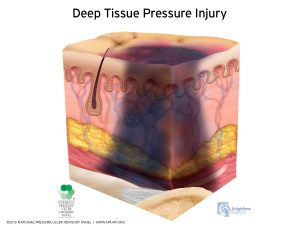

Most pressure injuries result from combinations of pressure, friction, and shear that happen in the deep tissues close to the bone. This leads to deep tissue injury, rather than injury on the skin’s surface.

There are many other factors from both inside and outside the body after SCI that make pressure injuries more likely to develop.

Other factors that contribute to pressure injuries

Changes to the skin

Spinal cord injury can affect the skin in various ways. The skin below the injury may become less elastic and weaker as a result of tissue changes caused by the SCI. In addition, people with injuries above T6 lose the ability to sweat below the injury, which means that body temperature is not regulated very well.

Loss of sensation

Sensation is important because it allows us to recognize discomfort and provides a cue to change position regularly. When sensation is reduced or absent, these cues are not present and we may sit in an uncomfortable position where there is too much pressure for too long.

Loss of movement

Loss of movement also contributes to pressure injuries. People with reduced movement often use a wheelchair as their main method of mobility, which may lead to long periods of sitting in one position. It may also be more difficulty to reposition in sitting or lying so pressure may be placed in one area for too long. As well, when the muscles are not used regularly, they shrink (called muscle atrophy), which means there is less padding between the skin and bone.

Hear Peter speak about his difficulties with not having sensation to his elbows.

Moisture

Moisture makes the skin more vulnerable to injury and bacteria. Moisture may be present because of bladder or bowel problems after an SCI or in warm and humid climates.

Body weight

Changes to body weight, either being too thin or overweight, can increase the risk of pressure injuries. When a person is underweight, there is less padding between the skin and bone. When a person is overweight, the body is heavier, which creates more pressure in weight-bearing and can also make transfers more difficult, which may result in more shearing and friction.

Supporting surfaces

The characteristics of surfaces that support the body in regular positions are very important for distributing pressure. This includes wheelchair cushions, mattresses, couch cushions, car seats, commode or toilet seats, sports equipment, and any other surface that is regularly used for supporting the body. Hard or unsupportive surfaces can contribute to developing pressure injuries. It is important to also consider surfaces in unfamiliar settings, such as when travelling or when a hospital visit is needed. Airplane seats and hospital stretchers do not often provide enough protection for your skin following SCI and you may need a lightweight travel cushion when travelling or to request a specialized surface if you need to visit a hospital.

The characteristics of surfaces that support the body in regular positions are very important for distributing pressure. This includes wheelchair cushions, mattresses, couch cushions, car seats, commode or toilet seats, sports equipment, and any other surface that is regularly used for supporting the body. Hard or unsupportive surfaces can contribute to developing pressure injuries. It is important to also consider surfaces in unfamiliar settings, such as when travelling or when a hospital visit is needed. Airplane seats and hospital stretchers do not often provide enough protection for your skin following SCI and you may need a lightweight travel cushion when travelling or to request a specialized surface if you need to visit a hospital.

Other factors:

- Reduced ability to fight infections (reduced immune function)

- Other medical conditions like infections, blood clots, spasticity and contractures

- Poor nutrition (especially if there is not enough calories or protein)

- Reduced physical activity

- Smoking

- Long periods of bed rest

- The sit bones (ischial tuberosities) may become flatter over time

- Higher level of injury and complete SCI

- Depression

- Reduced ability to perform behaviours that reduce risk, such as regular pressure relief, good skin care, and skin inspections

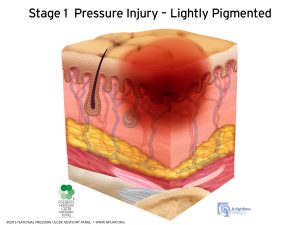

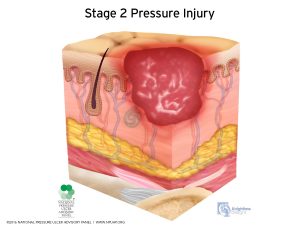

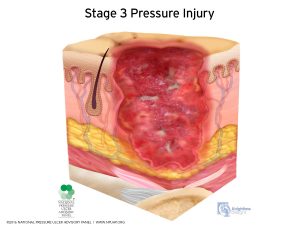

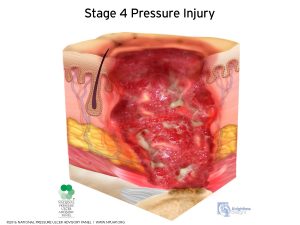

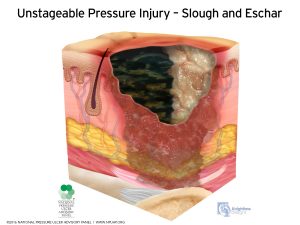

Pressure injuries are classified by how severe they are as “stages” of injury. These stages can range from just a small amount of redness on the skin to a wound that travels all the way down to the bone. Determining which stage a pressure injury is can help you and your health team to measure the extent of wounds and figure out how to treat it.

Stages of Pressure Injury (National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel)2

To identify a pressure injury early you need to check your skin once or twice daily using a mirror or with the help of a care provider.

Physical examination

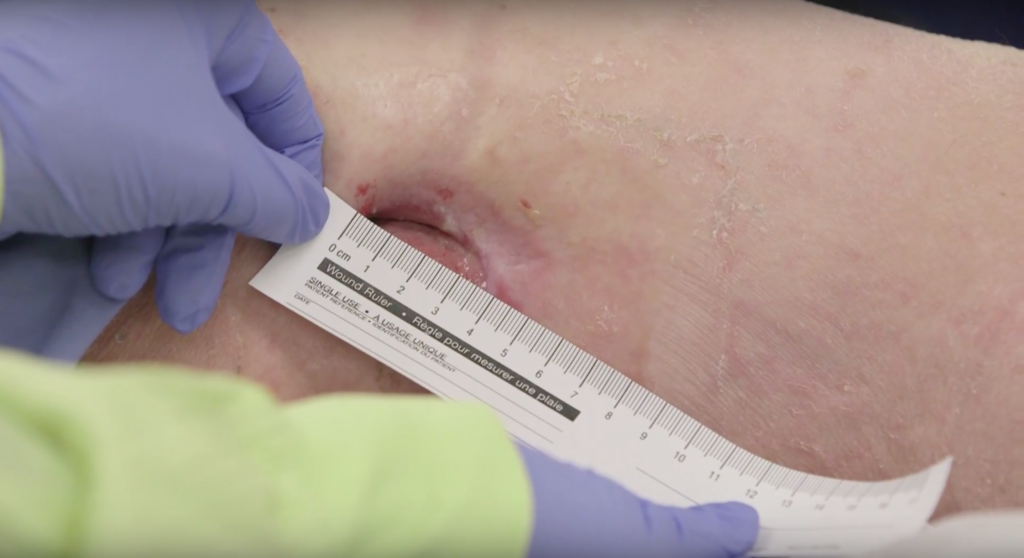

The main way that pressure injuries are diagnosed is with a visual skin check. Checking by feel is not enough, because it only identifies open areas that can be felt. Early pressure injury can be as simple as red or purple discoloration to the skin.

If there is an open wound you may need to be seen by a physician and referred to a nurse for a wound assessment. This may involve starting a treatment plan that should include trying to identify the cause of the pressure injury.

The nurse will observe the wound and take note of its appearance (such as its edges, colour, and shape) and look for signs of inflammation or infection. The nurse may take measurements of the length, width, and depth of the wound. These can help determine the stage of the wound and be used as a comparison as it heals. Sometimes, the nurse may take photos for assessment purposes. A swab of the pressure sore is only taken if infection is suspected. Infection is suspected if there has been increased redness, odour or drainage or if pain has increased if you have sensation.

It is often helpful to have an occupational therapist or physiotherapist involved to help figure out the cause of tissue damage.

Listen to Josh describe his experience of having a pressure sore he wasn’t aware of and how he overcame it with the help of a specialist.

Other testing

- Blood tests may be used to identify if there is an infection.

- Ultrasound is an imaging technique that may be used in some facilities. Ultrasound imaging uses sound waves to detect injuries deep within the skin. It may be used to detect suspected pressure injuries that are not easily seen.

Osteomyelitis (bone infection)

When pressure injuries are severe and reach all the way to the bone (stage 4), there is a risk of developing a serious bone infection called osteomyelitis. If your health team is concerned that you might have osteomyelitis, you may have additional testing such as x-rays, an MRI, or blood tests to diagnose this condition.

The most important part of managing pressure injuries is preventing them from happening in the first place. Many different techniques may be used to prevent pressure injuries. Some of these are a part of self-care and others involve working together with your health team.

Learning how to prevent pressure injuries

Early on in your care, your health providers will speak to you about how to prevent pressure injuries. This may be a part of one-on-one care or as a part of a group education class. Prevention education is a very important part of reducing risk. You will learn how to identify skin concerns early on and the best techniques for you to keep your skin healthy.

Maintaining good skin care

Regular skin care is an important part of preventing pressure injuries. Many of these techniques you will learn as a part of skincare education.

Regular skin checks

Checking the skin for changes in color and texture is important to recognize areas of risk and to identify any changes early. The main areas to check are bony areas, like the sit bones, tail bone, side of the hips, and heels. A mirror or assistance from a caregiver may be needed to check some areas. Any areas of redness, bruising, or injury should be discussed with your health providers immediately. Skin checks are recommended once or twice daily or after activities like prolonged bed rest or trying new equipment.

Listen to Peter describe how he regularly checks his elbows to maintain good skin health.

Keeping the skin healthy

Regular skin care should be done using a gentle pH-balanced skin cleanser and moisturizer. The skin should always be treated gently and not rubbed or massaged forcefully The skin should be kept dry using loose fitting clothes made of light weight fabrics and protecting the skin from excess moisture. Avoid clothing with thick seams or pockets like denim that can contribute to tissue damage.

Regular skin care should be done using a gentle pH-balanced skin cleanser and moisturizer. The skin should always be treated gently and not rubbed or massaged forcefully The skin should be kept dry using loose fitting clothes made of light weight fabrics and protecting the skin from excess moisture. Avoid clothing with thick seams or pockets like denim that can contribute to tissue damage.

Regular pressure relief

Pressure relief techniques are positions and movements that remove pressure and give the tissues a chance to regain proper blood flow. You should discuss with your health providers about which positions are best for you and how often and for how long they should be done for. Keep in mind that moving into pressure relieving positions should not involve pulling or shearing of the skin while re-positioning.

Depending on your level of injury, some people are able to re-position themselves or need a small amount of assistance. People with higher level SCI can use the functions of their wheelchairs or equipment to weight shift or may rely more on caregivers and family to provide assistance.

Pressure relief techniques

- For power wheelchair users, tilting or reclining the chair backwards for a period of time

- For manual wheelchair users, techniques such as leaning forward and propping the elbows onto the knees, lifting the buttocks off the seat by straightening your arms on the armrests, or leaning to one side

- When in bed, techniques such as turning every 2-3 hours, placing pillows between knees and behind the back when lying on your side, and using a suitable pressure relieving surface

This is not a complete or instructive list of pressure relief techniques. Speak to your health provider for detailed instructions on how to perform pressure relief techniques. How-to instructions for some techniques are illustrated on the Spinal Cord Essentials website.

Pressure relief is usually recommended every 15 to 30 minutes to replenish blood flow to vulnerable areas of the skin and held for at least 1 to 2 minutes.

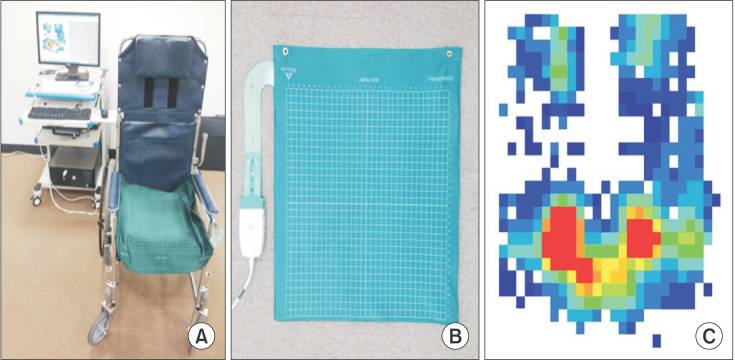

Pressure mapping

Pressure map placed on a wheelchair (left), flexible pressure map (center), and diagram of pressure of a person’s buttocks in sitting (right). Areas of pressure are indicated from high pressures in red (around the sit bones) to lower pressures in blue.11

Pressure mapping is a technique that involves the use of a pressure-sensitive mat and computer system to identify areas of increased pressure. Pressure mapping may help your health provider make recommendations about reducing pressure, including selecting appropriate equipment and finding out which pressure relief positions work best for you.

Using appropriate equipment and seating

Appropriately fitted equipment like wheelchairs, cushions, and bedding can help to maintain healthy skin. During rehabilitation, you may work with your health providers or attend a special clinic where you receive advice on selecting equipment and the correct use of the equipment.

The team will recommend seat cushions, backrests, commodes, and mattresses to help manage pressure in at-risk areas. Regular check-ins at the clinic may also be needed. Most equipment needs to be reviewed and replaced periodically. For example a padded raised toilet seat that has rips or is worn out can be a cause of a pressure injury.

Keeping a healthy lifestyle

Adopting a healthy diet, exercising regularly, and avoiding smoking are simple steps to help maintain healthy skin.

Nutrition

A healthy diet with enough fluids, calories, and protein provides the nutrients and vitamins needed to maintain healthy skin. It also helps in maintaining a healthy body weight. A dietician can help you learn how to eat well to prevent pressure injuries and can advise you on the nutrition you need for healing should you develop a pressure injury.

Avoiding smoking

Smoking is a risk factor for pressure injuries because smoking prevents oxygen from reaching the tissues and worsens overall health.

Smoking is a risk factor for pressure injuries because smoking prevents oxygen from reaching the tissues and worsens overall health.

Exercising regularly

Exercise helps to increase circulation (which carries oxygen and nutrients throughout the body) and maintain overall health. Exercise may also help to maintain muscle bulk which creates padding between the skin and bone.

Electrical stimulation

Although it may seem strange, electrical stimulation is a treatment which may help to prevent pressure injuries. Electrical stimulation on its own can help to increase blood flow and oxygen supply to the body tissues. Electrical stimulation during exercise (functional electrical stimulation) may help to maintain muscle mass that pads areas under the skin.

Many people avoid doing regular pressure injury prevention because it can be time-consuming and difficult. If you are having trouble finding the time to fit these techniques in, it may be time to get support. Speak to your health providers about this issue and see if you can work together to come up with ways that you can make pressure relief and skin care a part of your daily activities so you have enough time to participate in everything that is important to you. Some people find the following tips helpful:

- Make skin care a regular part of your routine, just like brushing your teeth – have everything you needs (a mirror, skin care supplies) easily available where you can use them each day and do your routine at the same time every day

- Ask for help from caregivers and family for help with techniques or reminders to maintain good skin care

- Put a timer on your phone or watch to remind you to shift positions regularly.

Peer support

Many places also have peer support programs where people living with SCI can connect and support one another. Peers can offer firsthand knowledge and experience that may help you find the right techniques for your lifestyle. Online support groups and apps may also help you connect with support from people living with SCI.

Organizations that may offer peer support can be found on our Organizations and Foundations Resource page.

Discover how Peter manages pressure sores with his wound care nurse.

Find out how Josh learns how to take care of his pressure sores at home with his wound care nurse.

There are a number of different treatments for pressure injuries. Treatments may be used to reduce pressure or shearing to the wound, keep the wound clean and protected to reduce the risk of infection, and aid circulation and healing. Treatment for pressure sores is the responsibility of the whole health team, so you may work with many different professionals.

Dressings

Wound dressings help to protect the wound, absorb drainage from the wound, and prevent bacteria from entering while also allowing it to breathe. There are many different types of dressings that may be used for pressure sores. Your nurse will help to decide which dressings to use and how often they need to be changed.

Medications

Antibiotics are used as needed to treat infections in the soft tissues or when osteomyelitis (bone infection) is present. Topical antimicrobial treatments are sometimes applied to the wound to reduce bacteria to try to prevent infection and support healing.

Antibiotics are used as needed to treat infections in the soft tissues or when osteomyelitis (bone infection) is present. Topical antimicrobial treatments are sometimes applied to the wound to reduce bacteria to try to prevent infection and support healing.

Energy-based therapies

A number of different energy-based therapies may also be used to treat pressure injuries. These treatments are done to help increase circulation, kill bacteria, and promote healing.

Electrical stimulation

Electrical stimulation may be applied to pressure injuries through electrodes connected to a small device. Studies suggest that electrical stimulation works to help with healing of severe wounds (stage 3 and 4) after SCI.

Ultraviolet C light

Ultraviolet C light may be applied to a wound using special light bulbs and equipment. Ultraviolet C light has antibacterial effects on wounds. Research suggests that Ultraviolet C is effective for helping treat pressure injuries after SCI.

Debridement

Debridement is a method of removing dead tissue and debris from wounds. There are several methods used to debride wounds and your wound care nurse or physician will choose the method that is right for you. Types of debridement may include:

Surgical debridement by a surgeon under anesthesia

- Sharp debridement using sterile scissors performed by a wound care nurse

- Maggot therapy, which involves using maggots to selectively remove only the dead tissue

- Enzymatic debridement, which involves using enzymes to help dissolve the dead tissue

- Autolytic debridement, when moisture is added to the wound as needed to help the dead tissue debride from the wound

Debridement is only needed if there is slough or unhealthy yellow black tissue in the wound base and should only be done when there is enough circulation for healing to occur.

Flap reconstruction surgery

Surgery may be an option if the wound does not improve with other treatments. This is typically only used for stage 3 or stage 4 injuries. The procedure for closing these wounds is called flap reconstruction surgery. Flap reconstruction involves removing the wound and surrounding tissue and covering it with other nearby tissues, such as muscles and skin. After this type of surgery, careful procedures must be followed before you can get up and moving safely.

Amputation

Amputation may sometimes be necessary if a wound gets severely infected and the infection moves into nearby tissues. This is more commonly seen in legs and feet.

Negative pressure treatments

Negative pressure wound treatments involve the use of a vacuum which applies suction to a wound that is covered with a wound dressing. This helps to manage drainage and increase circulation. A negative pressure dressing should only be used when the wound is clean and pink healthy tissue and when the cause of the pressure injury has been addressed.

Other pressure injury treatments

There are many other medical, alternative, and physical treatments that may be used in the treatment of pressure injuries. Speak to your wound care team about any treatments you are considering trying.

Pressure injuries are a common and serious complication of SCI. Many pressure injuries are largely preventable through a combination of regular skin care, pressure relief, staying healthy, and early treatment of potential injuries.

Treatment of pressure sores may involves wound care, electrical and light stimulation, prevention and treatment of infections that may occur, and surgery for severe wounds. Speak with your health providers to discuss your prevention and treatment options to find out which ones are best for you.

For a review of how we assess evidence at SCIRE Community and advice on making decisions, please see SCIRE Community Evidence.

Parts of this page have been adapted from the SCIRE Professional “Skin Integrity and Pressure Injuries” Module:

Hsieh J, McIntyre A, Wolfe D, Lala D, Titus L, Campbell K, Teasell R. (2014). Pressure Ulcers Following Spinal Cord Injury. In Eng JJ, Teasell RW, Miller WC, Wolfe DL, Townson AF, Hsieh JTC, Connolly SJ, Noonan VK, Loh E, McIntyre A, editors. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence. Version 5.0. 1-90.

Available from: https://scireproject.com/evidence/skin-integrity-and-pressure-injuries/

Adegoke BO, Badmos KA. Acceleration of pressure ulcer healing in spinal cord injured patients using interrupted direct current. Afr J Med Med Sci 2001;30:195-197.

Ahluwalia R, Martin D, Mahoney JL. The operative treatment of pressure wounds: a 10-year experience in flap selection. Int Wound J 2010;7(2):103-106.

Biglari B, Büchler A, Reitzel T, Swing T, Gerner HJ, Ferbert T, Moghaddam A. A retrospective study on flap complications after pressure ulcer surgery in spinal cord-injured patients. Spinal Cord 2014;52:80-83.

Banks, PG, Ho, CH. A novel topical oxygen treatment for chronic and difficult-to-heal wounds: case studies. Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine 2008;31:297-301.

Bauman WA, Spungen AM, Collins JF, Raisch DW, Ho C, Deitrick GA, et al. The effect of oxandrolone on the healing of chronic pressure ulcers in persons with spinal cord injury: a randomized trial. Ann Int Med 2013; 158(10):718-726.

Bergstrom N, Braden BJ, Laguzza A, Holman V. The Braden Scale for Predicting Pressure Sore Risk. Nurs Res 1987;36:205-210.

Bertheuil N, Huguier V, Aillet S, Beuzeboc M, Watier E. Biceps femoris flap for closure of ischial pressure ulcers. Eur J Plast Surg 2013;6(10):639-644.

Biglari B, Büchler A, eitzel T, Swing T, Gerner H J, Ferbert T, et al. Moghaddamspective study on flap complications fter pressure ulcer surgery in spinal cord-injured patients. Spinal cord 2013; 52(1):80-83.

Bogie KM, Ho CH. Pulsatile lavage for pressure ulcer management in spinal cord injury: a retrospective clinical safety review. Ostomy Wound Manage 2013;59(3):35-38.

Bogie KM, Reger SI, Levine SP, Sahgal V. Electrical stimulation for pressure sore prevention and wound healing. Assist Technol 2000;12:50-66.

Bogie KM, Triolo RJ. Effects of regular use of neuromuscular electrical stimulation on tissue health. J Rehabil Res Dev 2003;40:469-475.

Borgognone A, Anniboletti T, De Vita F, Schirosi M, Palombo P. Ischiatic pressure sores: our experience in coupling a split-muscle flap and a fasciocutaneous flap in a ‘criss-cross’ way. Spinal Cord 2010;48(10):770-773.

Brace JA, Schubart JR. A prospective evaluation of a pressure ulcer prevention and management E-learning program for adults with spinal cord injury. Ostomy Wound Management 2010;56(8):40-50.

Brewer S, Desneves K, Pearce L, Mills K, Dunn L, Brown D, et al. Effect of an arginine-containing nutritional supplement on pressure ulcer healing in community spinal patients. J Wound care 2010;19:7:311-316.

Byrne DW, Salzberg CA. Major risk factors for pressure ulcers in the spinal cord disabled: a literature review. Spinal Cord 1996;34:255-263.

Chen W, Jiang B, Zhao J, Wang P. The superior gluteal artery perforator flap for reconstruction of sacral sores. Saudi Med J 2016;37(10):1140-1143.

Coggrave M, West H, Leonard B. Topical negative pressure for pressure ulcer management. Br J Nurs 2002;11(6):29-36.

Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Pressure ulcer prevention and treatment following spinal cord injury: A clinical practice guideline for health care professionals (pp. 1-77). 2000.

Cukjati D, Robnik-Šikonja M, Reberšek S, Kononenko I, Miklavčič D. Prognostic factors in the prediction of chronic wound healing by electrical stimulation. Med and Bio Eng and Comp 2001;39(5):542-550.

de Angelis B, Lucarini L, Agovino A, Migner A, Orlandi F, Floris M, et al. Combined use of super-oxidised solution with negative pressure for the treatment of pressure ulcers: case report. Int Wond J 2013;10(3):36-339.

de Laat EH, van den Boogaard MH, Spauwen PH, van Kppevelt DH, van Goor H, Schoonhoven L. Faster wound healing with topical negative pressure therapy in difficult-to- heal wounds: a prospective randomized control trial. Ann Plast Surg 2011;67(6):626-631.

Erba P, Wettstein R, Schumacher R, Schwenzer-Zimmerer K, Pierer G, Kalbermatten DF. Silicone moulding for pressure sore debridement. J Plast Reconstr Aesthe Surg 2010;63(3):550-553.

Ferguson AC, Keating JF, Delargy MA, Andrews BJ. Reduction of seating pressure using FES in patients with spinal cord injury: a preliminary report. Paraplegia 1992;30(7):474-478.

Fuhrer MJ, Garber SL, Rintala DH, Clearman R, Hart KA. Pressure ulcers in communityresident persons with spinal cord injury: prevalence and risk factors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1993;74(11):1172-1177.

Garber SL, Rintala DH, Holmes SA, Rodriguez GP, Friedman J. A structured educational model to improve pressure ulcer prevention knowledge in veterans with spinal cord dysfunction. J Rehab Res Dev 2002;39(5):575-588.

Grassetti L, Scalise A, Lazzeri D, Carle F, Agostini T, Gesuita R, et al. Perforator flaps in late-stage pressure sore treatment: outcome analysis of 11-year-long experience with 143 patients. Ann Plast Surg 2014;73(6):679-685.

Griffin JW, Tooms RE, Mendius RA, Clifft JK, Vander ZR, El Zeky F et al. Efficacy of high voltage pulsed current for healing of pressure ulcers in patients with spinal cord injury. Phys Ther 1991;71:433-444.

Guihan M, Smith BM, LaVela SL, Garber SL. Factors predicting pressure ulcers in veterans with spinal cord injuries. Amer Journ of Phys Med & Rehab 2008;87(9):750-7.

Gyawali S, Solis L, Chong SL, Curtis C, Seres P, Kornelsen I, et al. Intermittent electrical stimulation redistributes pressure and promotes tissue oxygenation in loaded muscles of individuals with spinal cord injury. Journ Appl Physiol 2011;110(1):246-255

He J, Xu H, Wang T, Ma S, Dong J. Treatment of complex ischial pressure sores with free partial lateral latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flaps in paraplegic patients. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2012;65(5):634-639.

Ho CH, Bensitel T, Wang X, Bogie KM. Pulsatile lavage for the enhancement of pressure ulcer healing: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther 2012;92(1):38-48.

Hollisaz MT, Khedmat H, Yari F. A randomized clinical trial comparing hydrocolloid, phenytoin and simple dressings for the treatment of pressure ulcers [ISRCTN33429693]. BMC Dermatol 2004; 4:18.

Houghton PE, Campbell KE and CPG Panel. Canadian best practice guidelines for the prevention and management of pressure ulcers in people with spinal cord injury: A resource handbook for clinicians. Accessed at http://www.onf.org. 2013.

Houghton PE, Campbell KE, Fraser CH, Harris C, Keast DH, Potter PJ et al. Electrical stimulation therapy increases rate of healing of pressure ulcers in community-dwelling people with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2010;91(5):669-678.

Houlihan BV, Jette A, Friedman AH, Paasche-Orlow M, Ni P, Wierbicky J, et al. A pilot study of a telehealth intervention for persons with spinal cord dysfunction. Spinal Cord 2013;51(9):715– 720.

Jercinovic A, Karba R, Vodovnik L, Stefanovska A, Kroselj P, Turk R, et al. Low frequency pulsed current and pressure ulcer healing. Rehab Eng IEEE Transactions on 1994;2(4):225-233.

Kanno N, Nakamura T, Yamanaka M, Kouda K, Nakamura T, Tajima F. Low-echoic lesions underneath the skin in subjects with spinal-cord injury. Spinal cord 2008;47(3):225-229.

Karba, R., Semrov, D., Vodovnik, L., Benko, H., & Savrin, R. DC electrical stimulation for chronic wound healing enhancement. Part 1. Clinical study and determination of electrical field distribution in the numerical wound model. Bioelectrochemistry and Bioenergetics.1997;43:265-270.

Kaya AZ, Turani N, Akyuz M. The effectiveness of a hydrogel dressing compared with standard management of pressure ulcers. Journal of Wound Care 2005;14:42-44.

Keast DH, Fraser C. Treatment of chronic skin ulcers in individuals with anemia of chronic disease using recombinant human erythropoietin (EPO): a review of four cases. Ostomy Wound Manage 2004;50:64-70.

Kennedy P, Berry C, Coggrave M, Rose L, Hamilton L. The effect of a specialist seating assessment clinic on the skin management of individuals with spinal cord injury. J Tissue Viability 2003;13(3):122-125.

Kierney PC, Cardenas DD, Engrav LH, Grant JH, Rand RP. Limb-salvage in reconstruction of recalcitrant pressure sores using the inferiorly based rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998;102(1):111-116.

Kim JT, Kim YH, Naidu S. Perfecting the design of the gluteus maximus perforator-based island flap for coverage of buttock defects. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010;125(6):1744-1751.

Krause JS. Skin sores after spinal cord injury: relationship to life adjustment. Spinal Cord 1998;36(1):51-56.

Lin H, Hou C, Chen A, Xu Z. Long-term outcome of using posterior-thigh fasciocutaneous flaps for the treatment of ischial pressure sores. J Reconstr Microsurg 2010;26(6):355-358.

Liu X, Meng Q, Song H, Zhao T. A traditional Chinese herbal formula improves pressure ulcers in paraplegic patients: A randomized, parallel-group, retrospective trial. Exp Ther Med 2013;5(6):1693-1696.

Loerakker S, Huisman ES, Seelen HA, Glatz JF, Baaijens FP, Oomens CW, et al. Plasma variations of biomarkers for muscle damage in male nondisabled and spinal cord injured subjects. Journ of Rehab Research and Develop 2012;49(3):361-372.

López de Heredia L, Hauptfleisch J, Hughes R, Graham, A, Meagher TM. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Pressure Sores in Spinal Cord Injured Patients: Accuracy in Predicting Osteomyelitis. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehab 2012;18(2):146-148.

Lui QL, Nicholson GP, Knight SL, Chelvarajah R, Gall A, Middleton FRI, Ferguson-Pell MW, Craggs MD. Pressure changes under the ischial tuberosities of seated individuals during sacral nerve root stimulation. J Rehabil Res Dev 2006;43:209-218.

Lui QL, Nicholson GP, Knight SL, Chelvarajah R, Gall A, Middleton FRI, Ferguson-Pell MW, Craggs MD. Interface pressure and cutaneous hemoglobin and oxygenation changes under ischial tuberosities during sacral nerve root stimulation in spinal cord injury. J Rehabil Res Dev 2006a;43:553-564.

Mawson AR, Siddiqui FH, Connolly BJ, Sharp CJ, Stewart GW, Summer WR, et al. Effect of high voltage pulsed galvanic stimulation on sacral transcutaneous oxygen tension levels in the spinal cord injured. Paraplegia 1993;31(5):311-319.

May L, Day R, Warren S. Evaluation of patient education in spinal cord injury rehabilitation: Knowledge, problem-solving and perceived importance. Disabil Rehabil, 2006;28(7):405–413.

Mehta A, Baker TA, Shoup M, Brownson K, Amde S, Doren E, et al. Biplanar flap reconstruction for pressure ulcers: experience in patients with immobility from chronic spinal cord injuries. Am J Surg 2012;203(3):303-306.

Mortenson WB, Miller WC. A review of scales for assessing the risk of developing a pressure ulcer in individuals with SCI. Spinal Cord 2008;46(3):168-175.

National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: Quick Reference Guide. Emily Haesler (Ed.). Cambridge Media: Osborne Park, Western Australia; 2014.

Nussbaum E, Flett H, McGillivray C. Ultraviolet-C (UVC) improves wound healing in persons with spinal cord injury (SCI). Presented at the International Conference on Spinal Cord Medicine and Rehabilitation in Washington, DC; June 4–8, 2011.

Nussbaum EL, Biemann I, Mustard B. Comparison of ultrasound/ultraviolet-C and laser for treatment of pressure ulcers in patients with spinal cord injury. Phys Ther 1994;74:812-823.

Relander M, Palmer B. Recurrence of surgically treated pressure sores. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg 1988;22(1):89-92.

Rintala DH, Garber SL, Friedman JD, Holmes SA. Preventing recurrent pressure ulcers in veterans with spinal cord injury: impact of a structured education and follow-up intervention. Arch of Phys Med and Rehab 2008;89(8):1429-1441.

Rintala, D. H., Garber, S. L., Friedman, J. D., & Holmes, S. A. Preventing recurrent pressure ulcers in veterans with spinal cord injury: impact of a structured education and follow-up intervention. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2008;89:1429-1441

Salzberg CA, Byrne DW, Cayten CG, van Niewerburgh P, Murphy JG, Viehbeck M. A new pressure ulcer risk assessment scale for individuals with spinal cord injury. Amer Journ Phys Med Rehab 1996;75(2):96-104.

Salzberg CA, Cooper-Vastola SA, Perez F, Viehbeck MG, Byrne DW. The effects of non-thermal pulsed electromagnetic energy on wound healing of pressure ulcers in spinal cord-injured patients: a randomized, double-blind study. Ostomy Wound Manage 1995;41:42-4,46,48.

Scevola S, Nicoletti G, Brenta F, Isernia P, Maestri M, Faga A. Allogenic platelet gel in the treatment of pressure sores: a pilot study. Int Wound J 2010;7(3):184-190.

Schubart J. An E-learning program to prevent pressure ulcers in adults with spinal cord injury: A pre- and post- pilot test among rehabilitation patients following discharge to home. Ostomy Wound Management 2012;58(10):38-49.

Sell SA, Ericksen JJ, Reis TW, Droste LR, Bhuiyan MB, Gater DR. A case report on the use of sustained release platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of chronic pressure ulcers. The Journ of Spinal Cord Med 2011;34(1):122.

Sherman RA, Wyle F, Vulpe M. Maggot therapy for treating pressure ulcers in spinal cord injury patients. J Spinal Cord Med 1995;18:71-74.

Singh R, Singh R, Rohilla RK, Siwach R, Verma V, Kaur K. Surgery for pressure ulcers improves general health and quality of life in patients with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2010;33(4):396-400.

Smit CA, Haverkamp GL, de Groot S, Stolwijk-Swuste JM, Janssen TW. Effects of electrical stimulation-induced gluteal versus gluteal and hamstring muscles activation on sitting pressure distribution in persons with a spinal cord injury. Spinal cord 2012;50(8):590-594.

Smit CA, Legemate KJ, de Koning A, de Groot S, Stolwijk-Swuste JM, Janssen,TW. Prolonged electrical stimulation-induced gluteal and hamstring muscle activation and sitting pressure in spinal cord injury: Effect of duty cycle. Journ of Rehab Res Dev 2013;50(7):1035-1046.

Smit CA, Zwinkels M, van Dijk T, de Groot S, Stolwijk-Swuste JM, Janssen TW. Gluteal blood flow and oxygenation during electrical stimulation-induced muscle activation versus pressure relief movements in wheelchair users with a spinal cord injury. Spinal cord 2013;51(9):694-699.

Srivastava A, Gupta A, Taly AB, Murali T. Surgical management of pressure ulcers during inpatient neurologic rehabilitation: outcomes for patients with spinal cord disease. J Spinal Cord Med 2009;32(2):125-131.

Subbanna, P. K., Margaret Shanti, F. X., George, J., Tharion, G., Neelakantan, N., Durai, S. et al. Topical phenytoin solution for treating pressure ulcers: A prospective, randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:739-743

Taly AB, Sivaraman Nair KP, Murali T, John A. Efficacy of multiwavelength light therapy in the treatment of pressure ulcers in subjects with disorders of the spinal cord: A randomized double-blind controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004;85:1657-1661.

Tavakoli K, Rutkowski S, Cope C, Hassall M, Barnett R, Richards M, et al. Recurrence rates of ischial sores in para- and tetraplegics treated with hamstring flaps: an 8-year study. Br J Plast Surg 1999;52(6):476-479.

Tzen YT, Brienza DM, Karg PE, Loughlin PJ. Effectiveness of local cooling for enhancing tissue ischemia tolerance in people with spinal cord injury. The journal of spinal cord medicine, 2013;36(4):357-364.

Unal C, Ozdemir J, Yirmibesoglu O, Yucel E, Agir H. Use of inferior gluteal artery and posterior thigh perforators in management of ischial pressure sores with limited donor sites for flap coverage. Ann Plast Surg 2012;69(1):67-72.

van Londen A, Herwegh M, van der Zee CH, Daffertshofer A, Smit CA, Niezen A, Janssen TW. The effect of surface electric stimulation of the gluteal muscles on the interface pressure in seated people with spinal cord injury. Arch of Phys Med and Rehab 2008;89(9):1724-1732.

Vesmarovich S, Walker T, Hauber RP, Temkin A, Burns R. Use of telerehabilitation to manage pressure ulcers in persons with spinal cord injuries. Adv Wound Care 1999;12(5):264-269.

Wang SY, Wang JN, Lv DC, Diao YP, Zhang Z. Clinical research on the bio-debridement effect of maggot therapy for treatment of chronically infected lesions. Orthop Surg 2010;2(3):201-206.

Image credits:

- Reprinted with permission of the copyright holder, Gordian Medical, Inc. dba American Medical Technologies (courtesy of National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel)

- Hospital ©Icons Producer, CC BY 3.0

- Modified from: Man Resting on Long Chair ©Gan Khoon Lay, CC BY 3.0

- Image by SCIRE Community Team

- Image by SCIRE Community Team

- Images of pressure ulcer stages used with permission and copyright NPUAP

- Image by SCIRE Community Team

- Image by SCIRE Community Team

- Sweaty-skin ©Jo Andre Johansen, CC BY-SA 2.0

- Image by SCIRE Community Team

- Image from Cho KH, Beom J, Yuk JH, Ahn SC. The Effects of Body Mass Composition and Cushion Type on Seat-Interface Pressure in Spinal Cord Injured Patients. Ann Rehabil Med. 2015 Dec;39(6):971-9. doi: 10.5535/arm.2015.39.6.971. Epub 2015 Dec 29. Published online 2015 Dec 29. doi: 10.5535/arm.2015.39.6.971 (CC BY-NC 4.0)

- CWSC Panthers ©DSC_0284, CC BY-SA 2.0

- Mirror ©Vectors Market, CC BY 3.0

- Pills ©Sketch2SVG, CC BY 3.0

- MEDRETE 16-2 ©US Army Africa. CC BY 2.0