Author: SCIRE Community Team | Reviewers: Shannon Sproule, Tova Plashkes, Amrit Dhaliwal | Published: 17 February 2017 | Updated: 26 March 2024

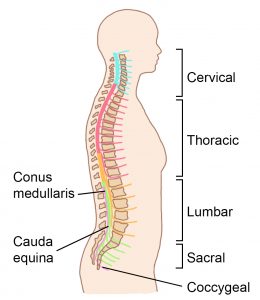

This page provides an overview of background information about spinal cord injury. For information about what the spinal cord is and how it works, see Spinal Cord Anatomy.

Key Points

- Spinal cord injury occurs when the spinal cord or the nerves at the end of the spinal canal are damaged and causes changes to how the body works.

- Spinal cord injury may cause changes in strength, sensation, bladder, bowel and other functions below the injury.

- There are many different types of spinal cord injury and the effects of the injury can be very different from one person to the next.

- The amount of function affected largely depends on where the injury occurs and how severe the damage is.

- Health providers use a standardized physical exam called the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury exam to determine the level of injury and whether the injury is complete or incomplete. This is referred to as the AIS classification.

![]() A spinal cord injury (SCI) occurs when the spinal cord or the nerves at the end of the spinal canal are damaged and causes changes to how the body works.

A spinal cord injury (SCI) occurs when the spinal cord or the nerves at the end of the spinal canal are damaged and causes changes to how the body works.

SCI can be a life-changing injury. It can affect many different body systems and often causes permanent changes to strength, sensation, and other functions below the injury. There are many different types of spinal cord injury and the effects of the injury can be very different from one person to the next.

SCI can have many causes, which are commonly divided into traumatic or non-traumatic causes.

Traumatic spinal cord injury

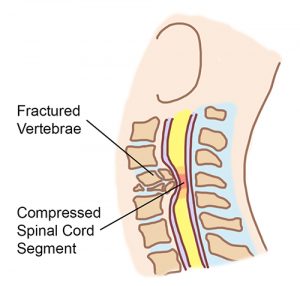

Traumatic spinal cord injury is damage to the spinal cord that is caused by direct trauma from an outside force. This is usually caused by a sudden blow to the spine (such as something falling on the spine), compression of the spine (from the force of a car of a car accident, for example) or a penetrating injury (such as a gunshot wound).

A broken spinal bone (vertebra) in the neck causes pieces of bone or tissue to move out of place, damaging the fragile nearby spinal cord.2

How does damage to the spine cause spinal cord injury?

A forceful blow or compression of the spine can cause the spinal bones (vertebrae) or other tissues (such as the gel-like discs between the vertebrae) to break and/or dislocate. The spinal cord is located within the hollow center of the spine, so if pieces of bone or tissue move out of place and pressure and or excessive swelling take place they can put pressure on, tear, or otherwise damage the fragile spinal cord.

Although a large force is usually needed to damage the spine, smaller forces can also cause traumatic injuries in people with certain medical conditions. For example, people with osteoporosis have weak bones that can break from lesser forces, such as a fall from a standing position.

Non-traumatic spinal cord injury

Non-traumatic spinal cord injury is damage to the spinal cord that is caused by anything other than direct trauma. This includes complications from an illness, degeneration of the spine from arthritis, or certain conditions that people are born with (like spina bifida). Non-traumatic injuries often develop gradually over time, compared to the sudden onset of traumatic injuries.

Read our article on Non-traumatic SCI for more information (coming soon)!

Common causes of spinal cord injury

| Traumatic spinal cord injury | Non-traumatic spinal cord injury |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Spinal cord injury can cause a wide range of different signs and symptoms. The effects of the injury can be very different from one person to the next, depending on the person and the characteristics of the injury. Symptoms can be temporary or permanent and may change over time.

The earliest period after a spinal cord injury often involves a phase of shock. This is usually a temporary period that resolves after a few days or weeks.

Early symptoms of spinal cord injury

Spinal shock happens right after injury and causes the muscles below the injury to be floppy and unmoving (called flaccid paralysis). This happens because the spinal reflexes below the injury are temporarily impaired in response to the injury. Spinal shock often happens together with neurogenic shock.

Spinal shock happens right after injury and causes the muscles below the injury to be floppy and unmoving (called flaccid paralysis). This happens because the spinal reflexes below the injury are temporarily impaired in response to the injury. Spinal shock often happens together with neurogenic shock.

Neurogenic shock is when low blood pressure, slow heart rate, and low body temperature happen early after SCI because of how the injury affects the autonomic nervous system. Neurogenic shock typically affects people with cervical or upper thoracic injuries. If severe and untreated, neurogenic shock can be life-threatening.

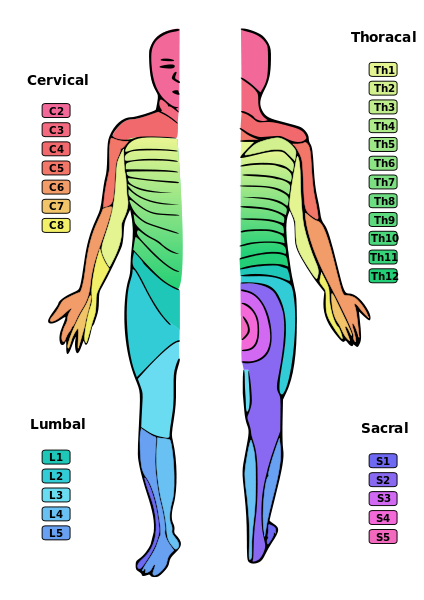

Each level of the spinal cord provides sensation to a different part of the body.4

After shock resolves, the longer-lasting symptoms of spinal cord injury may be experienced. These may include the following symptoms.

Changes in sensation

Changes in sensation occur below the spinal cord injury. This may include total or partial loss of sensation as well as abnormal sensations like tingling, numbness, or pain.

The amount of sensation affected depends on whether the injury is complete or incomplete and the level of the injury. Each level of injury causes changes to the sensation in a specific area of the body. For example, an injury at C3 affects sensation from the neck down, whereas an injury at L1 affects sensation of the legs and groin.

People with incomplete spinal cord injuries may have only parts of their sensation below the injury affected. Those with complete injuries may also have some sensation in select areas below the injury, which are called zones of partial preservation.

Pain below the injury

Pain originating from the spinal cord injury is called neuropathic pain. It can be felt in areas at or below the injury, even if sensation is not present, and is an especially distressing symptom for many people.

Changes in strength and muscle control

Changes to the strength and control of the muscles also happens below the injury. This can include both paralysis (loss of movement) and weakness of the muscles.

The amount of strength and movement affected depends on whether the injury is complete or incomplete and the level of injury. Each level of injury affects specific muscles. For example, an injury at C3 can cause paralysis from the neck down, whereas an injury at L1 can cause paralysis of the hips and legs.

People with incomplete injuries may have strength in some of the muscles below the injury.

Spasticity

Spasticity is a common symptom of spinal cord injury. It involves muscle spasms, muscle tightness or tension, involuntary jerking movements, and overactive reflexes below the injury.

Changes in breathing

People who have cervical and thoracic spinal cord injuries may experience problems with breathing. This is because the diaphragm (the main muscle of breathing), as well as the muscles of the neck, chest, and abdomen are needed to breathe and cough normally. This can affect the ability to breathe, cough, and clear mucus from the lungs without assistance.

Injuries at C5 and above affect the diaphragm and sometimes people with injuries at these levels cannot breathe long-term without the support of a ventilator or other device. People with lower cervical and thoracic injuries may also experience problems breathing because they cannot control other important muscles of the neck and rib cage that help with breathing and coughing.

Read our articles related to Breathing for more information!

Changes in bladder function

There are a number of changes to bladder function after spinal cord injury, including inability to control urination. Many people will use catheters and other treatments to control their bladder functions after spinal cord injury, which may predispose them to developing urinary tract infections if not done carefully.

Read our articles about Bladder Health for more information!

Changes in bowel function

Bowel problems are also common after spinal cord injury and can include an inability to control bowel functions (bowel incontinence), constipation, and other problems. Many people use a personalized bowel routine, which is a schedule that keeps bowels moving at a regular rate (using special foods or supplements), to maintain healthy bowel function after spinal cord injury.

Bowel problems are also common after spinal cord injury and can include an inability to control bowel functions (bowel incontinence), constipation, and other problems. Many people use a personalized bowel routine, which is a schedule that keeps bowels moving at a regular rate (using special foods or supplements), to maintain healthy bowel function after spinal cord injury.

Read our article about Bowel Changes After SCI for more information!

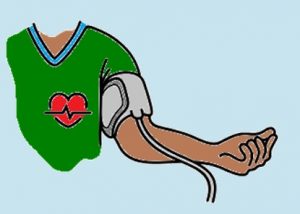

Changes in control of blood pressure and heart rate

The autonomic nervous system is part of the nervous system that controls the unconscious functions of the internal organs like the heart and circulation (blood vessels). Spinal cord injury can cause changes to how the autonomic nervous system functions, which may alter the body’s ability to control blood pressure, temperature, and heart rate, as well as cause conditions like orthostatic hypotension (a sudden drop in blood pressure when moving into an upright position) and autonomic dysreflexia.

Read our article about Orthostatic Hypotension for more information!

Autonomic dysreflexia

Autonomic dysreflexia is a potentially dangerous, sudden increase in blood pressure that can happen in in people with injuries at T6 and above. It can cause symptoms like headaches, sweating, and flushing. Autonomic dysreflexia is a medical emergency.

Read our article about Autonomic Dysreflexia for more information!

Changes in sexual function

Changes in sexual function are also common after spinal cord injury. This may include difficulties with orgasm, ejaculation, and erection. These changes depend on the individual and their particular injury.

Read our article about Sexual Health After SCI for more information!

Complete spinal cord injury

A complete spinal cord injury is when there is a total loss of strength and sensation below the spinal cord injury. This must include complete loss of movement or sensation of the anus (S4 and S5).

In some cases, people with complete injuries may still have some areas of strength or sensation below level of injury (but not including S4 and S5). These areas are known as zones of partial preservation.

Incomplete spinal cord injury

An incomplete spinal cord injury is when some strength and/or sensation remain below the spinal cord injury. This must include some movement or sensation of the anus (S4 and S5).

Incomplete injuries can have very different symptoms depending how much and in what way the injury has affected the spinal cord. These have traditionally been described as different “syndromes”, but more often now are best described by the characteristics of the person’s unique symptoms.

You may hear your healthcare providers use these terms:

| Syndrome | Area of spinal cord injury | Key Symptoms |

| Central cord syndrome | Central areas of the cervical spinal cord |

|

| Brown-Séquard syndrome | One half of the spinal cord (the right or left side) |

|

| Conus medullaris syndrome | The end of the main part of the spinal cord and the start of the ’cauda equina’ |

|

| Cauda equina syndrome | The nerves in lowest part of the spinal canal once the “true” spinal cord has ended |

|

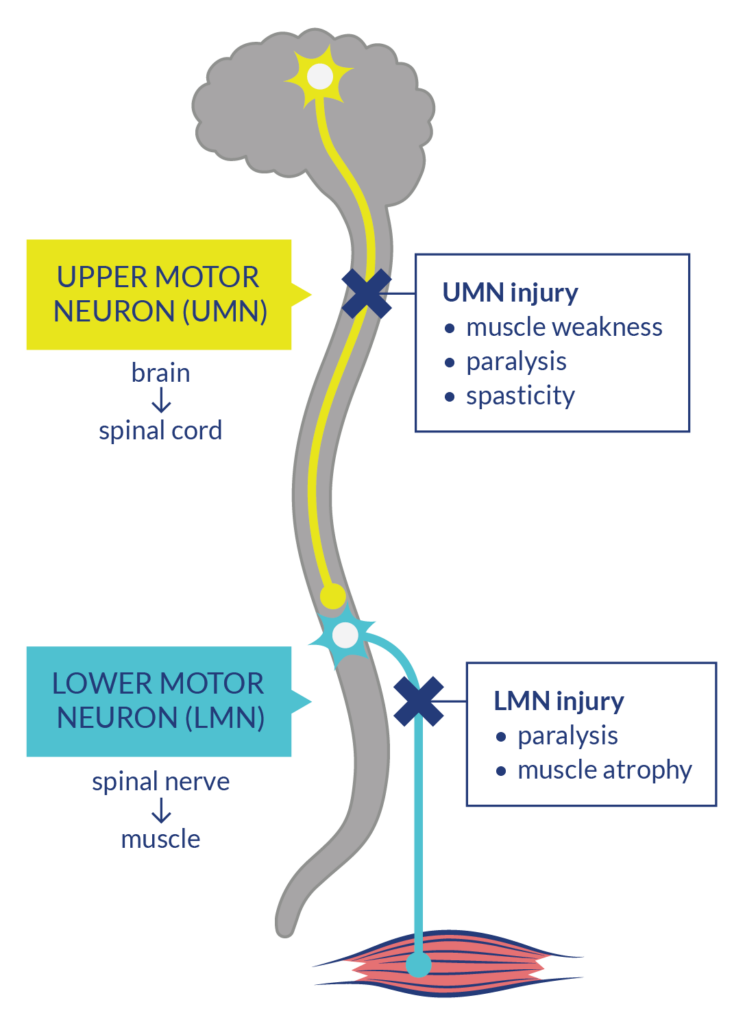

Nerve pathways that send movement commands from the brain to the muscles are made up of two types of neurons: upper motor neurons (UMNs) which start in the brain and go down the spinal cord, and lower motor neurons (LMNs) which connect to the UMN in the spinal and go out to the muscles.

Nerve pathways that send movement commands from the brain to the muscles are made up of two types of neurons: upper motor neurons (UMNs) which start in the brain and go down the spinal cord, and lower motor neurons (LMNs) which connect to the UMN in the spinal and go out to the muscles.

UMN injuries disrupt the neuron connection from the brain to the muscles but keep the spinal reflexes of the LMNs (automatic movement responses to pain or sensation that don’t require signals from the brain), intact. The disruption of brain commands causes muscle weakness/paralysis and leaves the spinal reflexes unmoderated, which presents as spasticity. The uncontrolled activity of spinal reflexes also maintains muscle tone. In contrast, LMN injuries disrupt the neuron connection from both the brain and spinal cord to the muscles. There are no signals going to the muscles at all, which causes muscle paralysis and atrophy (degeneration).

Refer to our article on Spinal Cord Anatomy for more information on motor neurons and spinal reflexes!

The effects of UMN and LMN injuries in SCI can be seen in various systems of the body.

Effects of UMN injury in SCI:

- Spastic neurogenic bladder and/or bowel

- Sexual health – loss of psychogenic arousal (from thoughts) but retain reflex arousal (from touch)

- Spasticity

- Autonomic Dysreflexia

Effects of LMN injury in SCI:

- Flaccid neurogenic bladder and/or bowel

- Sexual health – loss of reflex arousal but retain psychogenic arousal

Refer to our articles on Bladder Changes After SCI, Bowel Changes After SCI, Sexual Health After SCI, Spasticity, and Autonomic Dysreflexia for more information!

Mixed UMN and LMN injuries

Depending on their injury, a person with SCI could be more likely to have UMN, LMN, or both injuries at the same time. For example, a cauda equina injury happens at the bottom of the spinal cord where all the nerves are LMNs, while a conus medullaris injury is likely to be a mix of both. Injuries caused by trauma will often injure both the UMNs at the spinal cord and surrounding LMNs.

Relevance to treatment

The advancement of treatments like nerve transfer and functional electrical stimulation that depend on intact LMN function bring attention to the need to distinguish UMN from LMN injury. Determining if one has an UMN or LMN injury is accomplished by diagnostic techniques such as nerve conduction studies and electromyography.

Refer to our articles on Nerve Transfer Surgery and Functional Electrical Stimulation for more information!

Neurological level of injury is the lowest level of the spinal cord that has normal function, which is confirmed using strength and sensation tests. Level of injury is an important classification that, together with whether the injury is complete or incomplete, can be used to describe how much physical function a person is likely to have.

What are tetraplegia (quadriplegia) and paraplegia?

Although not specifically describing level of injury, tetraplegia and paraplegia are terms used to describe the extent of a spinal cord injury’s effects on the body.

Although not specifically describing level of injury, tetraplegia and paraplegia are terms used to describe the extent of a spinal cord injury’s effects on the body.

Tetraplegia, or Quadriplegia, describes injuries that affect the cervical spinal cord and causes a partial or total loss of strength and sensation of the neck, trunk, arms and legs (all four limbs).

Paraplegia describes injuries that affect the thoracic, lumbar or sacral spinal cord and causes a partial or total loss of strength and sensation of the legs and trunk, without affecting the arms.

The International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (ISNCSCI) exam (often called the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) exam) is a physical exam that is used to classify spinal cord injuries. It determines both the neurological level of injury and the completeness of the injury.

During this exam, a health provider such as a doctor or physiotherapist will carefully test for sensation and strength at specific points on the body and use the exam findings to determine the characteristics of the injury. These tests include:

- Testing for “light touch” sensation (if you can feel the touch of a cotton swab or tissue and whether it feels normal)

- Testing for “pin prick” sensation (if you can feel whether the touch of a safety pin is sharp or dull and whether it feels normal)

- Testing for muscle strength of specific muscles (if you can resist against certain movements applied by the health provider)

- Testing for movement and sensation of the anus. This is a very important test because it is the only way we can determine if a person’s injury is complete or incomplete). It is testing the last nerves to leave the spinal cord (S4 and S5).

ASIA Impairment Scale (AIS)

The ASIA Impairment Scale (AIS) describes the completeness of the injury. This scale identifies whether a person has any movement or sensation in the lowest levels of the spinal cord (S4 and 5) and what movement or sensation they have below the neurological level of injury. If you are interested in learning how healthcare providers are trained to do the test, you can visit: scireproject.com/outcome/ais/.

| A, Complete | No sensation or movement below the injury, including around the anus (S4 and 5) |

| B, Sensory Incomplete | There is sensation, but not movement below the injury, including around the anus (S4 and 5) |

| C, Motor Incomplete | There is movement, but not sensation below the level of injury and more than half of the muscles below the injury are quite weak |

| D, Motor Incomplete | Movement is present below the injury and at least half of muscles below the injury have close to normal strength |

| E, Normal | Sensation and movement are normal |

Spinal cord injury is a relatively rare condition. Although estimates vary by country and study, it is estimated 86,000 people were living with SCI in Canada in 2010. New injuries were estimated to be 4,300 per year in 2010.

It is best to discuss all treatment options with your health providers to find out which treatments are suitable for you.

For a review of how we assess evidence at SCIRE Community and advice on making decisions, please see SCIRE Community Evidence.

Eng JJ (2014). Rehab: From Bedside to Community. In Eng JJ, Teasell RW, Miller WC, Wolfe DL, Townson AF, Hsieh JTC, Connolly SJ, Noonan VK, Loh E, McIntyre A, editors. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence. Version 5.0. Vancouver: p. 1-48.

Furlan JC, Krassioukov A, Miller WC, Trenaman LM (2014). Epidemiology of Traumatic Spinal cord Injury. In Eng JJ, Teasell RW, Miller WC, Wolfe DL, Townson AF, Hsieh JTC, Connolly SJ, Noonan VK, Loh E, McIntyre A, editors. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence. Version 5.0. Vancouver: p 1- 121.

Available from: scireproject.com/evidence/epidemiology-of-traumatic-sci/

Brodell DW, Jain A, Elfar JC, Mesfin A. National trends in the management of central cord syndrome: an analysis of 16,134 patients. Spine J. 2015 Mar 1;15(3):435-42. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.09.015. Epub 2014 Sep 28.

Van Middendorp JJ, Goss B, Urquhart S, Atresh S, Williams RP, Schuetz M. Diagnosis and Prognosis of Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury. Global Spine Journal. 2011;1(1):1-8. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1296049.

Kirshblum SC, Burns SP, Biering-Sorensen F, Donovan W, Graves DE, Jha A, Johansen M, Jones L, Krassioukov A, Mulcahey MJ, Schmidt-Read M, Waring W. International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury (revised 2011). J Spinal Cord Med. 2011 Nov;34(6):535-46. doi: 10.1179/204577211X13207446293695.

American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Learning Center. International Standards for Neurological Classification of spinal cord injury (ISNCSCI). Available from: http://lms3.learnshare.com/Images/Brand/120/ASIA/International%20Standards%20Worksheet.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2016.

Noonan VK, Fingas M, Farry A, Baxter D, Singh A, Fehlings MG, Dvorak MF. Incidence and prevalence of spinal cord injury in Canada: a national perspective. Neuroepidemiology. 2012;38(4):219-26.

New PW, Cripps RA, Bonne Lee B.Global maps of non-traumatic spinal cord injury epidemiology: towards a living data repository. Spinal Cord. 2014 Feb;52(2):97-109.

Farry A, Baxter D. The Incidence and Prevalence of Spinal Cord Injury in Canada: Overview and estimates based on current evidence. Rick Hansen Institute and Urban Futures Institute 2010.

McCammon JR, Ethans K. J Spinal Cord Med. 2011;34(1):6-10. Spinal cord injury in Manitoba: a provincial epidemiological study.

Warren S, Moore M, Johnson MS. Traumatic head and spinal cord injuries in Alaska (1991-1993). Alaska Med. 1995 Jan-Mar;37(1):11-9.

Evidence for “What are “upper” and “lower” motor neurons?”

Emos MC, Agarwal S. Neuroanatomy, Upper Motor Neuron Lesion. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

Javed K, Daly DT. Neuroanatomy, Lower Motor Neuron Lesion. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

Zayia LC, Tadi P. Neuroanatomy, Motor Neuron. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

Doherty JG, Burns AS, O’Ferrall DM, Ditunno JF. Prevalence Of Upper Motor Neuron Vs Lower Motor Neuron Lesions In Complete Lower Thoracic And Lumbar Spinal Cord Injuries. J Spinal Cord Med. 2002 Dec;25(4):289–92.

Kingwell SP, Curt A, Dvorak MF. Factors affecting neurological outcome in traumatic conus medullaris and cauda equina injuries. Neurosurg Focus. 2008 Nov;25(5):E7.

Bryden AM, Hoyen HA, Keith MW, Mejia M, Kilgore KL, Nemunaitis GA. Upper Extremity Assessment in Tetraplegia: The Importance of Differentiating Between Upper and Lower Motor Neuron Paralysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016 Jun;97(6):S97–104.

Mulcahey MJ, Smith B, Betz R. Evaluation of the lower motor neuron integrity of upper extremity muscles in high level spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 1999 Aug 9;37(8):585–91.

Image credits

- SCIRE “I” by SCIRE

- Image by SCIRE

- Blood Pressure ©Alexander Panasovsky, CC BY 3.0 US

- Dermatoms © Ralf Stephan, CC0 1.0

- Image by SCIRE

- Excretory system ©Olena Panasovska, CC BY 3.0 US

- Image by SCIRE

- Arm ©Jacqueline Fernandes, CC BY 3.0 US

- Leg ©Bakunetsu Kaito. CC BY 3.0 US

- Image by SCIRE